Interesting Cases

December 2024: Chemotherapy Toxicity

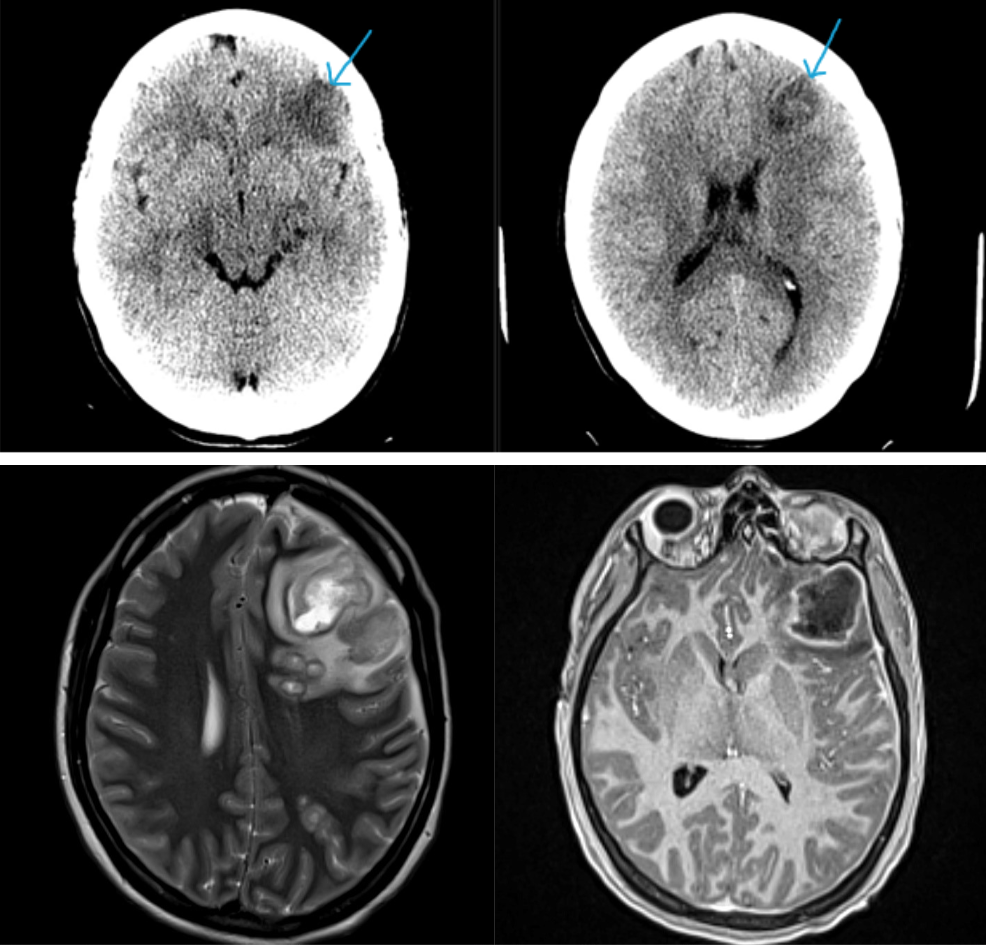

History: A female patient presented to the emergency department with her family for progressive confusion. She had a history of pelvic malignancy which was currently being treated with chemotherapy. There were no focal neurologic deficits on physical exam. Imaging of the brain was ordered.

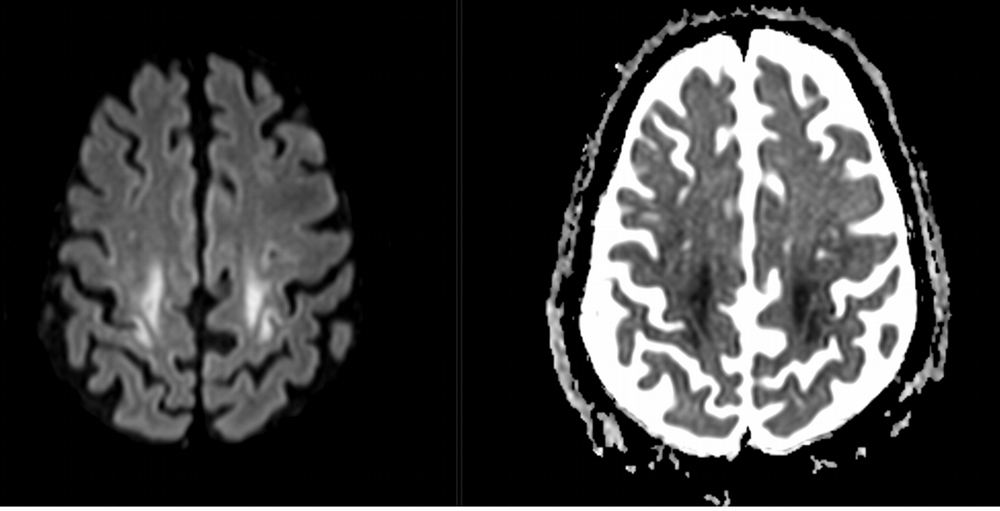

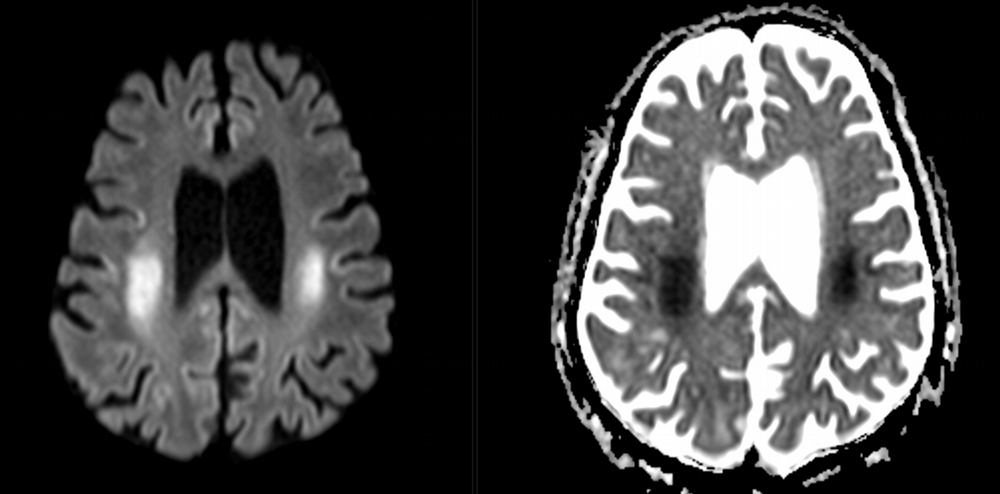

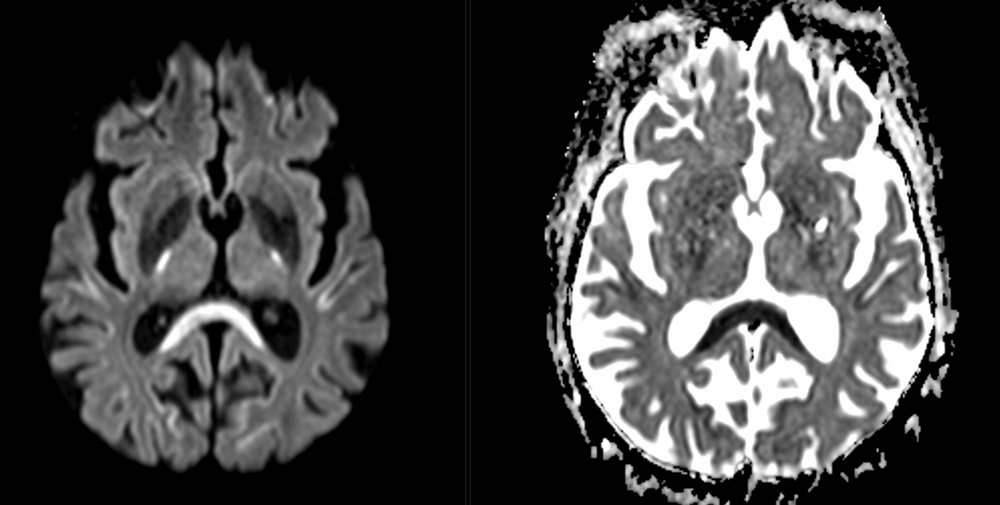

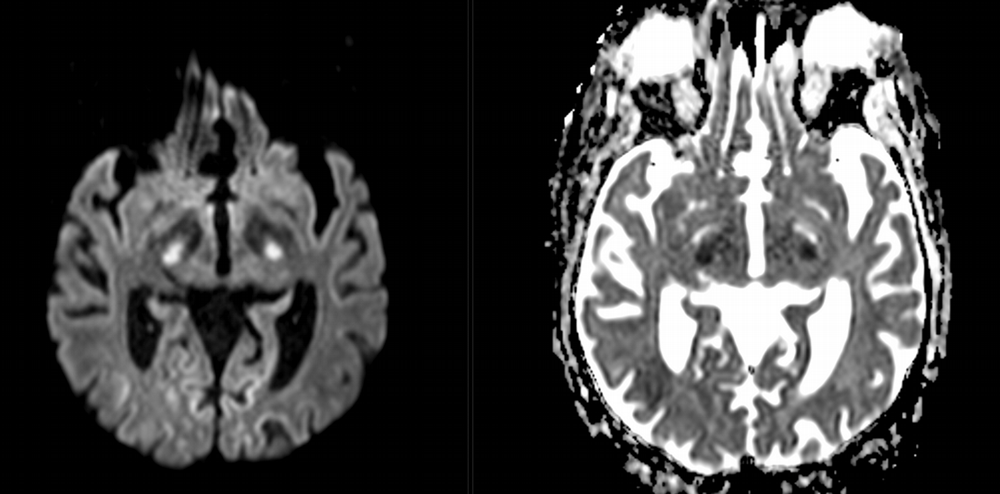

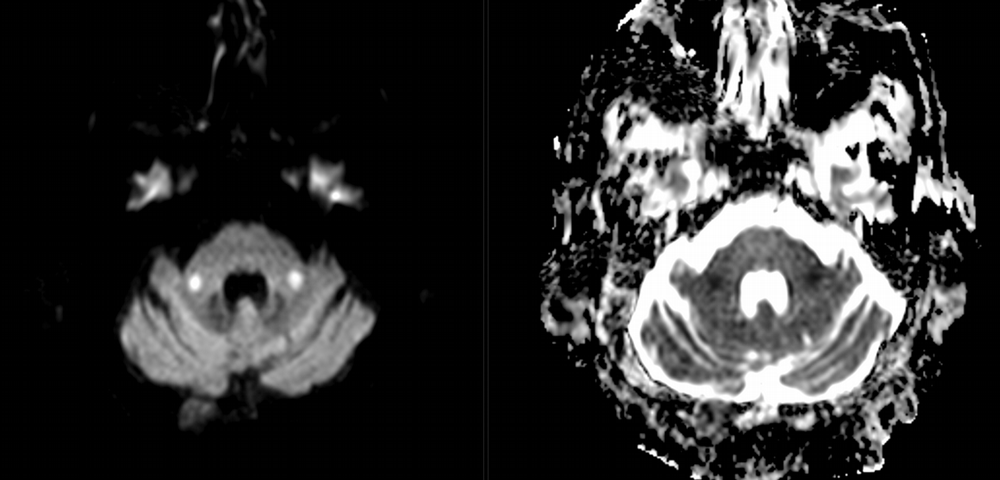

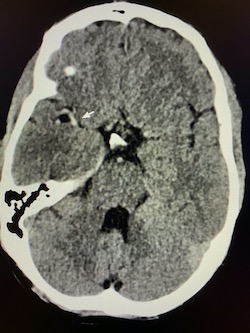

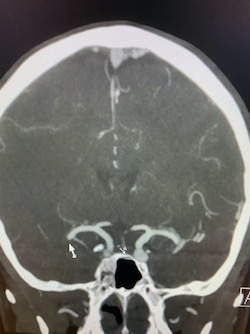

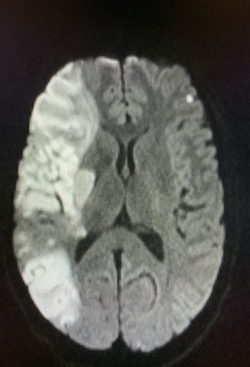

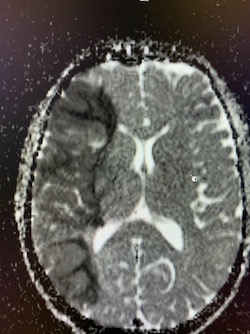

Imaging Findings: Noncontrast CT of the brain (not shown) was unremarkable. The isotropic diffusion weighted sequence (screen left) and corresponding apparent diffusion coefficient map (screen right) reveal symmetric diffusion restriction involving the white matter of the bilateral centrum semiovale, corona radiata, basal ganglia, splenium of the corpus callosum, and middle cerebral peduncles. There was no enhancement or gradient susceptibility associated with this signal abnormality.

Diagnosis: Toxic leukoencephalopathy

Course: The MR findings were suggestive of a metabolic or toxic encephalopathy, which can be seen with chemotherapy agents. The oncology service attributed this to the patient’s chemotherapy regimen, specifically the use of 5-fluorouracil which was subsequently discontinued. Vistogard (uridine triacetate) is a 5-FU antidote and was prescribed. The patient’s encephalopathy resolved shortly thereafter. Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase genotyping was performed which revealed a mutation resulting in impaired metabolism of 5-FU.

Discussion: Diffusion weighted imaging is classically associated with detection of ischemic stroke. Symmetric patterns of diffusion restriction such as in this case should prompt consideration of other pathologies, such as toxic or metabolic encephalopathy. A variety of agents including chemotherapy medications, illicit drugs, environmental toxins such as carbon monoxide, and metabolites such as ammonia can result in this pattern of diffusion restriction. Prompt discontinuation of the offending agent offers the best chance at recovery.

Previous Cases

November 2024: Traumatic Bowel Injury

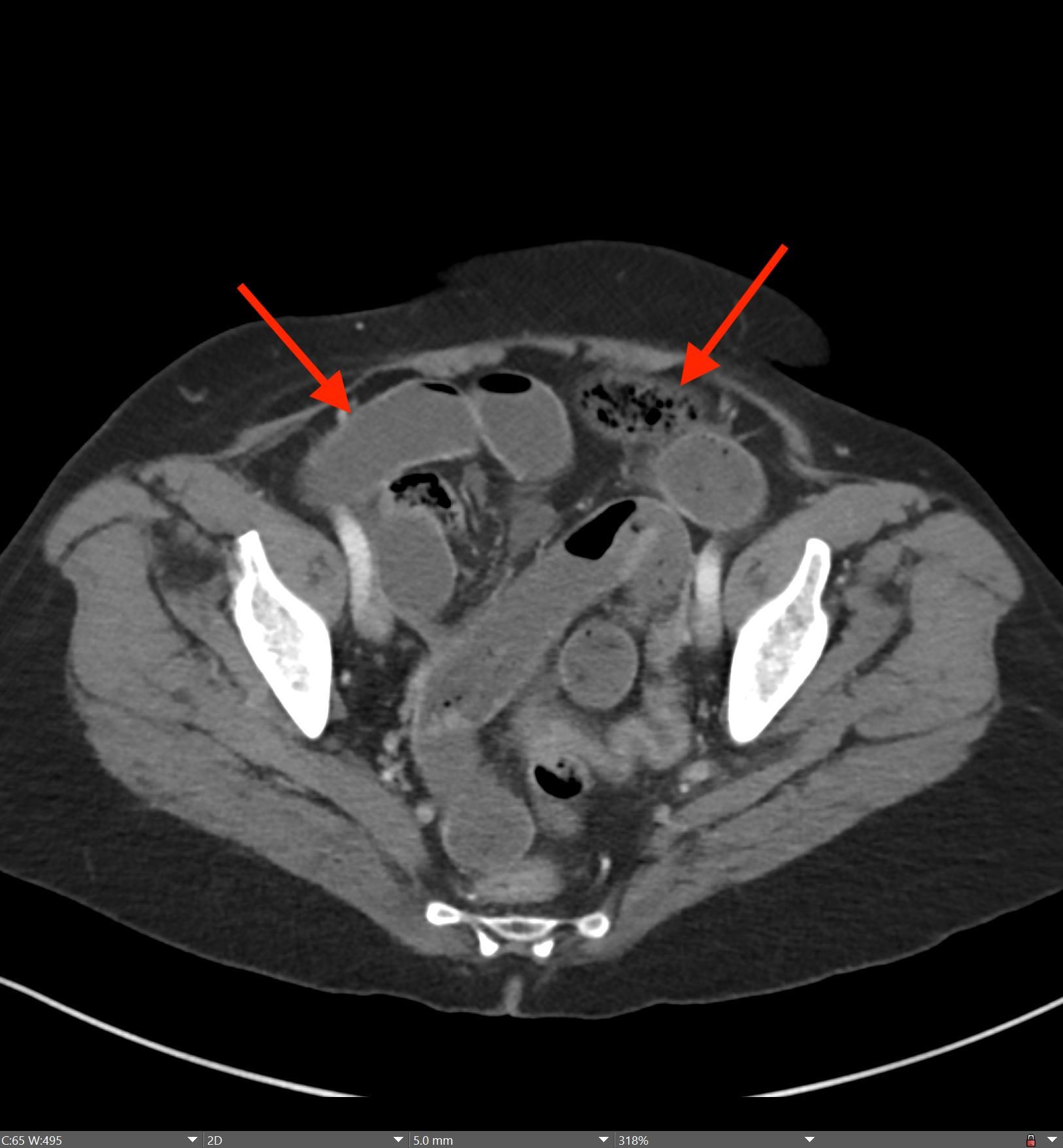

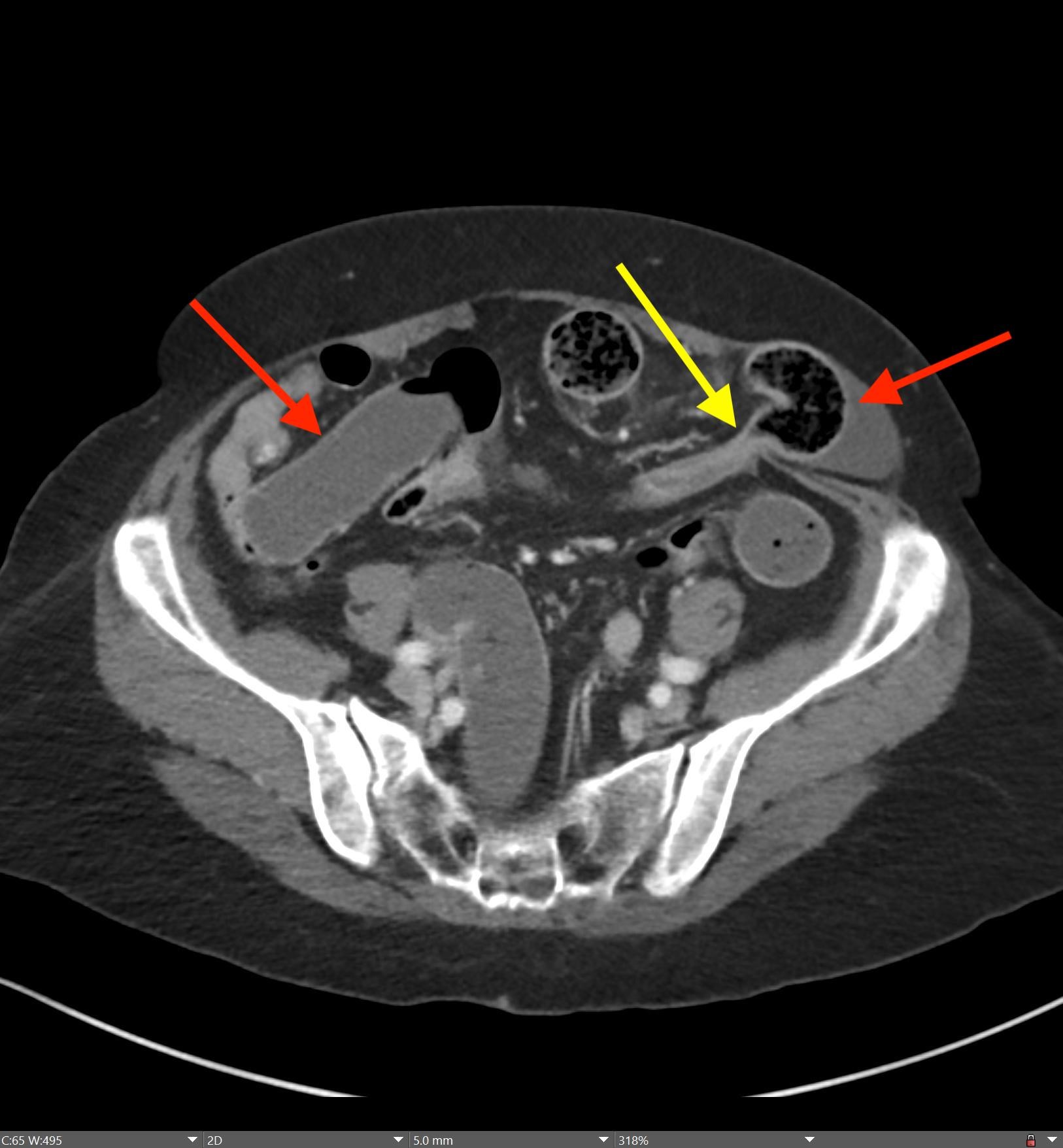

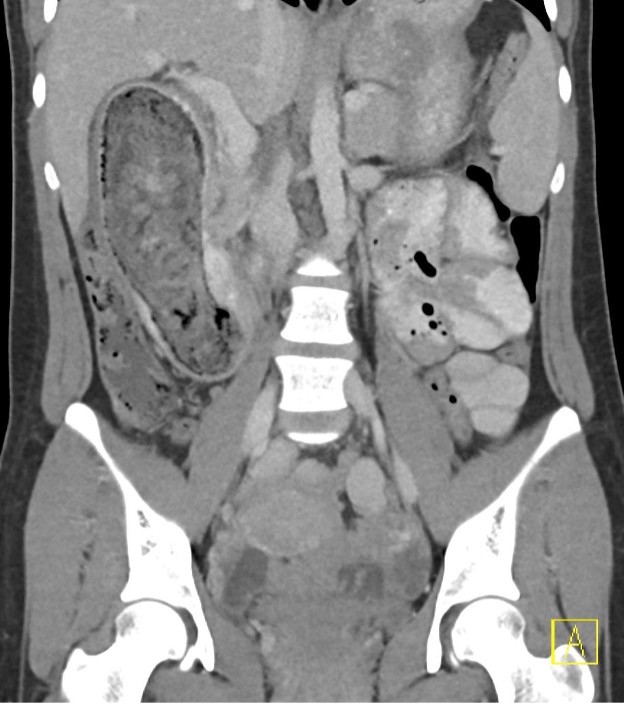

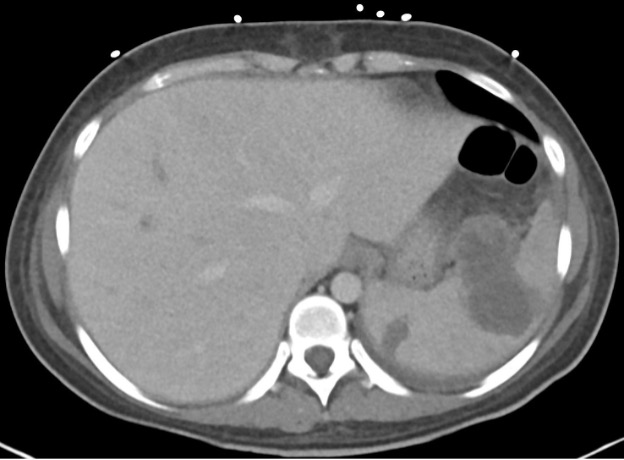

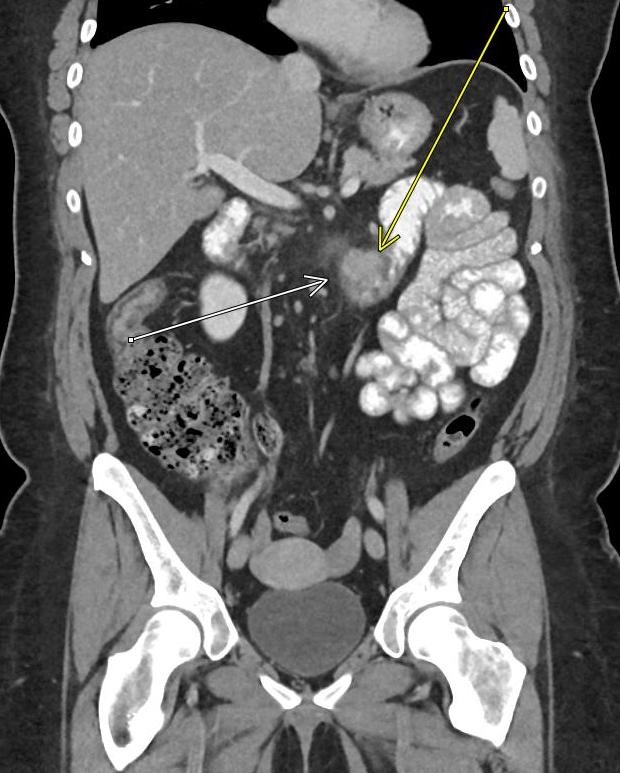

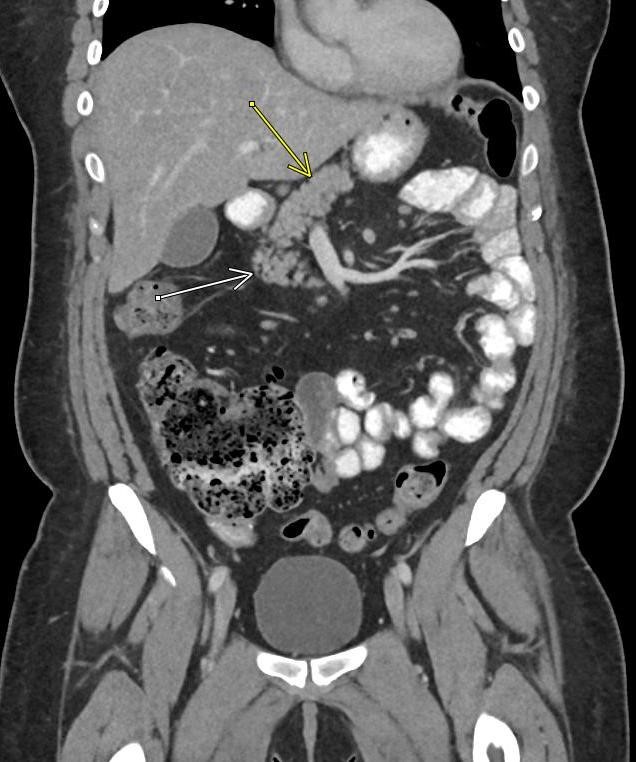

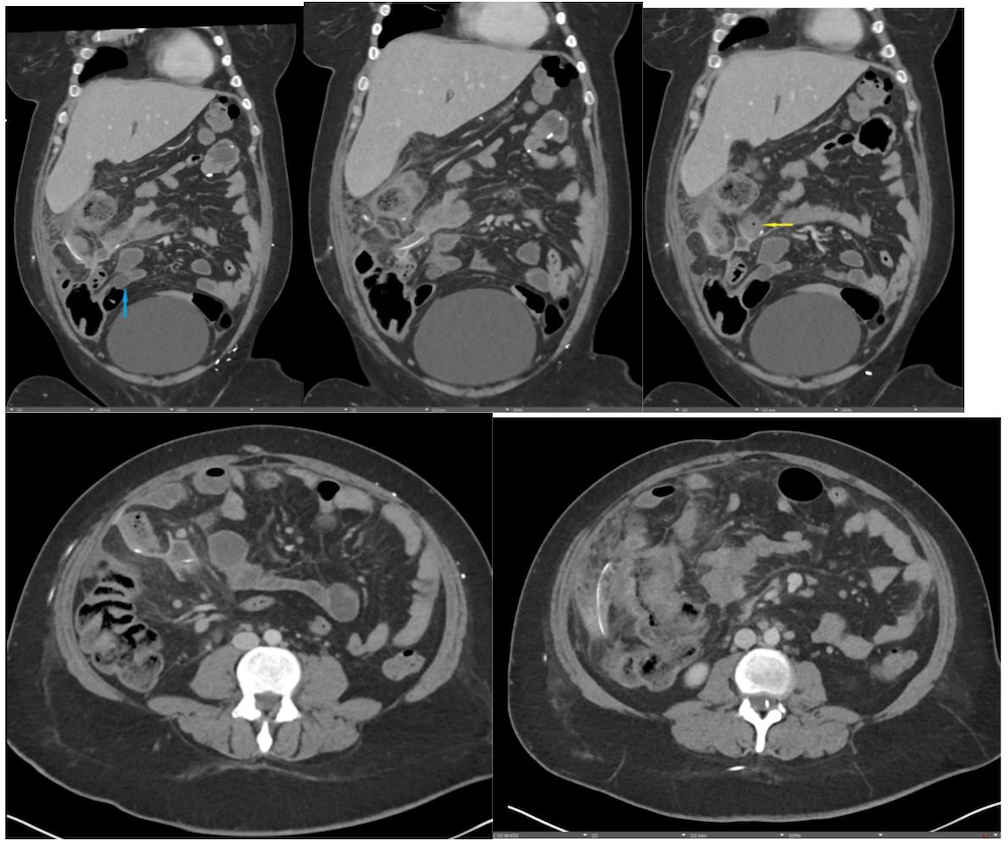

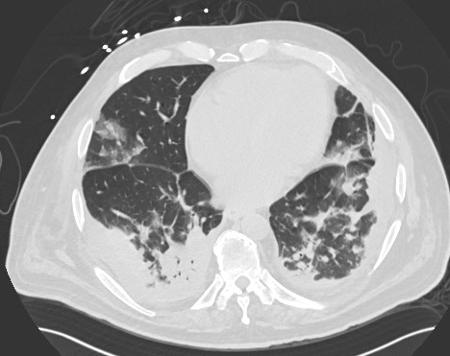

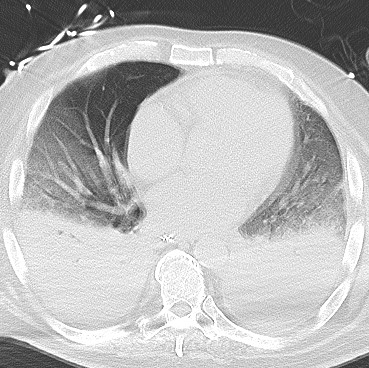

History: A young adult is brought to the emergency department by EMS after a high-speed motor vehicle collision. Physical exam was notable for a seatbelt sign with diffuse abdominal tenderness. Cross-sectional imaging was performed after the initial trauma survey.

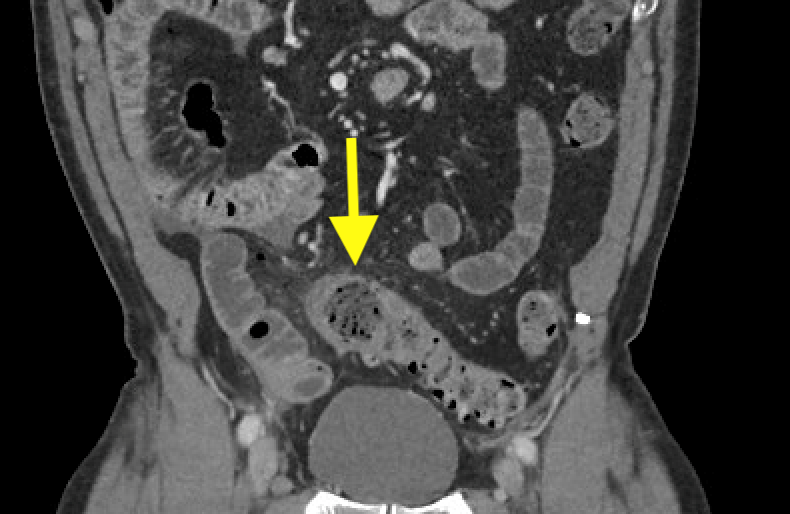

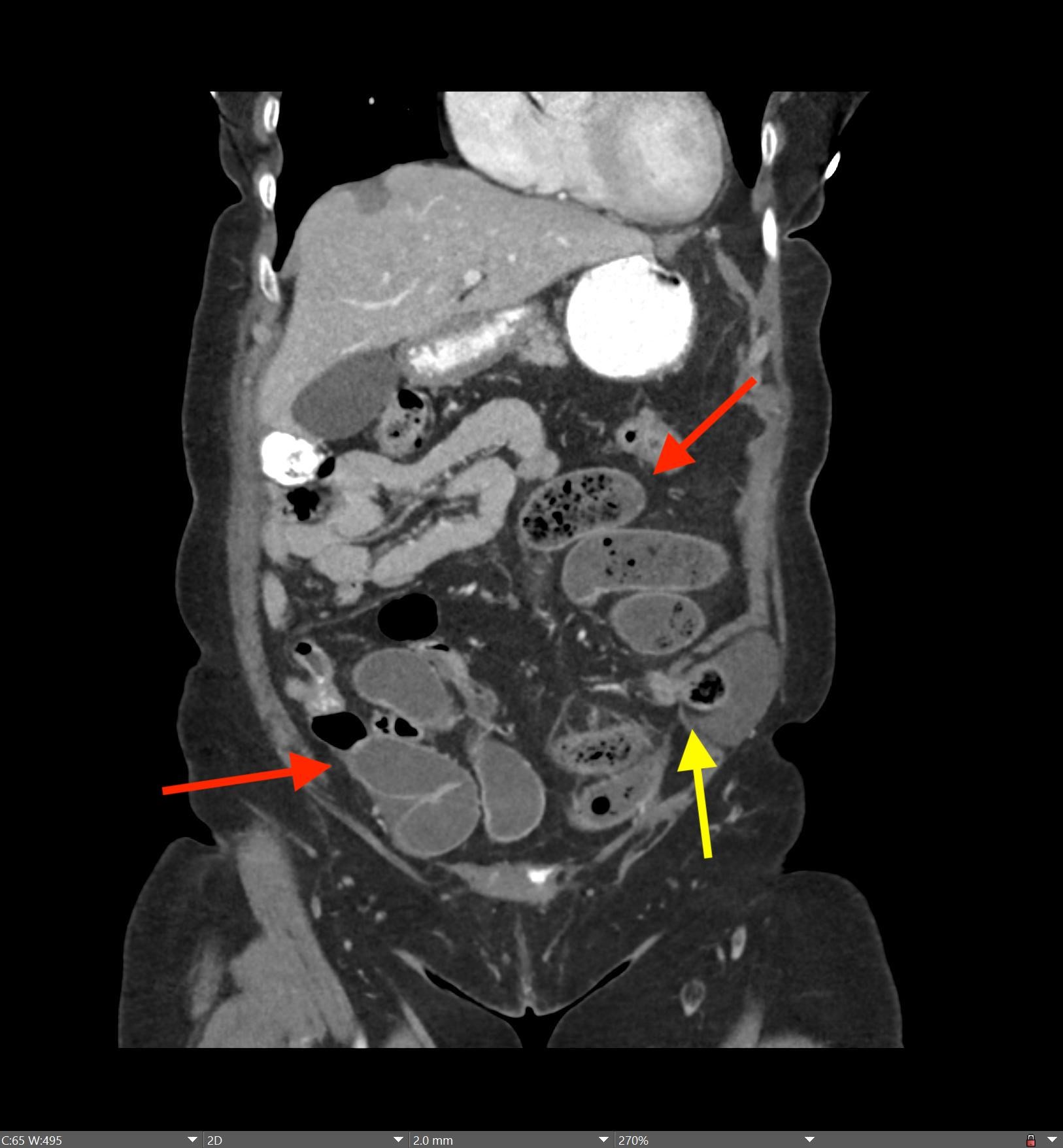

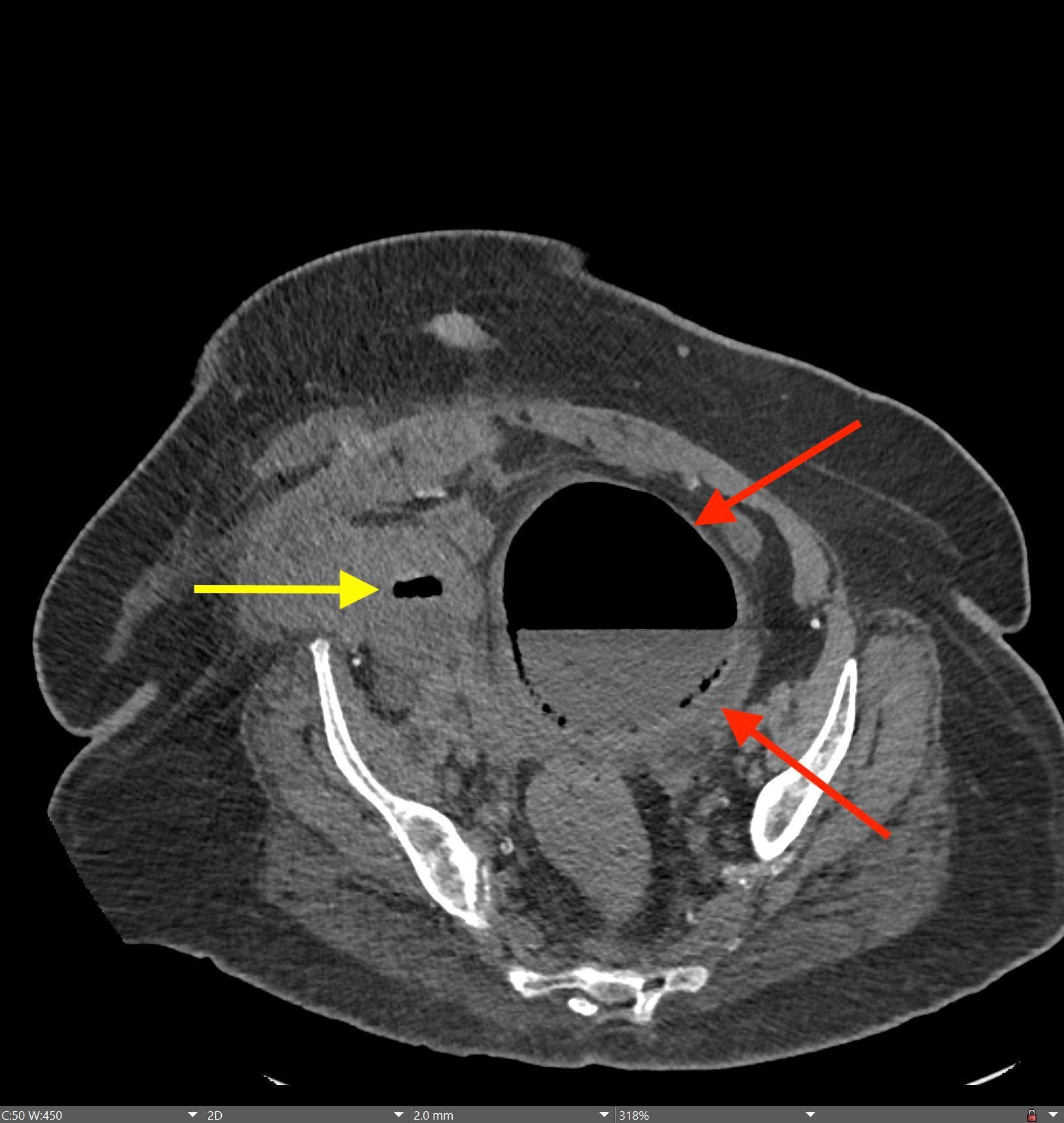

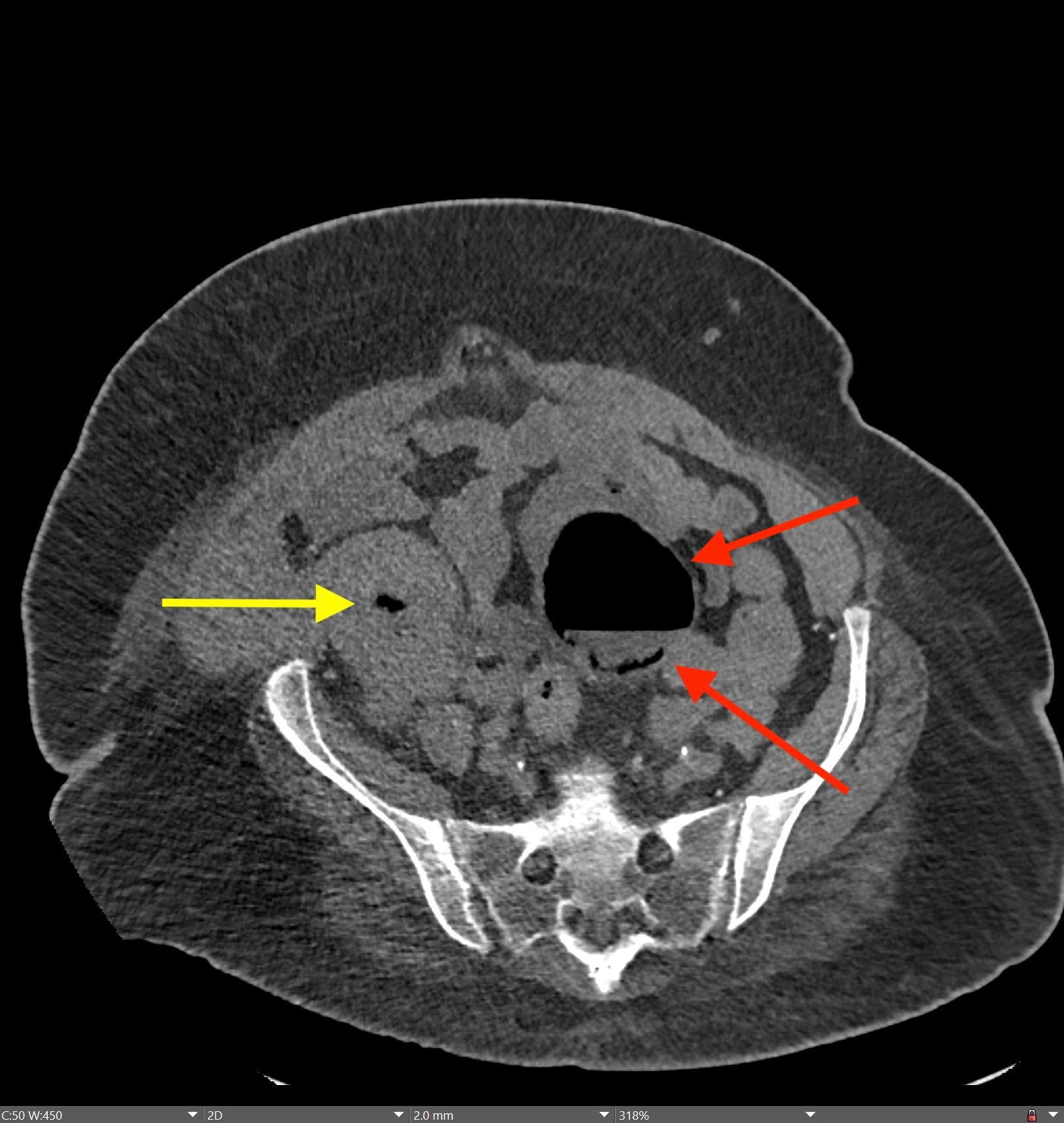

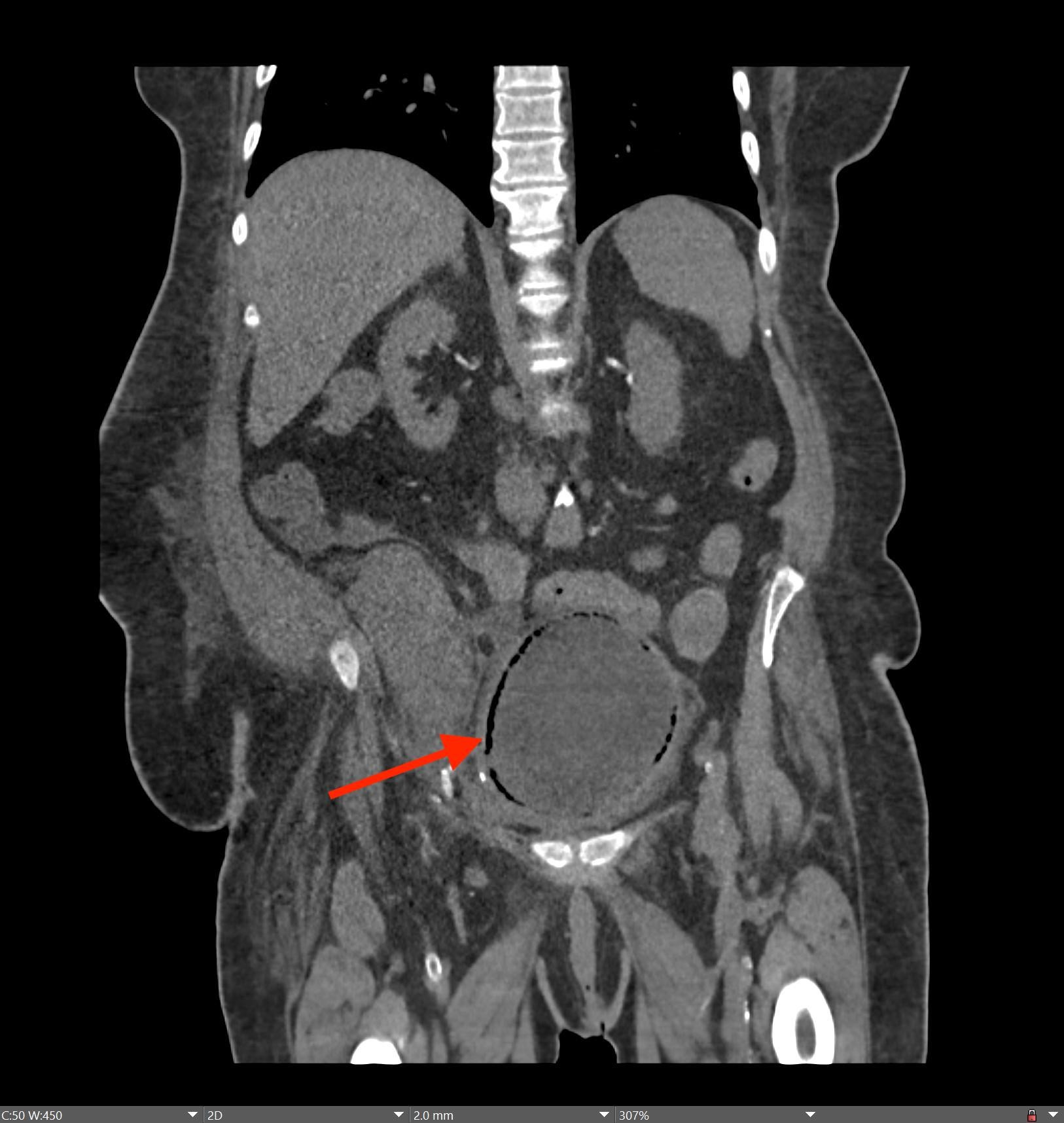

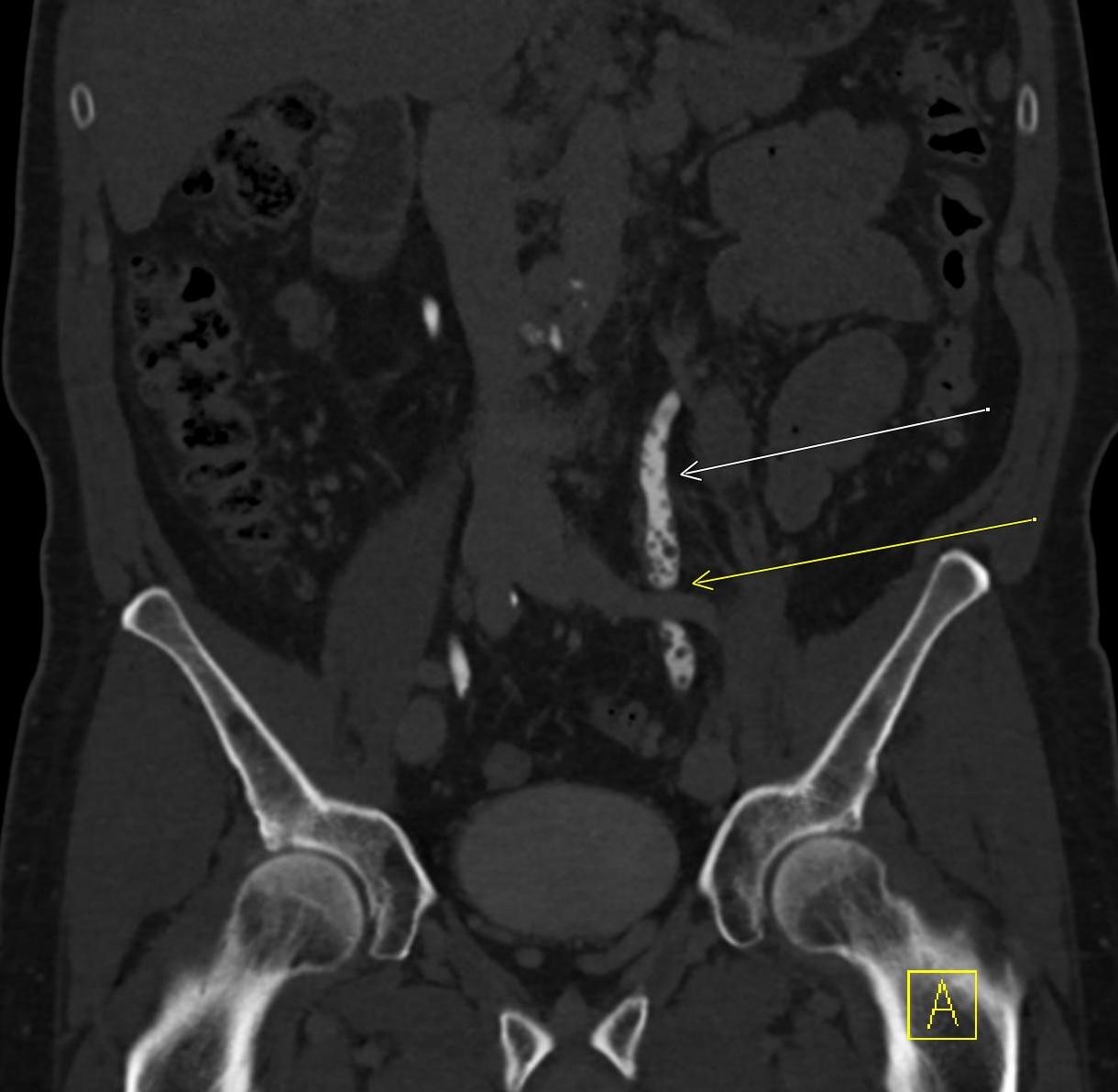

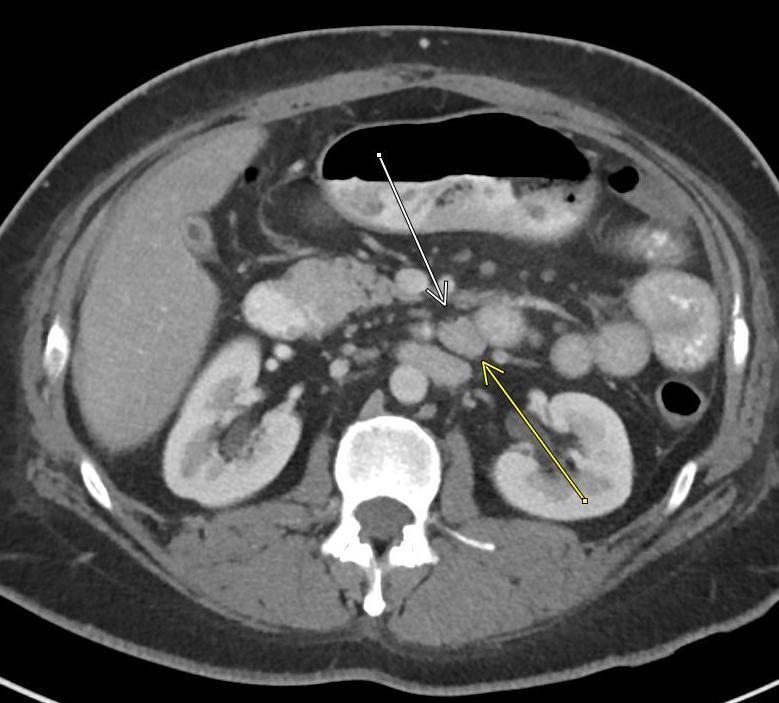

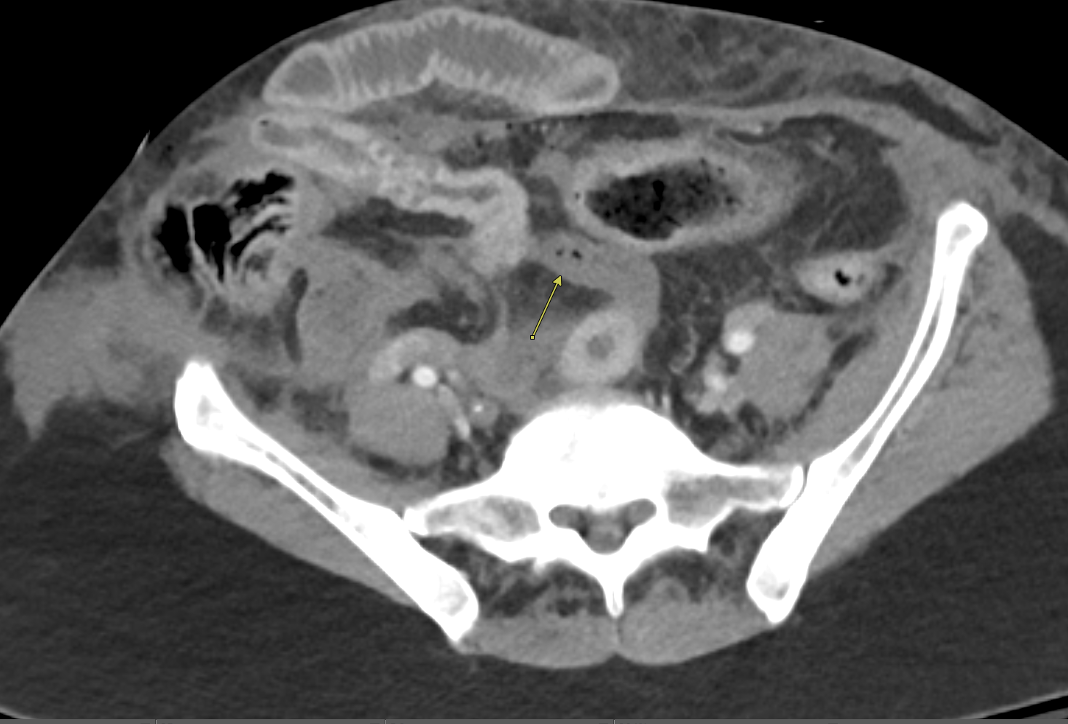

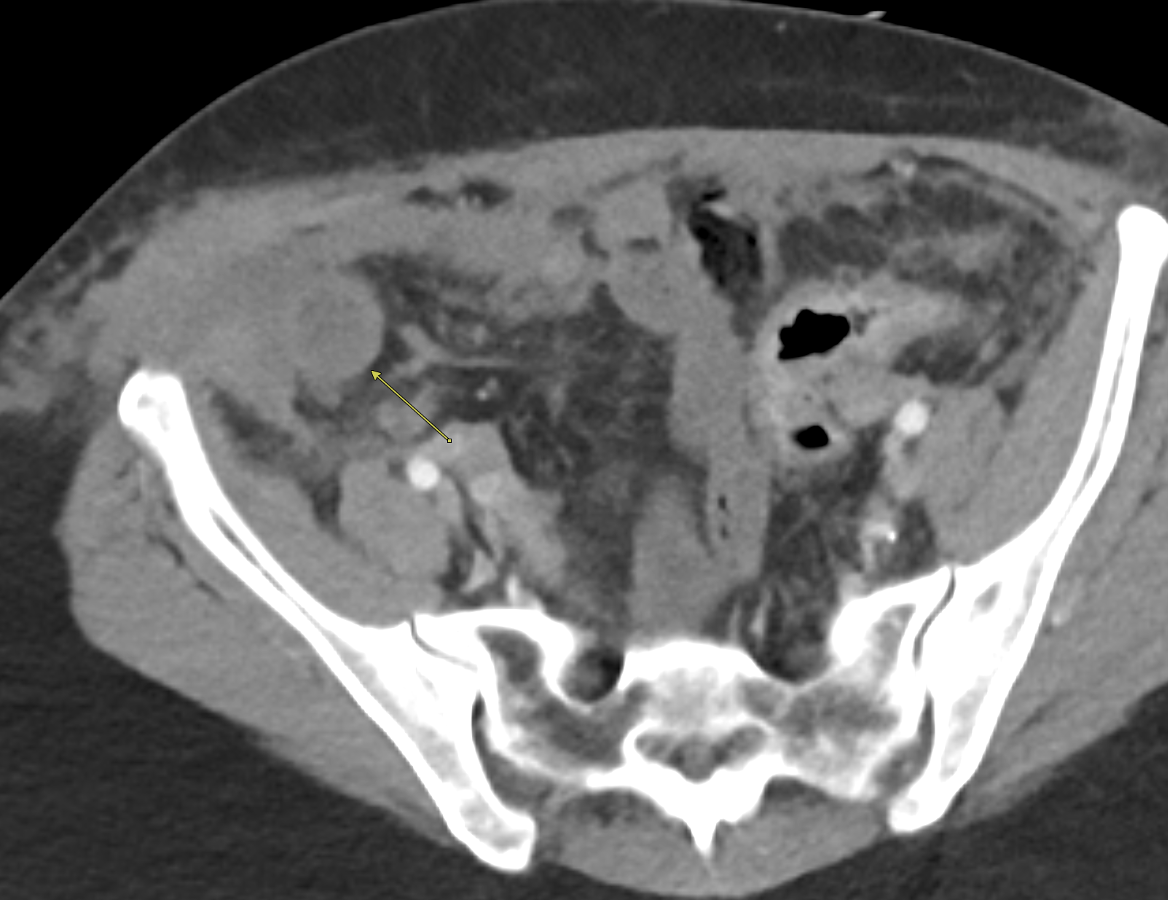

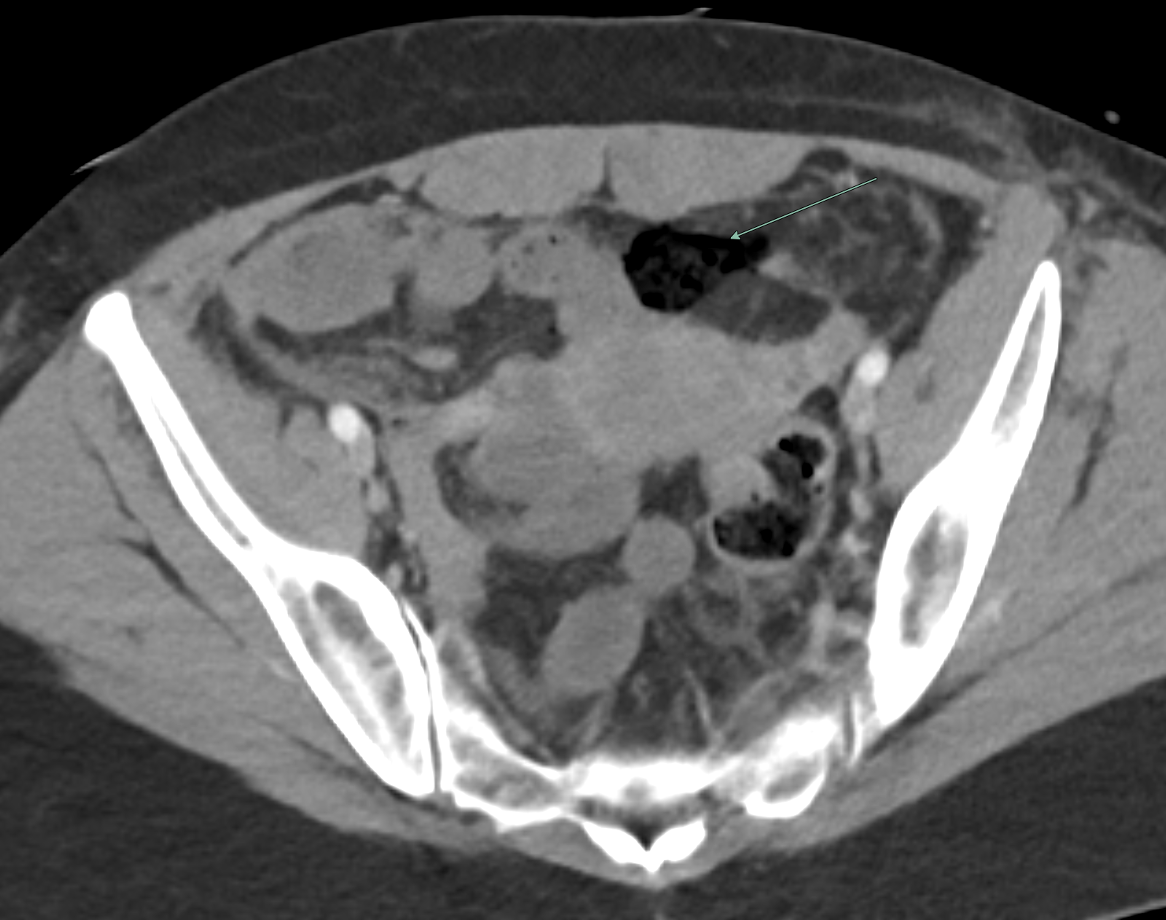

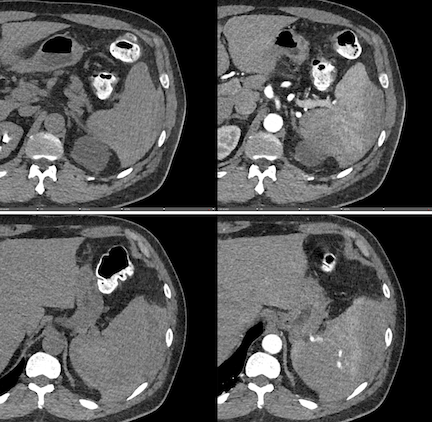

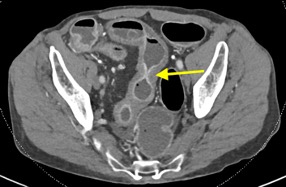

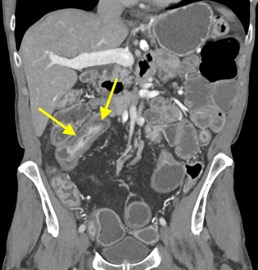

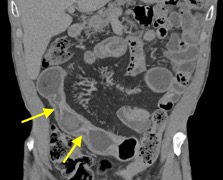

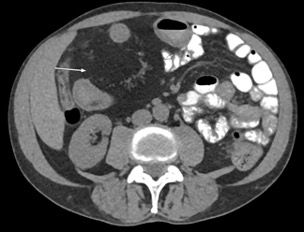

Imaging Findings: Contrast enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis reveals multiple loops of hypoenhancing small bowel in the lower abdomen compatible with traumatic devascularization. There is contusion in the flanks and anterior abdominal wall. There is free fluid surrounding several loops of small bowel providing additional evidence of traumatic bowel injury. There is extraluminal fecal material adjacent to a focal discontinuity in the wall of the transverse colon compatible with traumatic colonic perforation.

Diagnosis: Traumatic small bowel devascularization and transverse colon perforation.

Course: The patient was taken emergently to the operating room for exploratory laparotomy. Blood clots and stool were present upon entry into the abdomen. There were multiple small bowel mesentery bucket handle tears with ischemic loops of jejunum and ileum. There was an ischemic and perforated segment of the mid transverse colon. Abdominal washout and resection of injured small bowel and colon was performed with formation of a diverting ostomy. The patient had a lengthy post-operative course but survived.

Discussion: Evidence of traumatic bowel injury on imaging almost always necessitates operative exploration. Blunt trauma can result in shear injuries at sites of bowel fixation, such as the ligament of Treitz or adhesions in patients with prior abdominal surgeries. Blunt trauma can also result in crush injuries as the bowel is compressed between the spine/pelvic bones and external objects such as a bike handlebar or steering wheel. Small bowel is more commonly injured than large bowel in the setting of blunt trauma. The presence of a seatbelt sign on exam significantly raises probability bowel injury. Patients with severe abdominal injuries are typically left with an open abdomen and will be taken back to the OR for definitive management after resuscitation and medical stabilization in the intensive care unit.

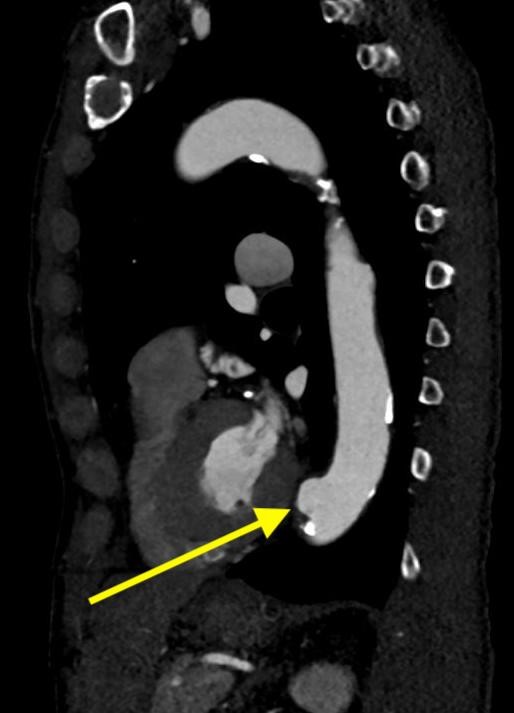

October 2024: Traumatic Aortic Injury

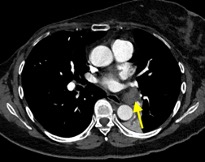

History: A young adult male is brought to the emergency department by EMS after a motorcycle accident. The patient was sedated and intubated in the field. The patient was hemodynamically stable upon arrival and then taken for cross-sectional imaging after the initial trauma survey.

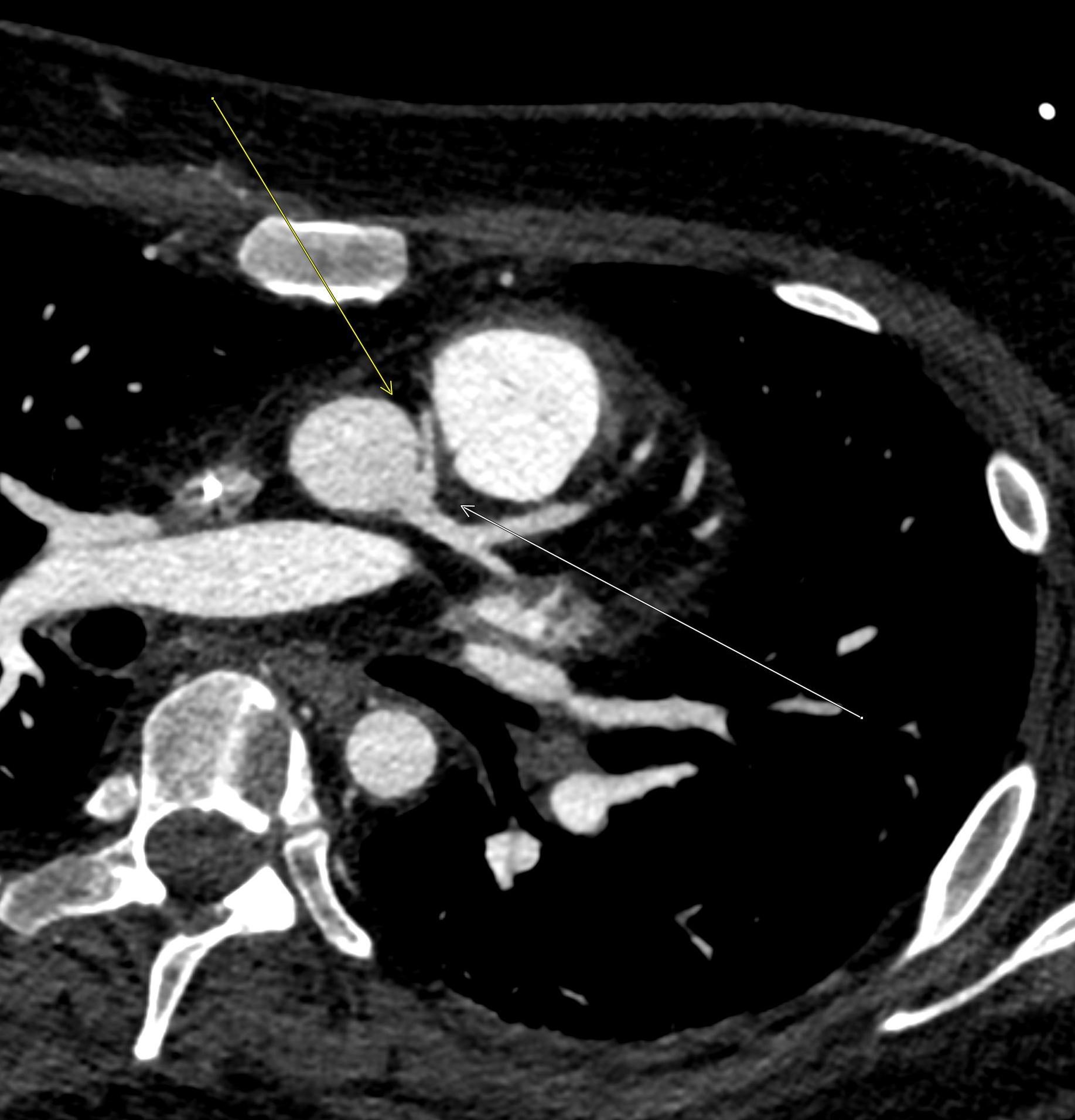

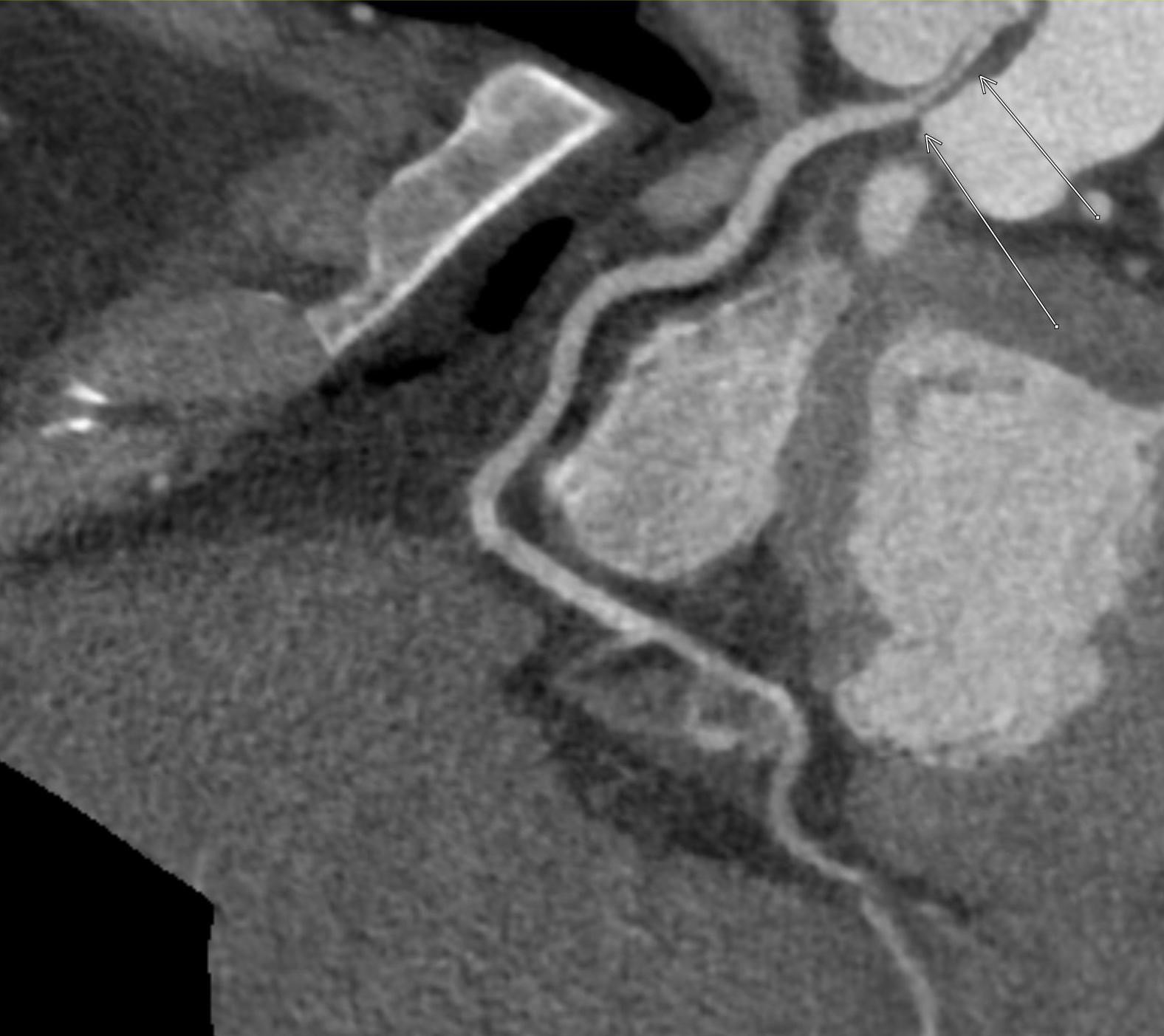

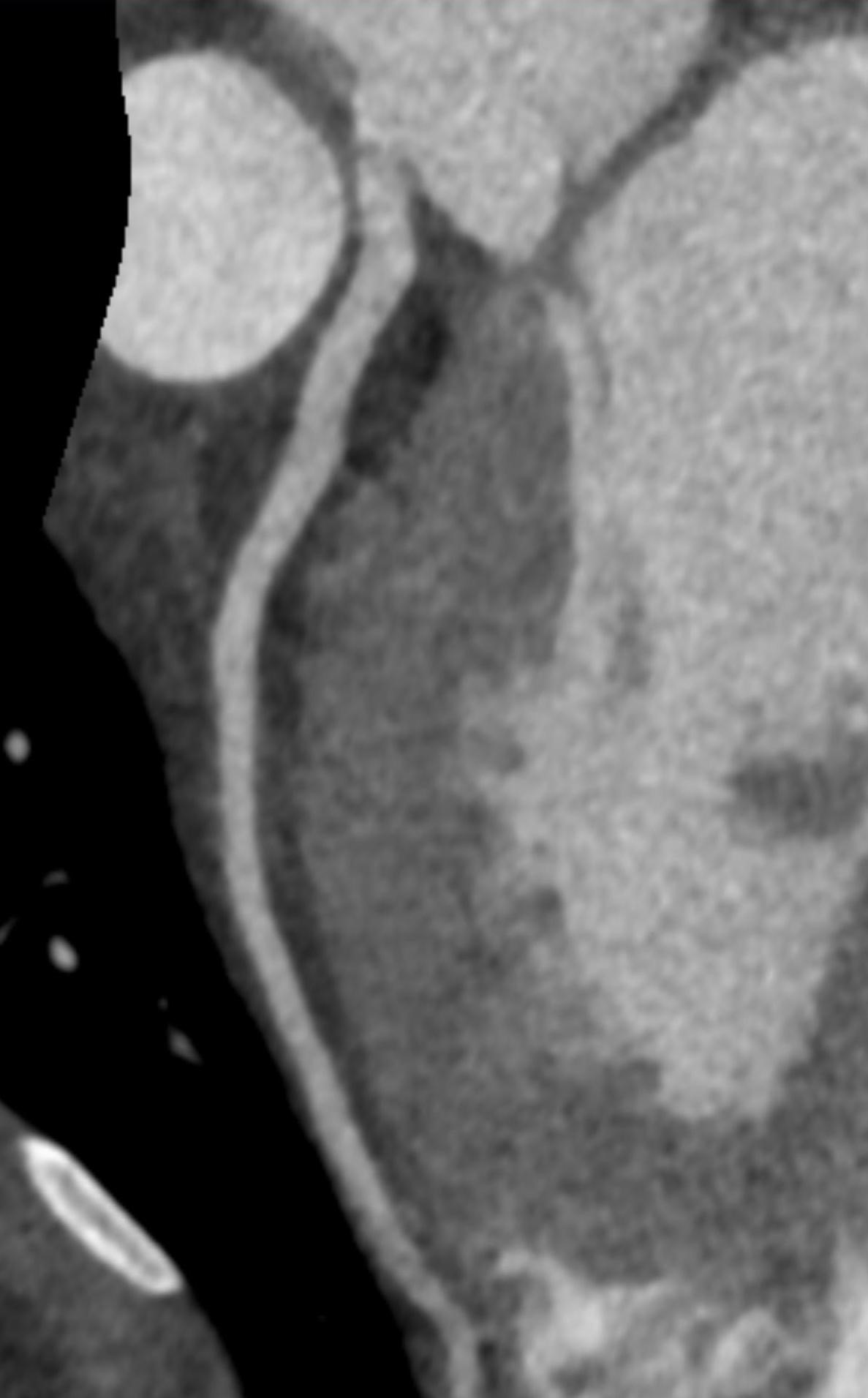

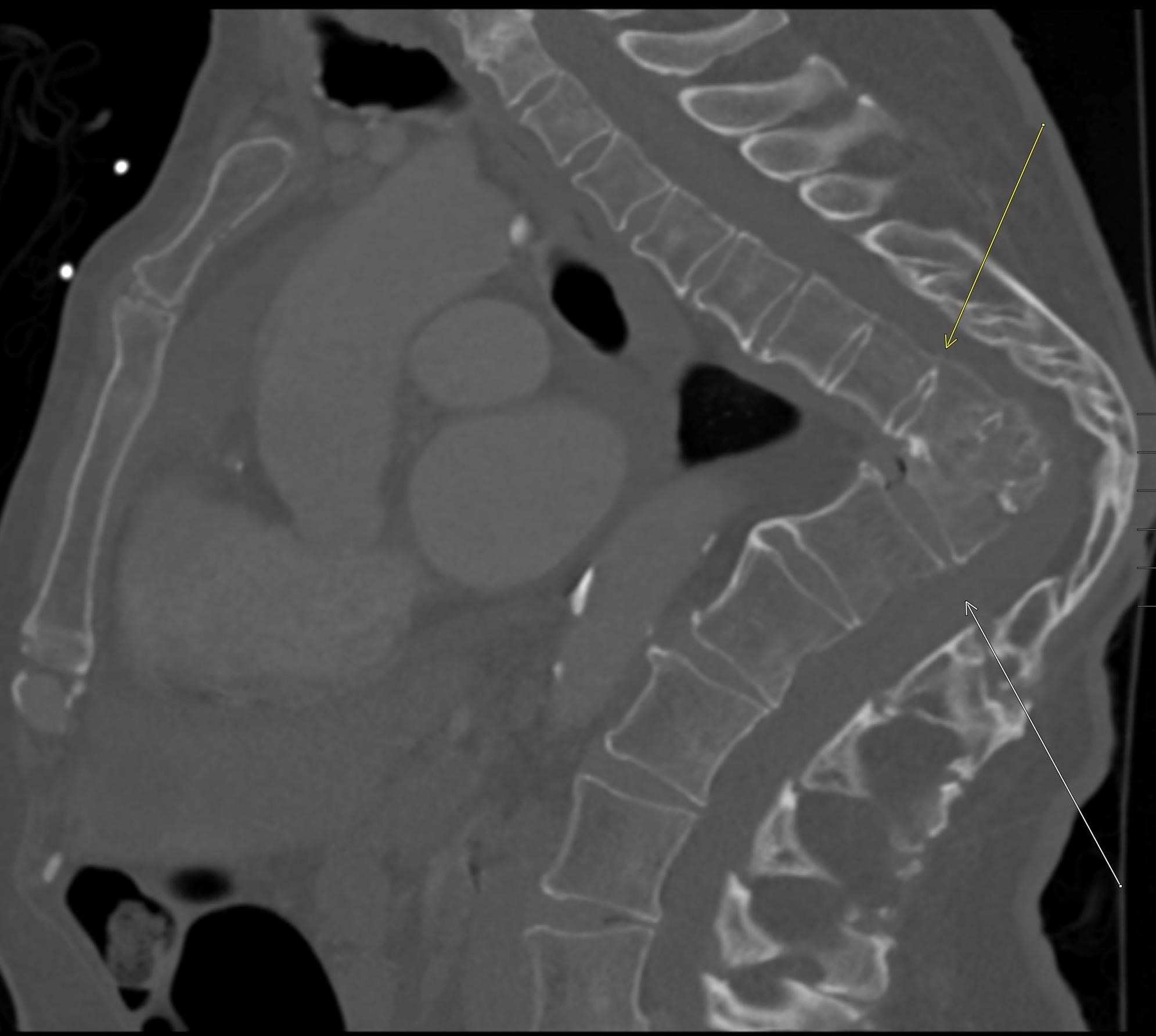

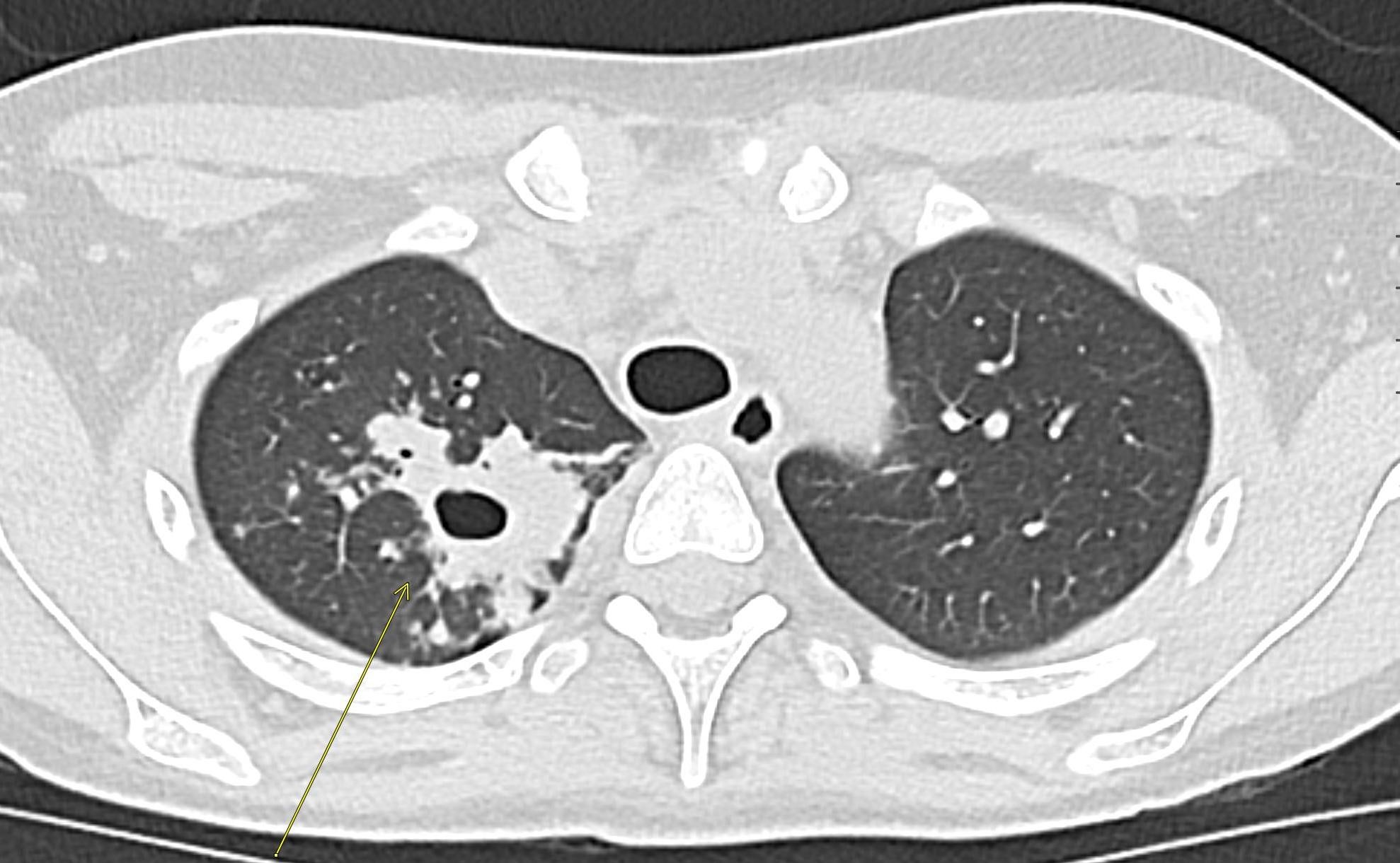

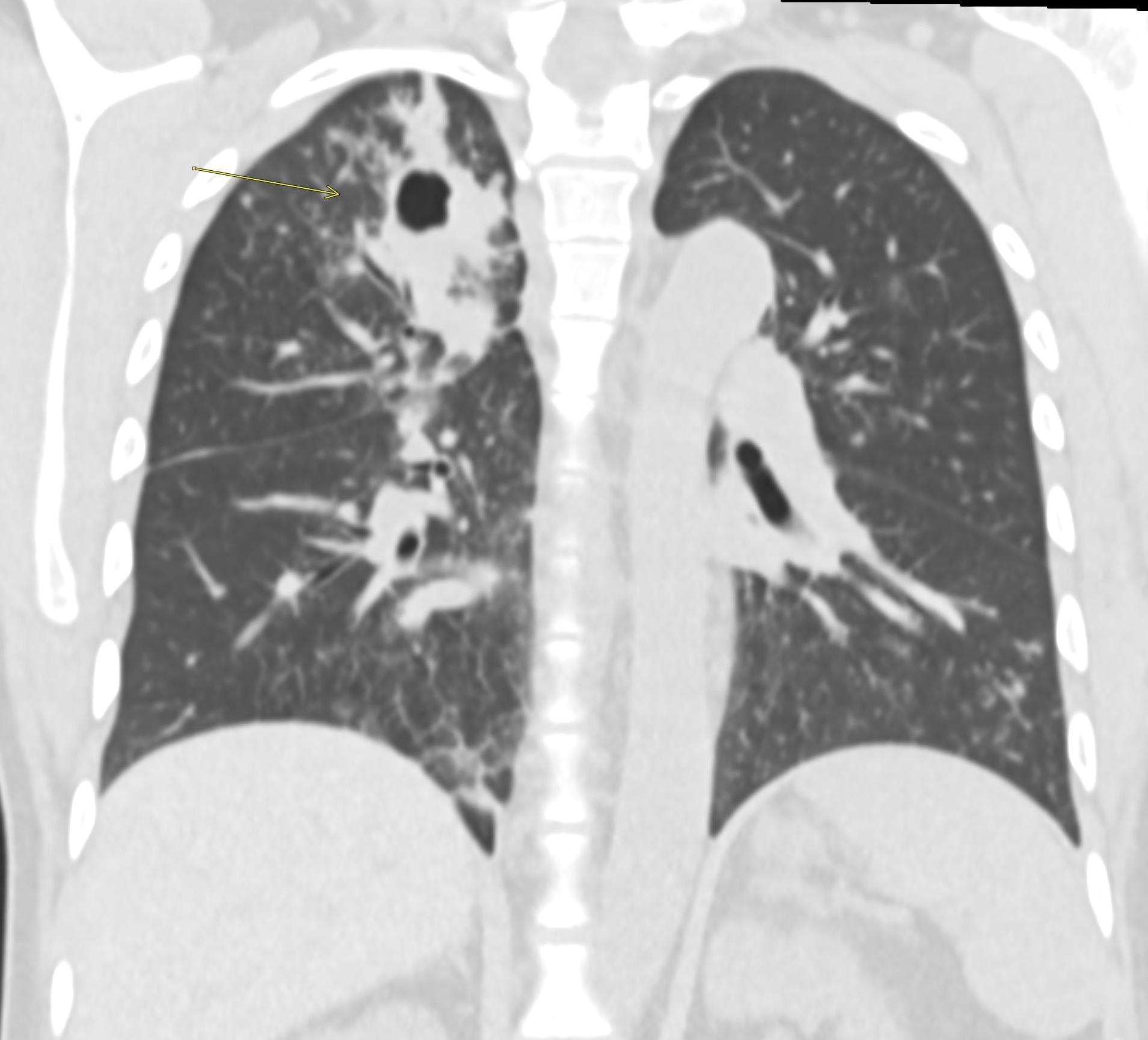

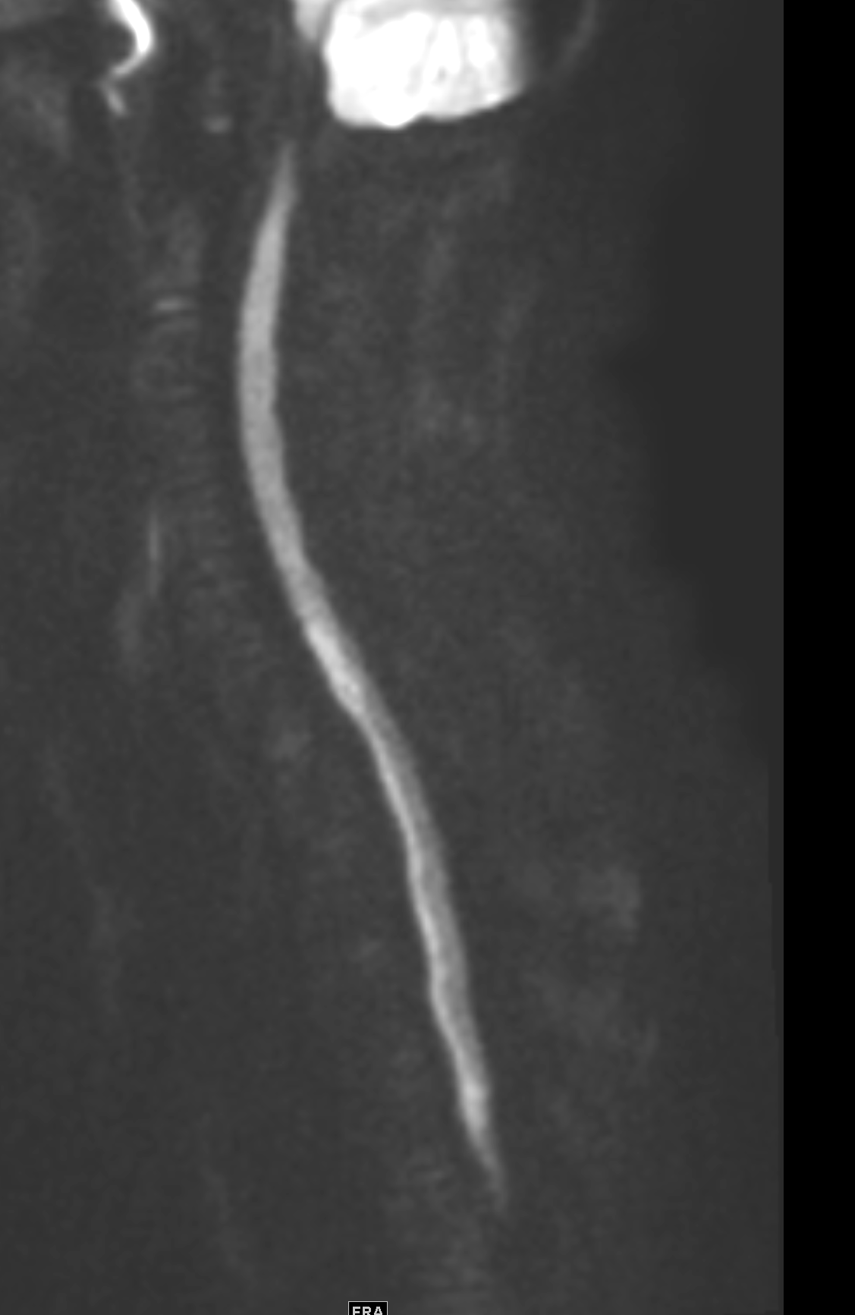

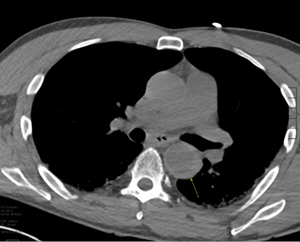

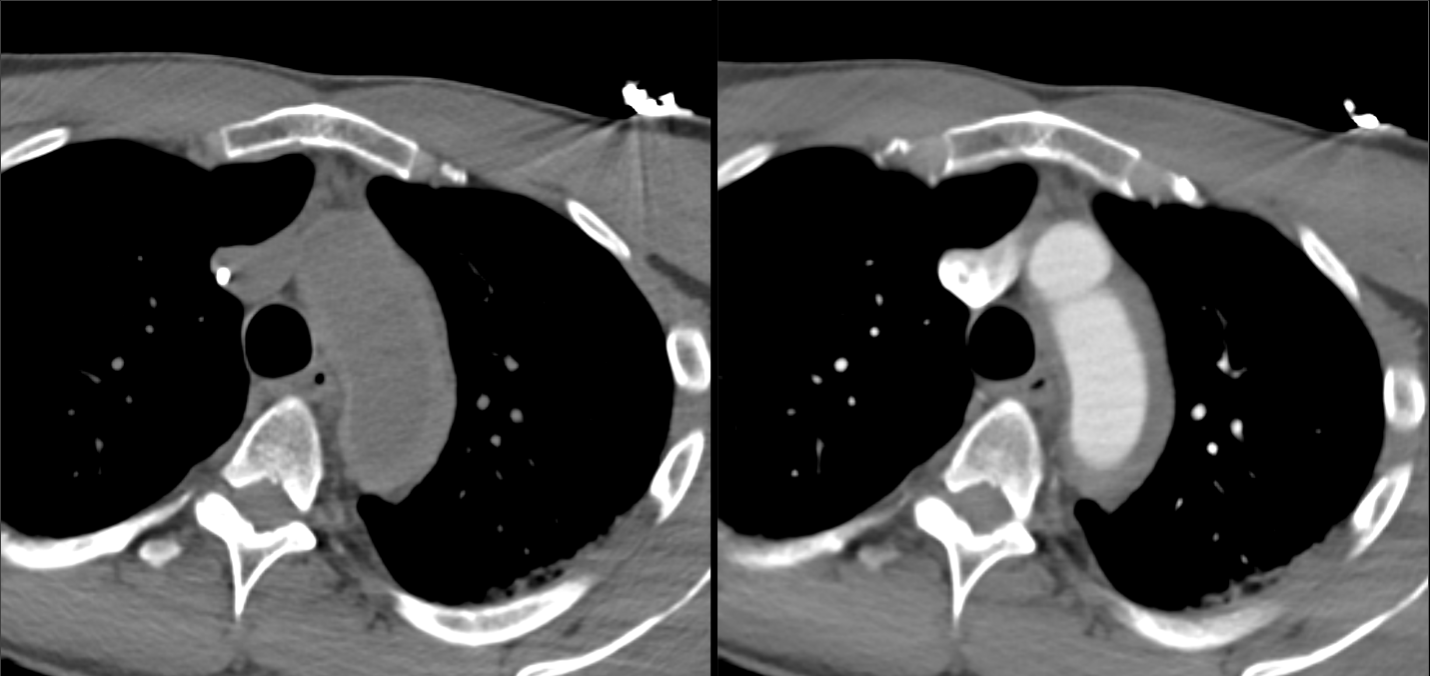

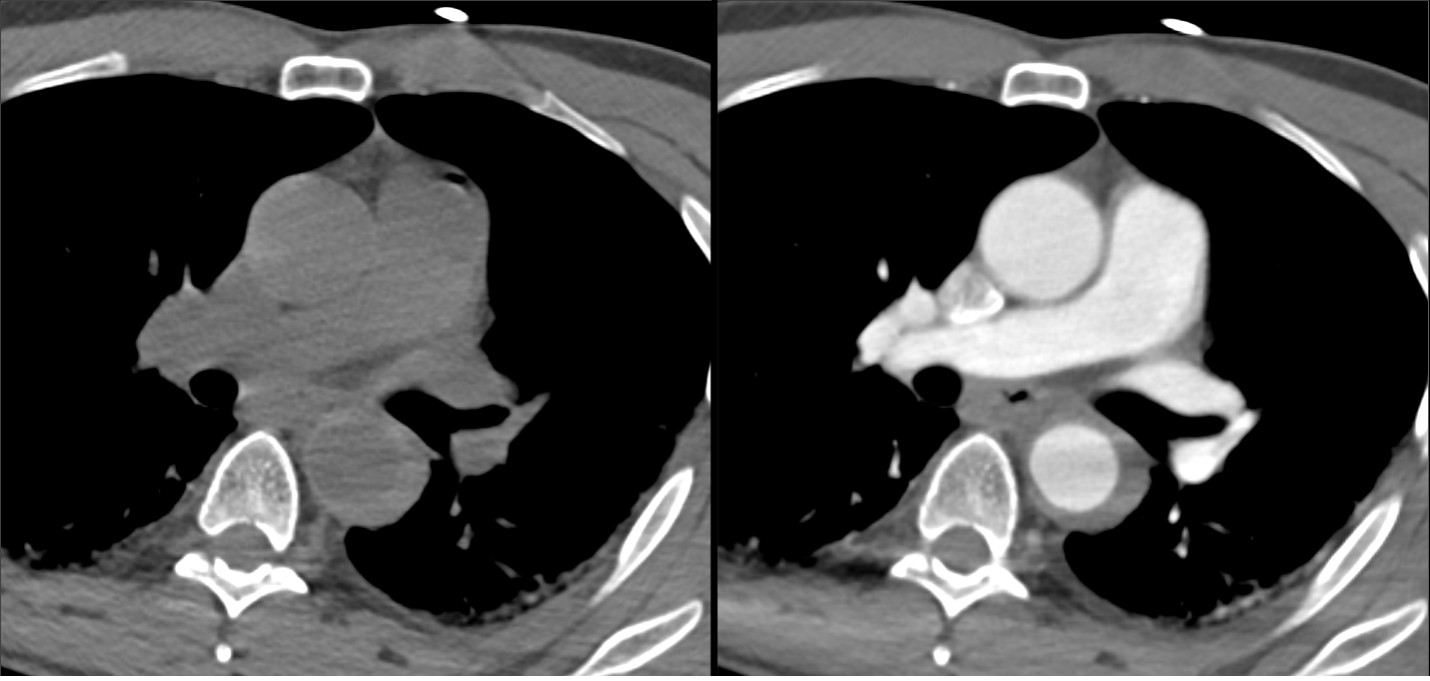

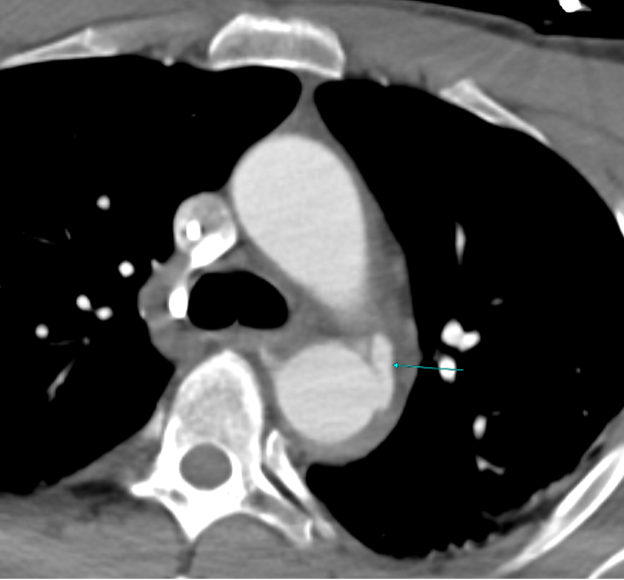

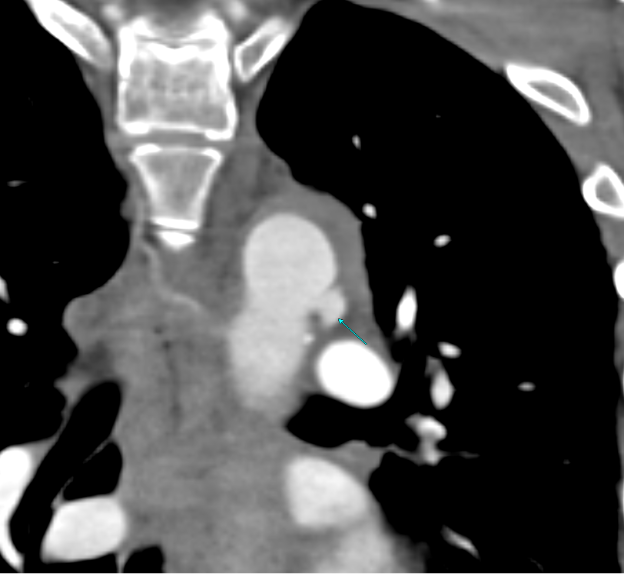

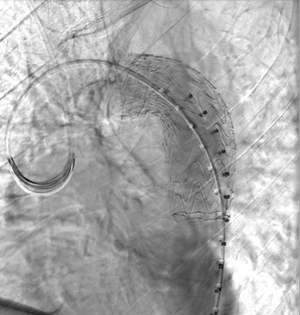

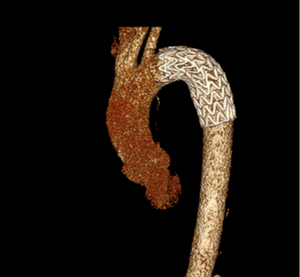

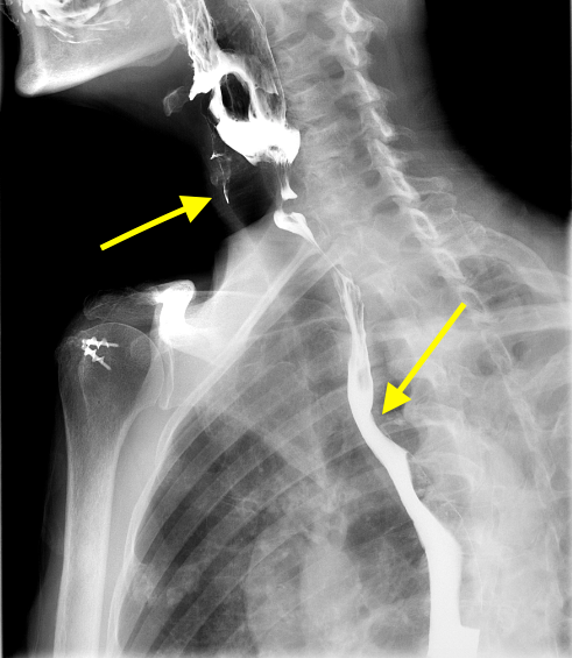

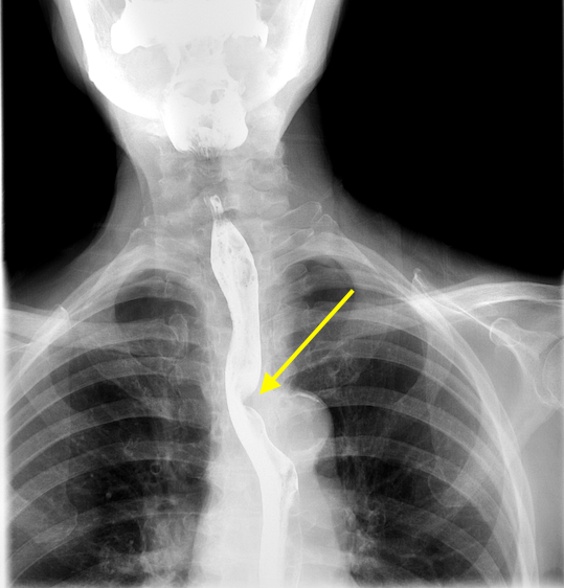

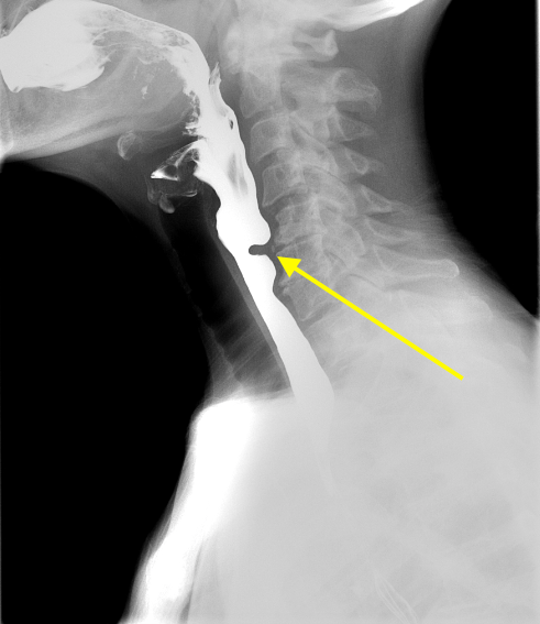

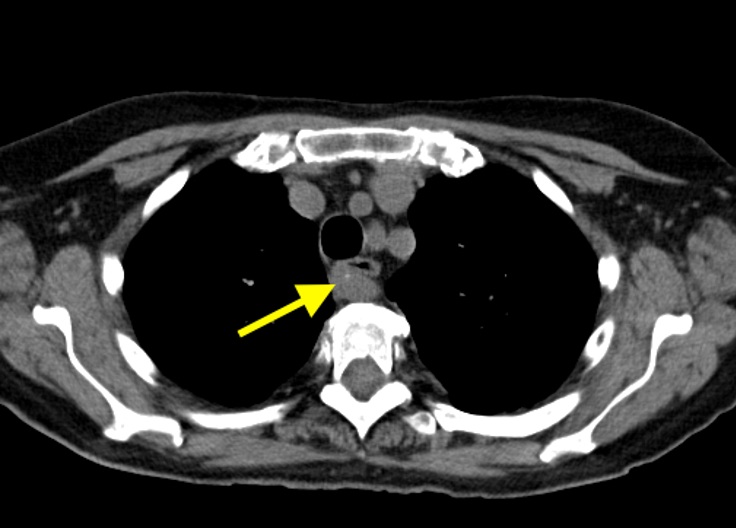

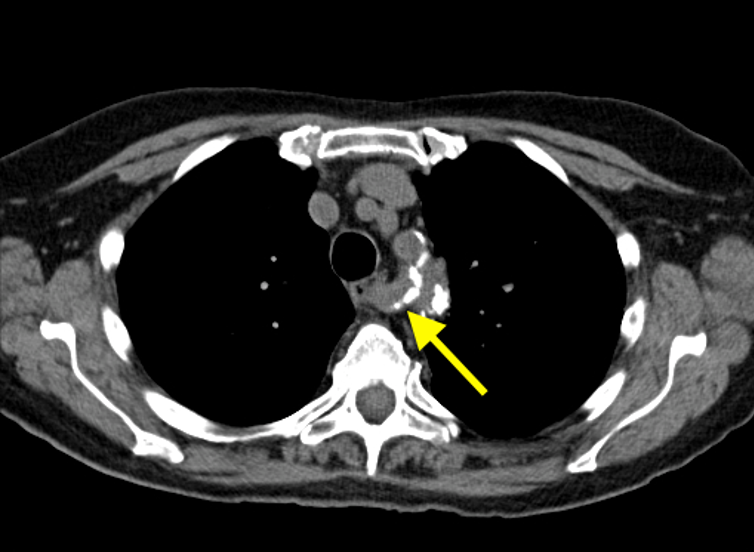

Imaging Findings: Pre-contrast CT of the chest reveals crescentic hyperdensity in the aortic wall beginning distal to the arch great vessels compatible with intramural hematoma (yellow arrow). Post contrast imaging demonstrates an irregular outpouching arising from the thoracic aorta at the level of the aortic isthmus compatible with a pseudoaneurysm (blue arrows). Intra-operative imaging during thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) shows a stent graft deployed over the aortic arch distal to the takeoff of the left subclavian artery. Follow up chest CTA reconstruction shows the appropriately positioned graft without opacification of the pseudoaneurysm.

Diagnosis: Traumatic aortic pseudoaneurysm and intramural hematoma.

Course: The patient was taken emergently to the operating room for thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) via left common femoral artery access. A stent graft was deployed covering the site of aortic injury. There was no evidence of endoleak on completion angiogram. The patient had an uneventful post-operative course and was discharged shortly thereafter. A follow up CT angiogram performed several months later showed no evidence of endoleak or surgical complication.

Discussion: Aortic trauma is a life-threatening injury which requires prompt diagnosis and intervention for survival. An estimated 85-90% of patients with these injuries will die in the field before they can be brought to the nearest hospital. Traumatic aortic injuries can include intimal tears, intramural hematoma, pseudoaneurysm, to complete transection of the aortic wall. Medical management includes impulse control with intravenous beta-blockers such as esmolol to reduce stress and shear on the aortic wall. Endovascular stent grafting is the preferred option for surgical intervention. Patients with unfavorable anatomy or extensive injuries may need open surgical repair which carries a higher risk of complication and longer recovery time.

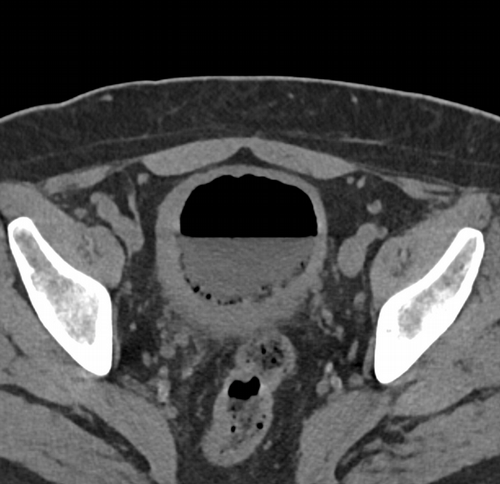

September 2024: Osteonecrosis of the Femur

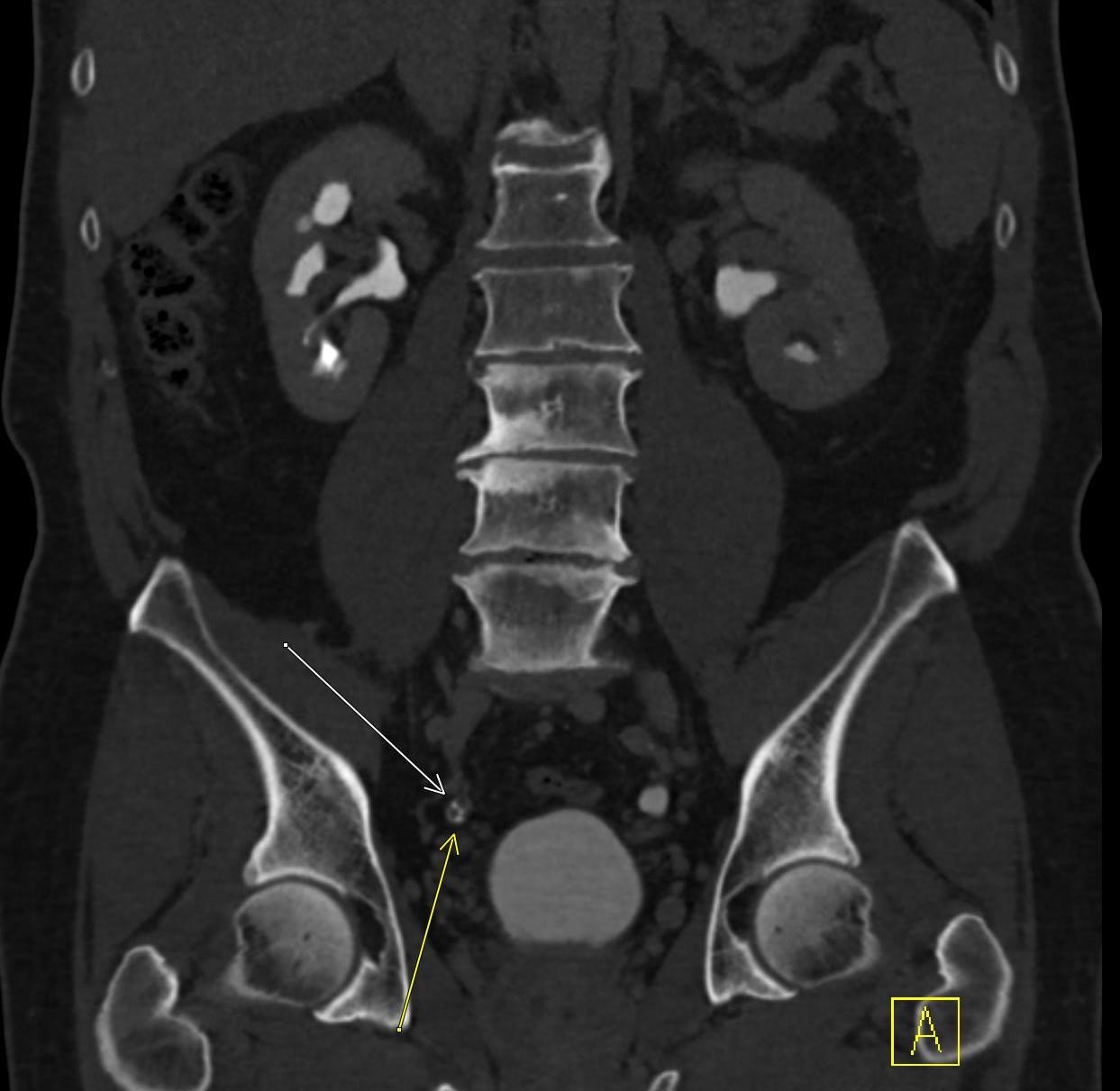

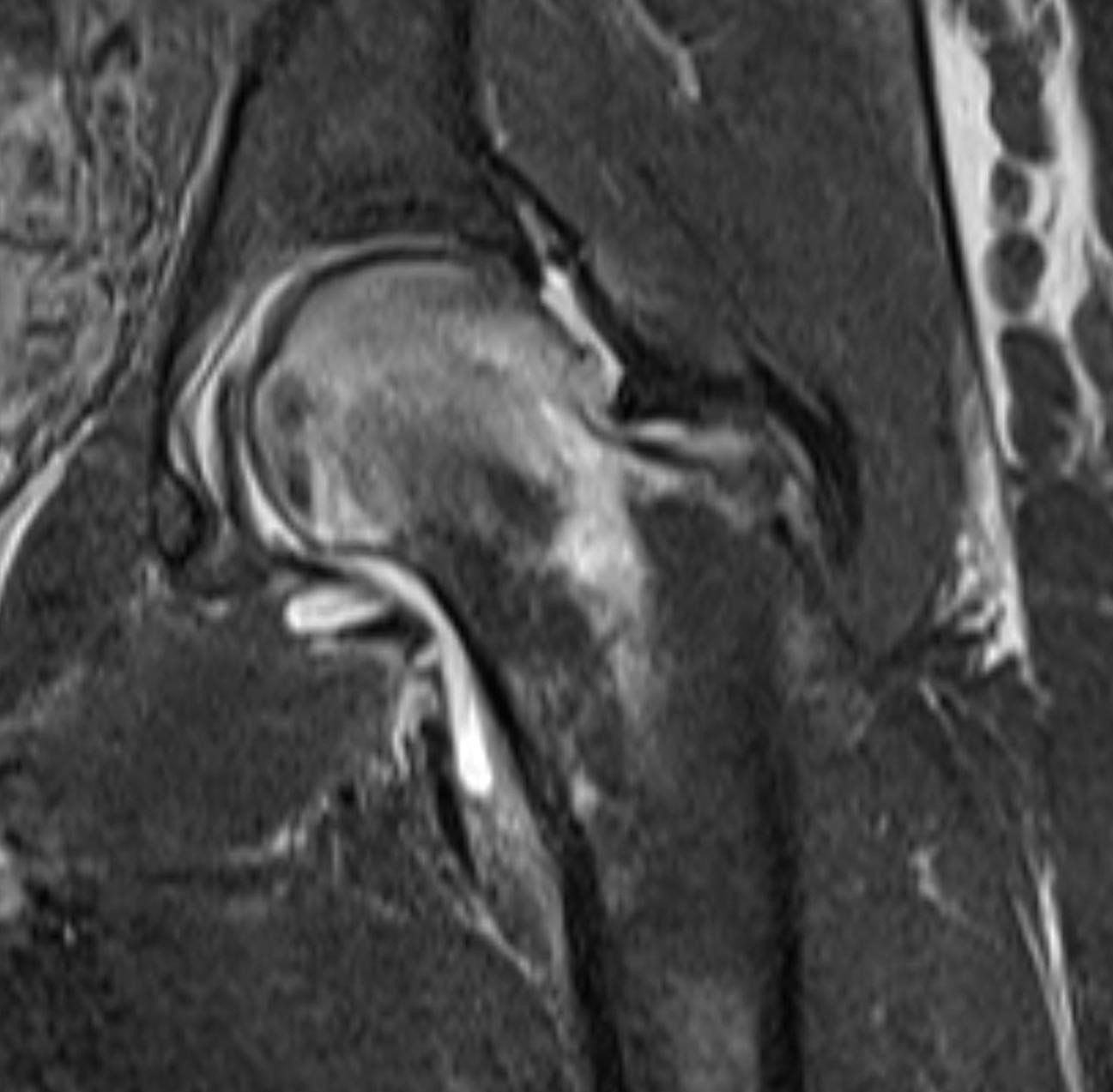

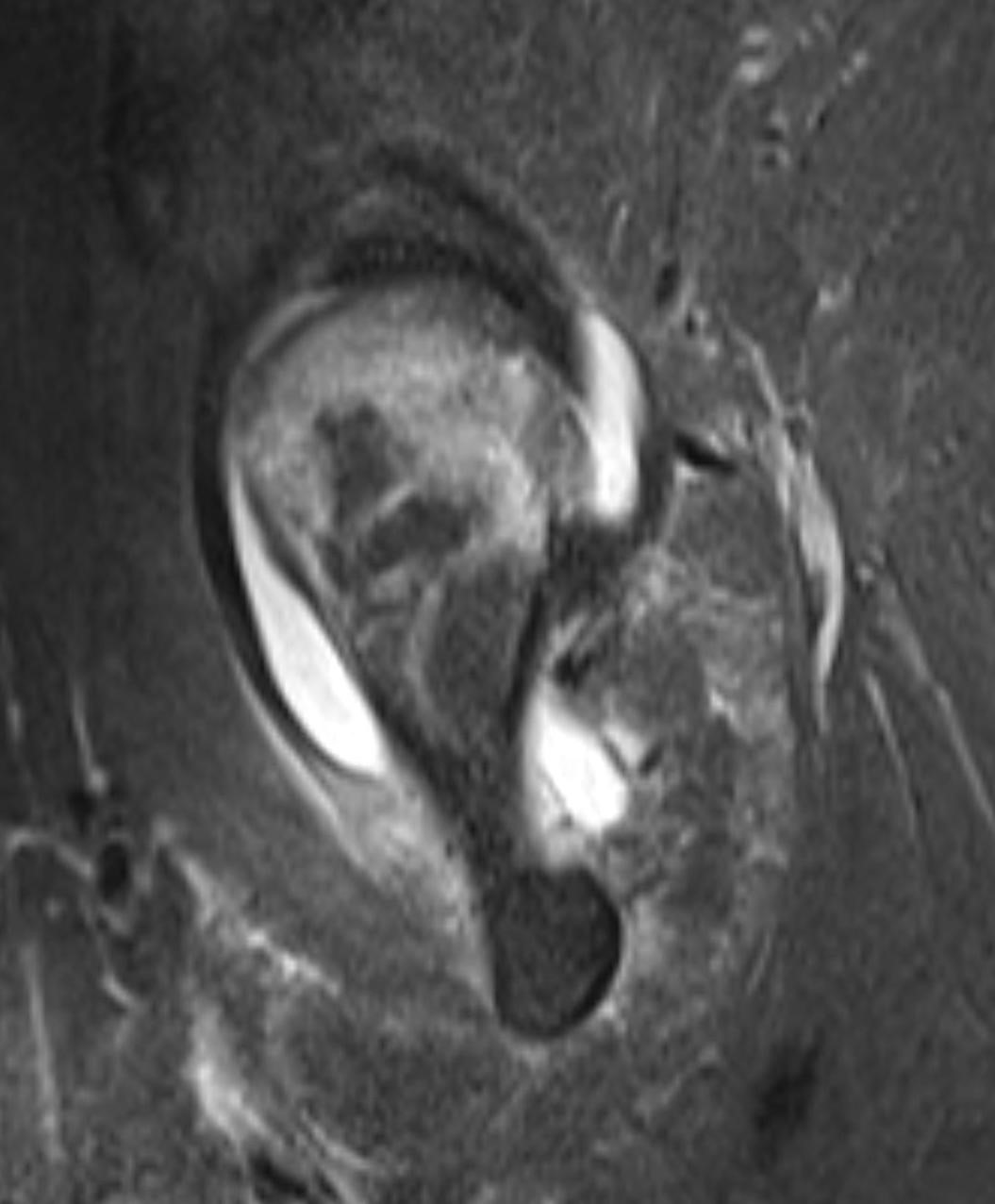

History: A young adult male presents with chronic right groin pain which exacerbates with activity. Hip range of motion was limited on physical exam. Imaging of the right hip was obtained.

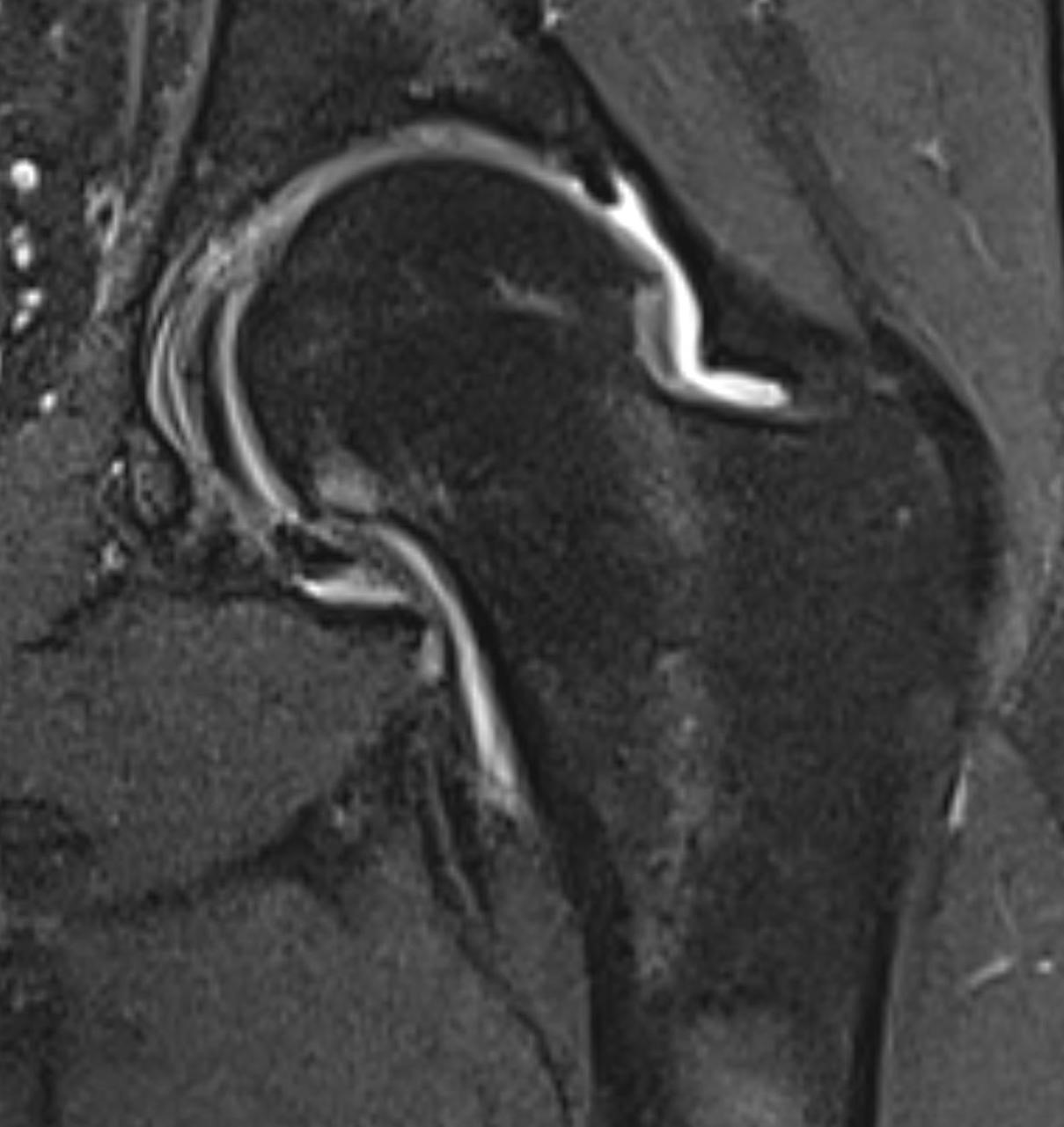

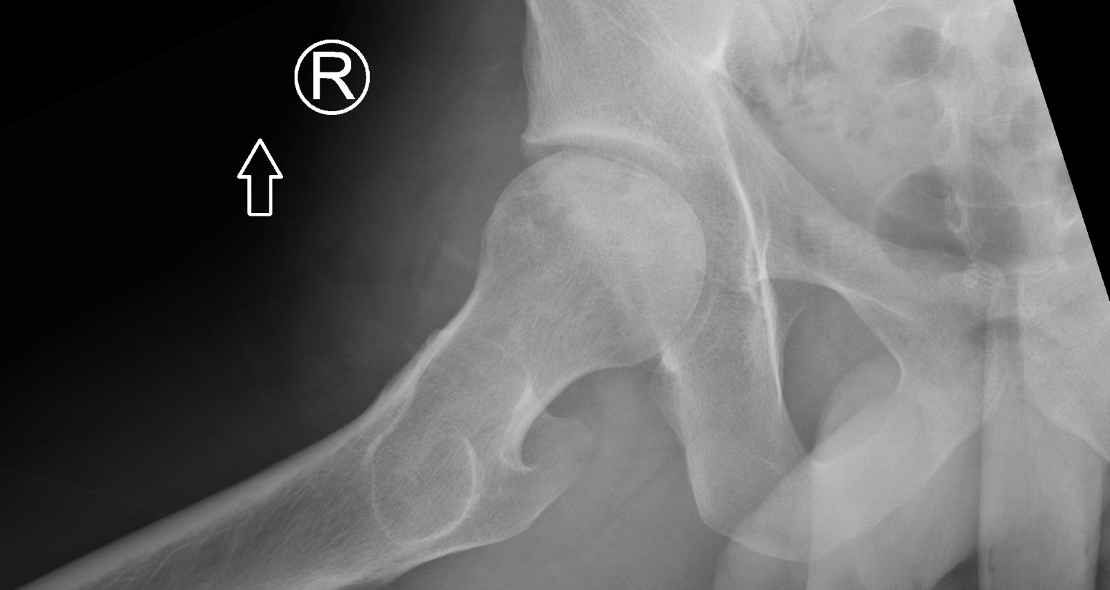

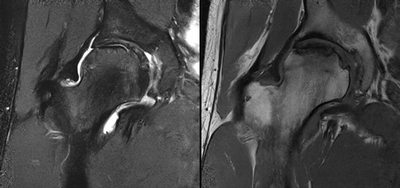

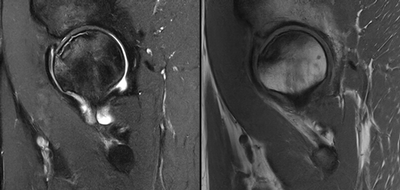

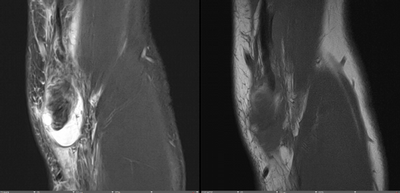

Imaging Findings: AP and lateral radiographs of the right hip reveals femoral head collapse and sclerosis with subchondral crescentic lucency. Follow up MRI confirms the findings of femoral head articular surface collapse with a curvilinear stripe of subchondral marrow edema demarcating the edematous and viable marrow from the necrotic, sclerosed marrow.

Diagnosis: Femoral head osteonecrosis with articular surface collapse

Course: The patient was prescribed physical therapy and as needed anti-inflammatory medication. He was advised that given the advanced stage of osteonecrosis at his young age, he will likely need a hip replacement in the future as the osteonecrosis progresses.

Discussion: Osteonecrosis is the death of bone tissue secondary to lack of blood flow. The condition usually affects the epiphyses of bones. Osteonecrosis has numerous etiologies but in most cases is idiopathic. Femoral head collapse, as seen in this case, is a finding of advanced osteonecrosis which predisposes to early osteoarthritis because the femoral head no longer rotates smoothly within the acetabulum. Initial treatment is generally conservative, however as the condition progresses surgical interventions such as decompressive osteotomy or total hip replacement are indicated.

August 2024: Gout

History: A middle-aged male presents with severe, acute onset lateral foot pain and swelling. On physical examination the first metatarsophalangeal joint was warm, edematous, and tender to palpation. Serum uric acid was elevated. Radiographs of the foot were ordered.

Imaging Findings: Coned down AP projection centered on the first metatarsal head reveals an osseous erosion with overhanging edge (blue arrow) and adjacent soft tissue mineralization compatible with tophus (pink arrow). There is no joint space narrowing, peri-articular osteopenia, or osteophyte formation.

Diagnosis: Gout

Course: The patient was prescribed colchicine with rapid resolution of symptoms. Allopurinol was prescribed for prevention of future gout flares. The patient was counseled to achieve a normal body mass index and reduce consumption of alcohol and meats high in purine content such as beef, liver, and shellfish. Several months after this presentation, the patient was doing well without subsequent gout flares.

Discussion: Gout is an inflammatory crystalline arthropathy resulting from articular and peri-articular deposition of monosodium urate crystals. Radiography can demonstrate bone erosions with overhanging edges and soft tissue tophus formation, as seen in this case. Dual energy CT can also assess for presence of uric acid deposition. The most common sites of involvement are the metatarsophalangeal joints, knee, ankle, and wrist. Risk factors include male gender, obesity, excessive alcohol, soda, and/or meat consumption, and certain medications such as diuretics. Treatment is a combination of lifestyle modification and pharmacologic agents.

July 2024: Biceps Tendon Rupture

History: A young male presented with acute arm pain and swelling after catching a heavy box while helping his friend move. Clinically there was concern for biceps tendon rupture. Imaging of the arm was performed.

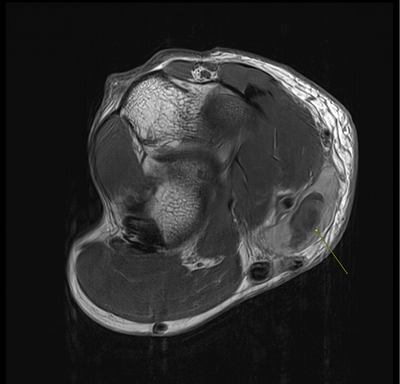

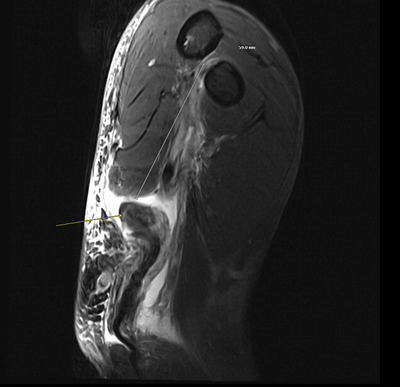

Imaging Findings: The elbow radiograph lateral projection is notable for a popeye sign, with bulging soft tissue in the region of the distal biceps, highly concerning for biceps tendon rupture. The follow up elbow MRI reveals complete rupture of the distal biceps tendon. The tendon stump is thickened and edematous with surrounding fluid. The tendon stump is retracted approximately 5.9 cm proximal to its insertion on the radial tuberosity.

Diagnosis: Distal biceps tendon rupture.

Hospital Course: The patient underwent biceps tendon repair the next day with orthopedic surgery. The tendon was anchored to the radial tuberosity with suture. The patient was discharged and did well with outpatient physical therapy. He reported no residual deficit in supination or elbow flexion six months after the surgery.

Discussion: The biceps brachii consists of two heads originating from the coracoid process (short head) and the supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula (long head). The heads fuse into one tendon which inserts onto the radial tuberosity. The biceps tendon is a strong supinator of the forearm and assists with elbow flexion. Proximal biceps tendon rupture is commonly seen in older patients and is more common than distal biceps rupture in this population. Distal tendon rupture is more common in younger patients who are athletes or weightlifters. Injury to the distal tendon usually requires surgical repair but can be treated conservatively if loss of supination and elbow flexion strength is acceptable to the patient.

June 2024: Acute Embolic Stroke

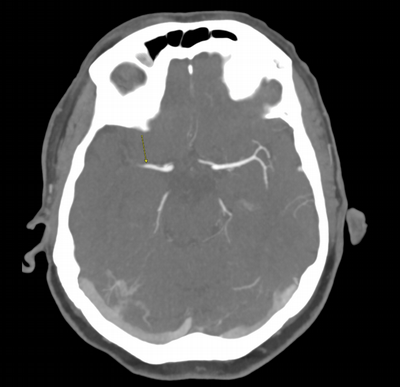

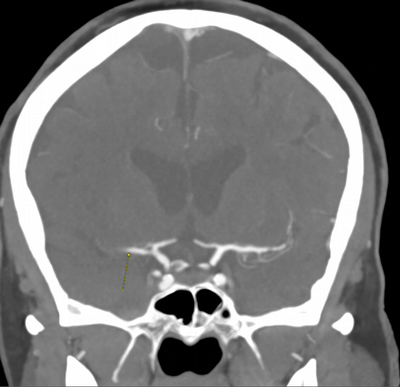

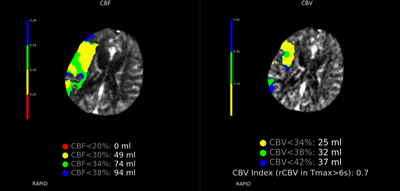

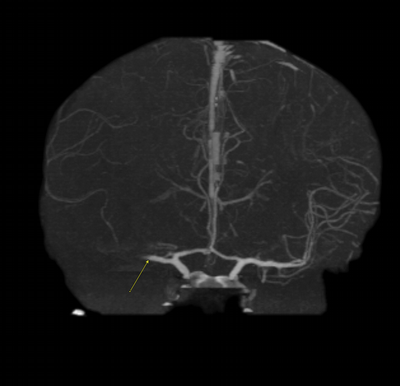

History: An elderly patient presented to the emergency department with acute onset left sided weakness and altered mental status. Physical exam was notable for left facial droop, left arm, and left leg weakness. Stroke code was activated and CT imaging of the head was performed. NIH stroke score was 23 per the stroke service.

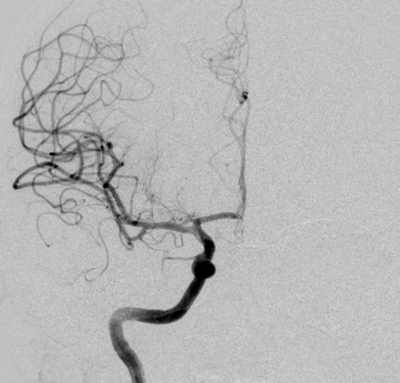

Imaging Findings: The initial non-contrast CT head (not shown) was unremarkable, without hemorrhage or territorial hypoattenuation. CT angiogram revealed abrupt cutoff of the right M1 segment and non-opacification of the M2 superior division. CT perfusion reveals an ischemic penumbra in the right MCA territory with a smaller ischemic core. Coronal digital subtraction angiography performed in the interventional neuroradiology suite confirms the large vessel occlusion in the distal right M1 segment. Post-thrombectomy coronal DSA shows restored perfusion in the MCA M1 segment and M2 superior division.

Diagnosis: Acute right MCA territory ischemic infarct secondary to occlusion of the middle cerebral artery at the origin of the M2 superior division.

Hospital Course: The initial head CT revealed no intracranial hemorrhage. The patient arrived within the window for pharmacological thrombolysis and received IV tenecteplase. Neurointerventional radiology took the patient for emergent thrombectomy which successfully restored perfusion to the right M2 superior division. Subsequently, the patient recovered some function of their left side. Workup revealed a new diagnosis of atrial fibrillation, suggesting a cardioembolic etiology of the stroke.

Discussion: Acute ischemic stroke is the onset of focal neurological deficits in a vascular territory affecting the brain or spinal cord due to reduced or absent perfusion. Stroke accounts for 1 in 6 deaths from cardiovascular disease. Annually, over 795,000 Americans suffer from a stroke annually. The financial burden of stroke in the US amounted to $56 billion in 2019. The MCA is the most common artery involved in stroke, with characteristic presentation of facial droop and upper>lower extremity weakness. Rapid diagnosis and treatment are crucial to preserve as much brain tissue as possible. Noncontrast CT brain imaging is required to rule out hemorrhage before initiating fibrinolytic agents such as alteplase and Tenecteplase. Endovascular thrombectomy is an option in select patients with large vessel occlusions, such as in this case.

May 2024: Splenic Trauma

History: A middle-aged male presented to the emergency department with left upper quadrant pain. He reported recent blunt trauma to the area. He was hemodynamically stable with left upper quadrant tenderness on physical exam. Lab work was within normal limits. A CT angiogram of the abdomen and pelvis was performed given the concern for splenic injury.

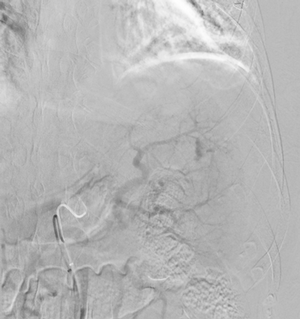

Imaging Findings: Pre-contrast images demonstrate hyperdense fluid representing hemoperitoneum surrounding the spleen. Arterial phase images demonstrate abnormal foci of enhancement within the splenic parenchyma compatible with pseudoaneurysms given the setting of trauma. Blood products are seen pooling within the spleen representing intrasplenic hematomas. Digital subtraction angiography with selective catheterization of the splenic artery reveals the splenic pseudoaneurysms in greater spatial resolution. Status post embolization with coils and gelfoam, the pseudoaneurysms no longer fill with contrast signifying successful treatment.

Diagnosis: Traumatic splenic artery pseudoaneurysms.

Hospital Course: The patient was taken urgently to the Interventional Radiology angiosuite for invasive angiography. Selective catheterization of the splenic artery revealed multiple pseudoaneurysms, concordant with the CTA findings. The pseudoaneurysm were embolized with coils and gelfoam with no residual filling. The patient did well post-operatively with stable hemoglobin levels. He was discharged home the next day.

Discussion: The spleen is a highly vascular organ and one of the most commonly injured organs in the setting of abdominal trauma. Missed or delayed diagnosis of splenic trauma can result in acute blood loss anemia, hypovolemic shock, and death. Radiologic grading of splenic trauma helps determine the treatment strategy. Treatment options range from blood transfusions, endovascular embolization, or operative splenectomy. Splenectomy is the most invasive treatment and avoided if possible as it raises risk of post-splenectomy sepsis secondary to encapsulated bacteria (Streptococcus, Neisseria meningitis, and Haemophilus influenzae type B). Interventional radiologists perform splenic artery embolization either as definitive therapy, such as in this case, or before surgery to reduce bleeding during the splenectomy.

April 2024: Emphysematous Cystitis

History: A middle-aged patient with a history of poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus complicated by neurogenic bladder and recurrent urinary tract infections presented to the emergency department with dysuria, pneumaturia, and chills. Physical exam demonstrated suprapubic tenderness without costovertebral angle tenderness. Lab work was notable for leukocytosis and bacteriuria on urinalysis. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was performed.

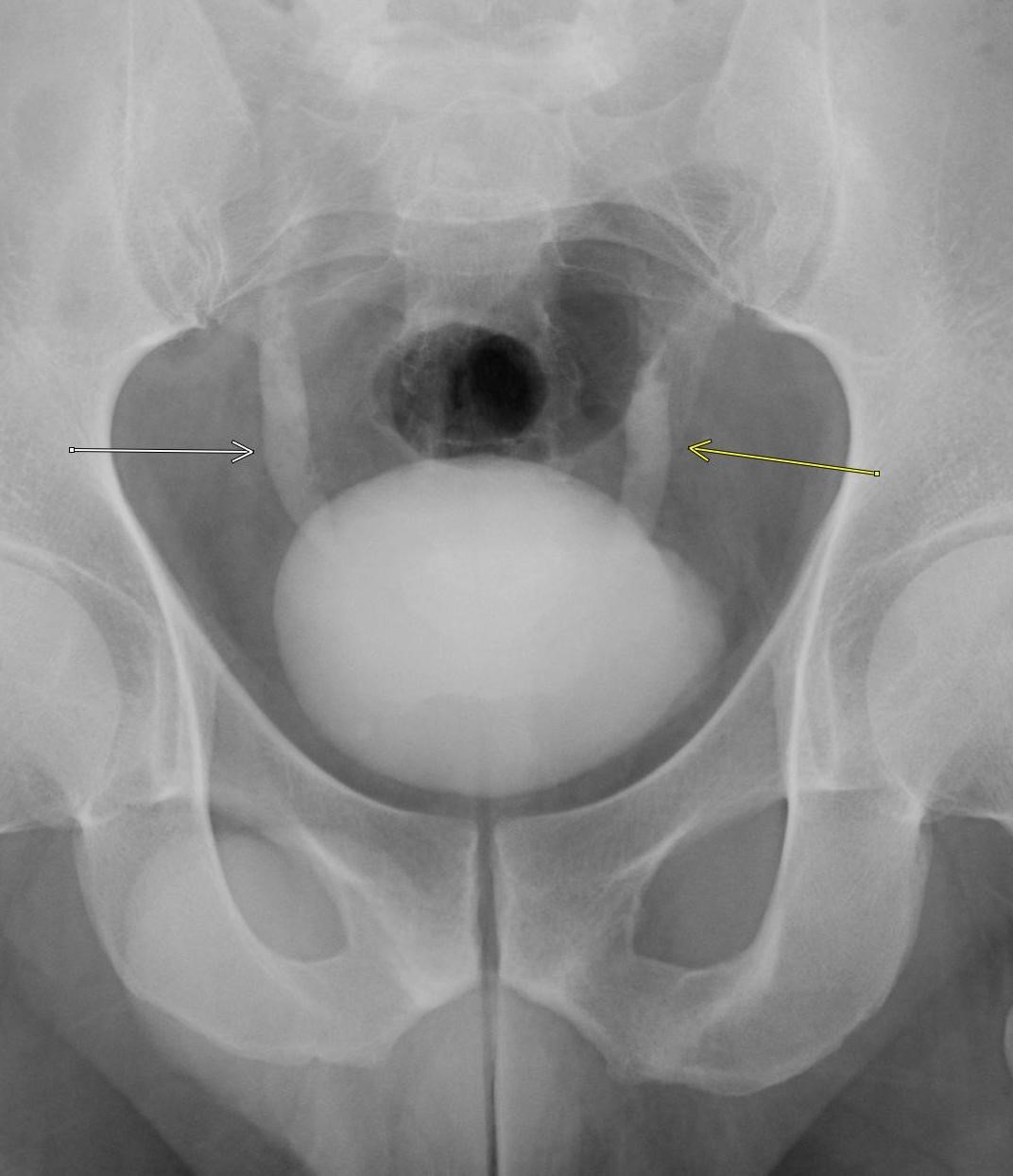

Imaging Findings: CT of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrates numerous small foci of air in the bladder adjacent to the non-dependent portion of the bladder mucosa. There is also bladder wall thickening out of proportion to the degree of underdistension. The kidneys (not pictured) demonstrated symmetric nephrograms without evidence of pyelonephritis. There were no urothelial stones.

Diagnosis: Emphysematous cystitis.

Hospital Course: A foley catheter was placed in the emergency department and IV antibiotics were initiated. Urine culture grew Klebsiella pneumoniae. The patient improved symptomatically, and his leukocytosis normalized. He was discharged home with the foley catheter and oral antibiotics with a plan for short term follow-up with the urology service. He did well with medical management and the foley catheter was removed. He was counseled on the importance of managing his diabetes.

Discussion: Emphysematous cystitis is a rare complication of cystitis. It is most commonly seen in the setting of poorly controlled diabetes, neurogenic bladder, recurrent urinary tract infections, or in patients with an immucompromised state. Symptoms may include pneumaturia or dysuria although some patients are asymptomatic. Delay in diagnosis or treatment can result in the feared complication of emphysematous pyelonephritis which has high mortality and is managed with urgent nephrectomy. Imaging is the gold standard for diagnosis and used to evaluate for complications such as abscess, infected urothelial stones, or pyelonephritis.

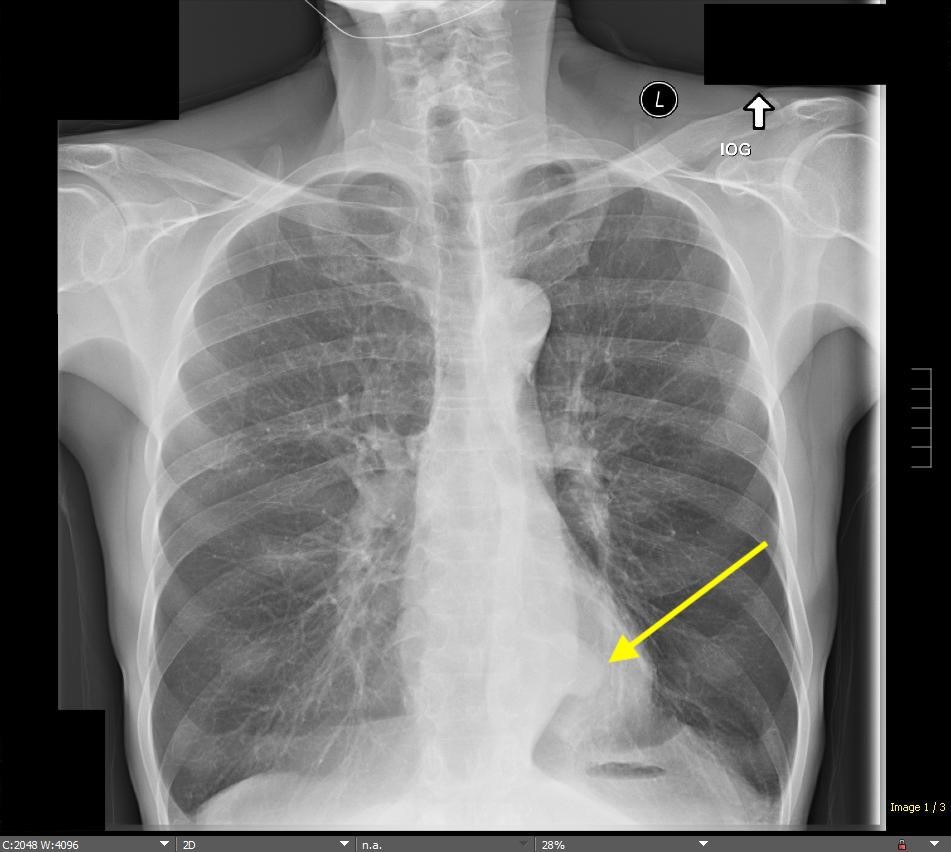

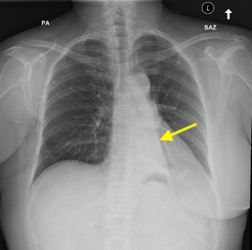

March 2024: Tension Pneumothorax

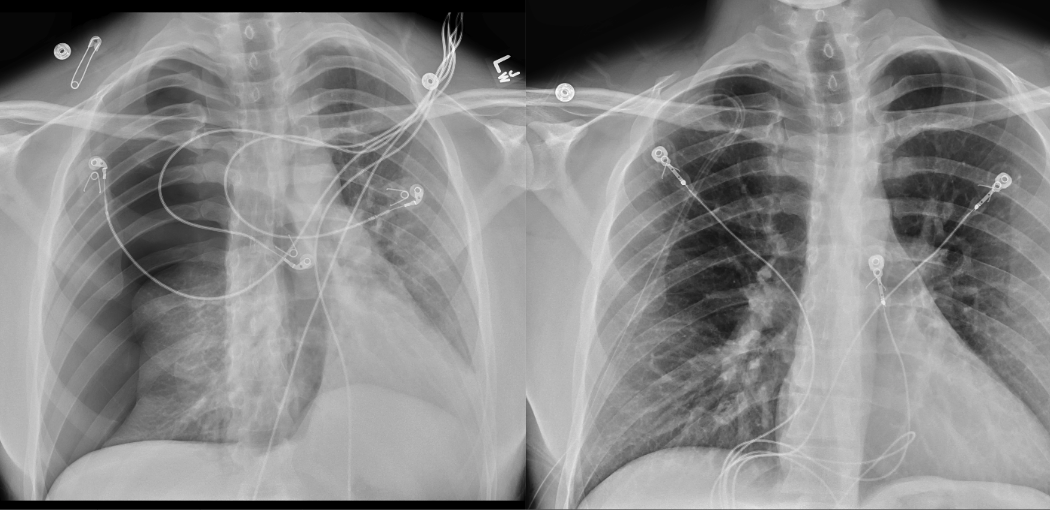

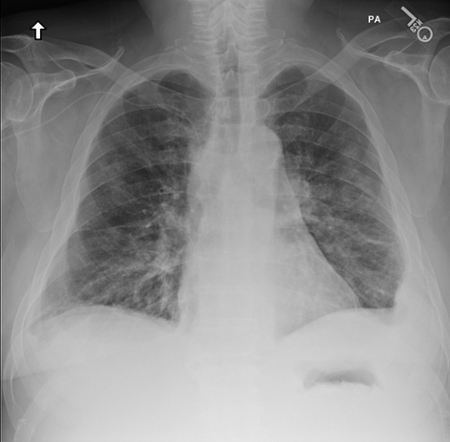

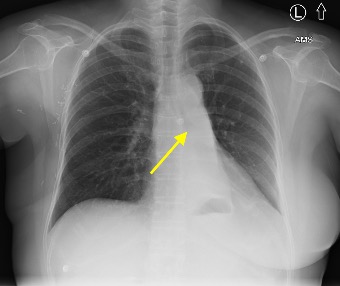

History: A young male with no past medical history presented to the emergency department with acute onset chest pain and shortness of breath which woke the patient from sleep. Physical exam revealed decreased breath sounds on the right. A stat chest radiograph was ordered.

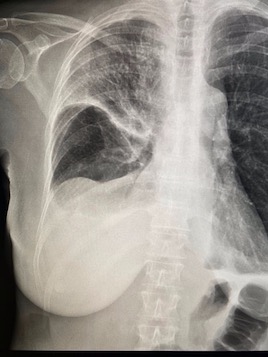

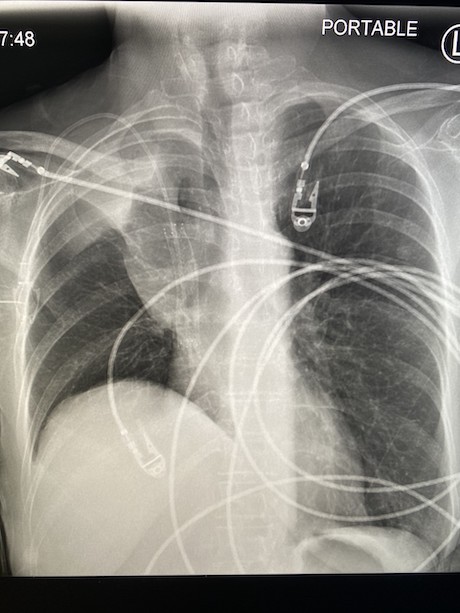

Imaging Findings: The initial chest radiograph (screen left) reveals a large right pneumothorax with leftward mediastinal shift, diaphragmatic flattening, and mass effect on the right side of the heart indicating tension physiology. The post chest tube placement radiograph (right) demonstrates re-expansion of the right lung. The mediastinal shift, diaphragmatic depression, and mass effect on the heart has resolved.

Diagnosis: Right tension pneumothorax.

Hospital Course: A chest tube was emergently placed by interventional radiology under fluoroscopic guidance with immediate resolution of the patient’s symptoms. While hospitalized, the patient underwent workup for underlying pulmonary disease or connective tissue abnormality which can predispose to pneumothorax. No underlying abnormality was discovered, and a diagnosis of primary spontaneous pneumothorax was given. The chest tube was clamped and removed without pneumothorax recurrence. The patient was discharged with precautions to avoid Valsalva maneuver and scuba diving. If pneumothorax ever recurs, he will be referred to thoracic surgery for definitive management.

Discussion: Pneumothorax is the accumulation of air in the pleural space. Tension physiology indicates progressive accumulation of pressure, which can cause compression of the airway, great vessels, and heart leading to cardiac arrest and death. Disruption of the pleura from trauma or underlying lung disease are the most common etiologies. Tension pneumothorax must be treated with prompt needle decompression or chest tube placement to allow the air trapped in the pleural space to escape. If the pneumothorax does not resolve with these measures, thoracotomy or video-assisted thorascopic surgery is performed and the pleural space is obliterated.

February 2024: Intracranial Abscesses

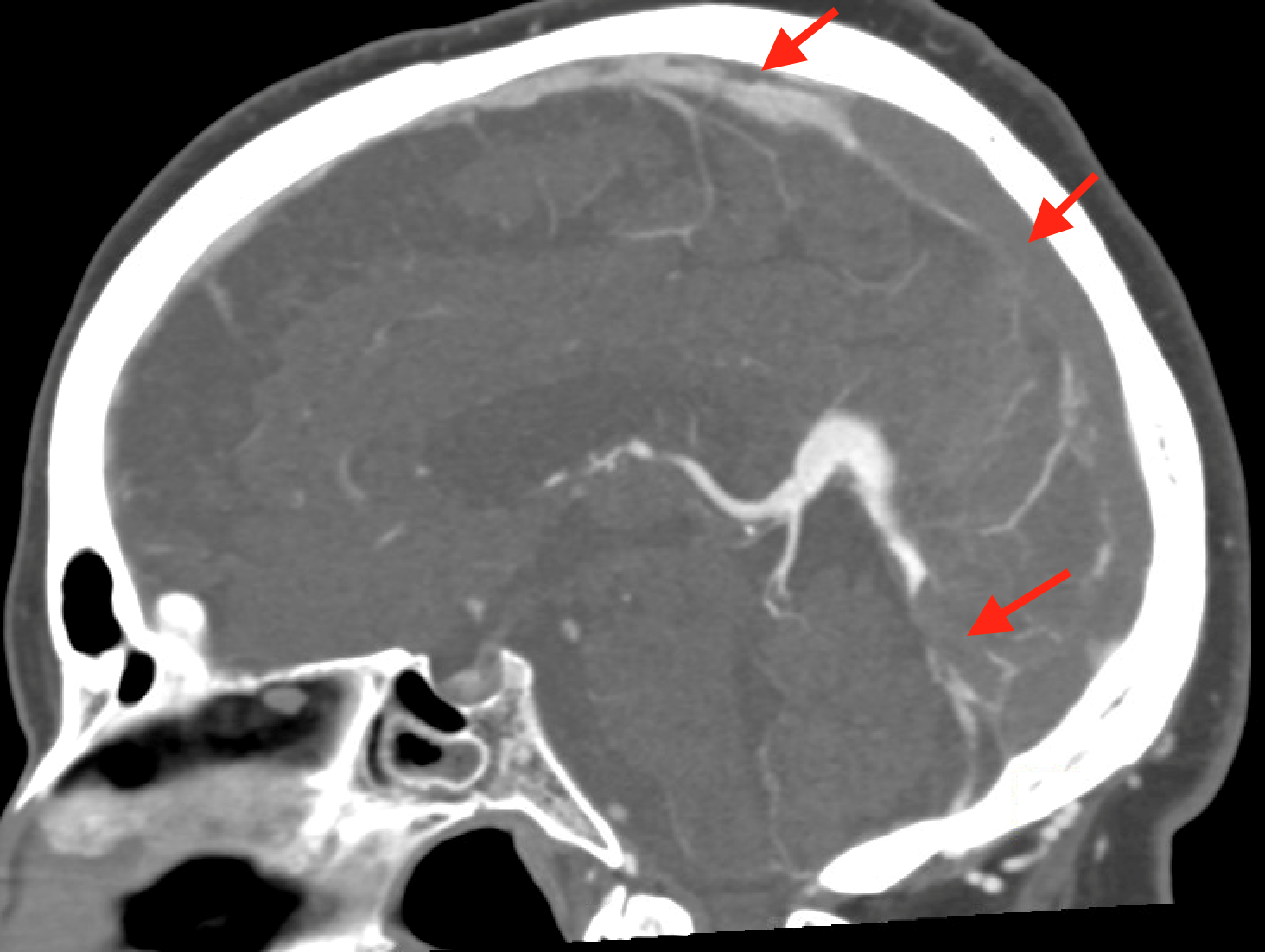

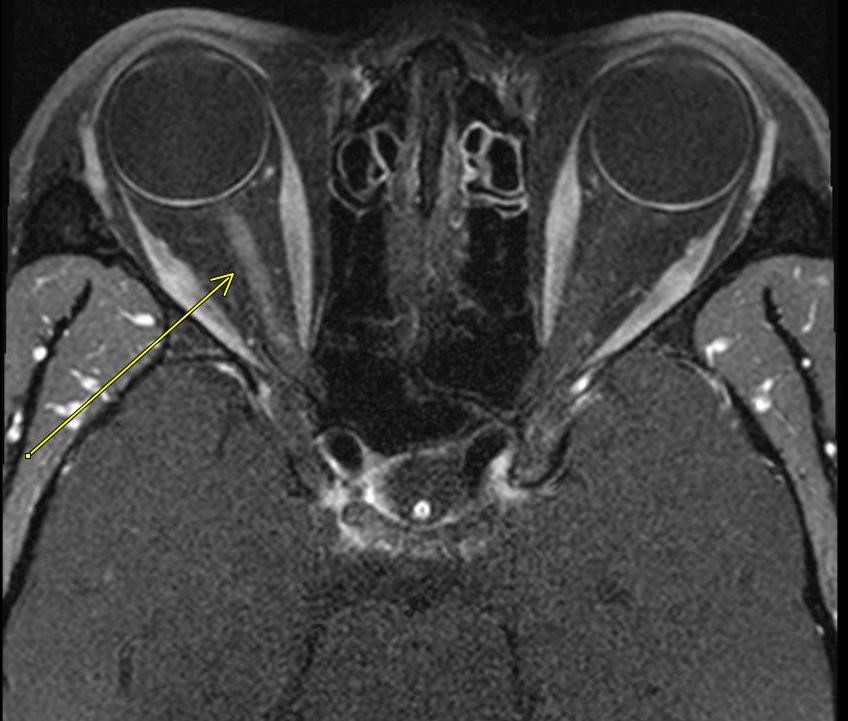

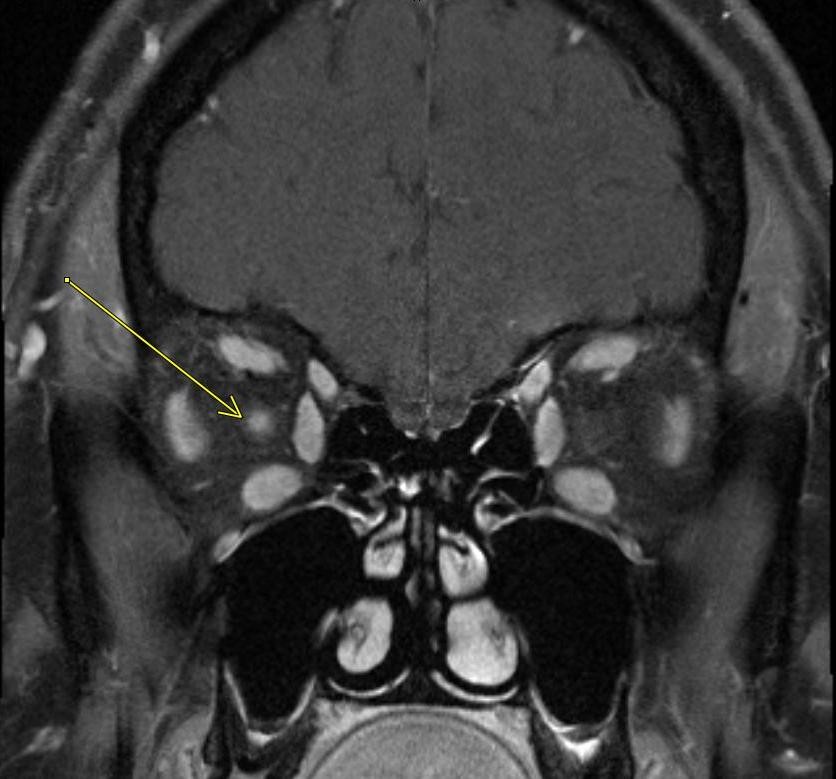

History: A previously healthy young adult presented to the emergency department with fever and altered mentation. Physical exam revealed receptive aphasia, extremity weakness, and right facial droop. Lab work was unremarkable. Cross-sectional imaging of the brain was ordered.

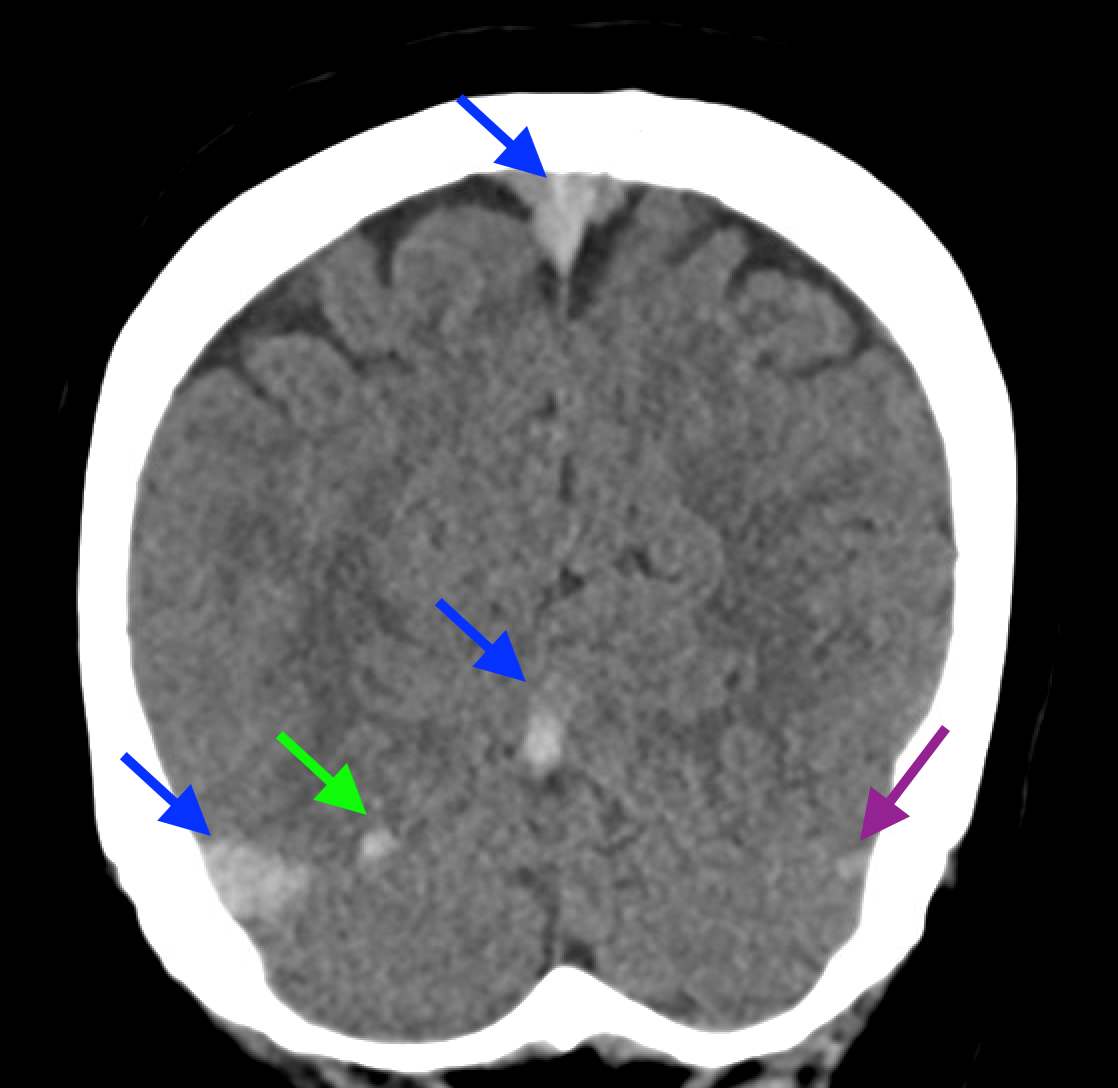

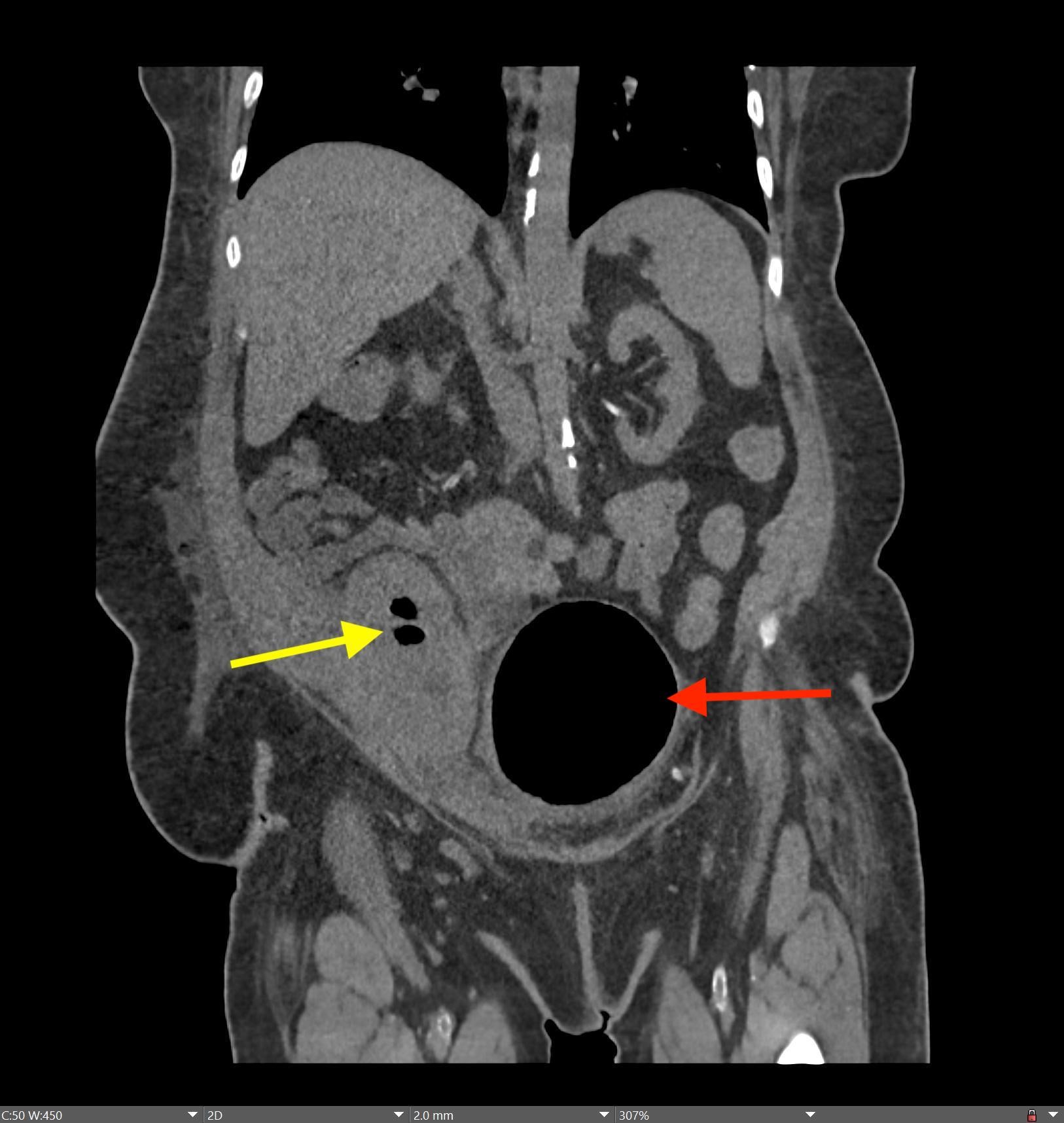

Findings:

Non-contrast brain CT revealed rounded areas of hypoattenuation in the left frontal lobe (blue arrows). Follow-up brain MRI with contrast revealed rim enhancing lesions of varying sizes in the right frontal and parietal lobes with associated diffusion restriction. There is a peripherally enhancing subdural fluid collection overlying the right frontal convexity (red arrows). Confluent T2 and FLAIR hyperintense signal surrounds the enhancing lesions. Mass effect results in rightward midline shift.

Diagnosis: Intracranial abscesses with subdural empyema.

Hospital Course: The patient underwent left frontoparietal craniectomy and washout with neurosurgery. The subdural empyema was evacuated and the larger abscesses located peripherally in the brain were drained. The smaller abscesses deeper in the brain were not suitable for operative intervention given their sensitive location. Post-operatively the patient’s aphasia and extremity weakness improved. Surgical cultures grew Fusobacterium necrophorum, an anaerobic gram-negative rod. Infectious disease recommended treatment with IV penicillin and oral metronidazole until there was clinical and imaging evidence of resolution. Follow up imaging three months later revealed resolution of the abscesses with no evidence of recurrent infection and the antibiotics were discontinued. The patient subsequently underwent cranioplasty with plastic surgery to restore the left craniectomy defect.

Discussion: Intracranial infection can result from bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites, and rarely prions. Transmission can occur via direct local spread from head trauma, paranasal sinusitis, or hematogenous spread in the setting of septicemia. Presenting symptoms include headache, mental status change, fever, and seizures. White blood cell count can be normal, as it was is in this case. MRI with contrast is the gold standard to diagnose complications of intracranial infection such as intracranial abscesses, empyema, ventriculitis, and sinus venous thrombosis. Treatment typically involves antibiotic administration with the need for surgical intervention determined by the presence of the complications described above.

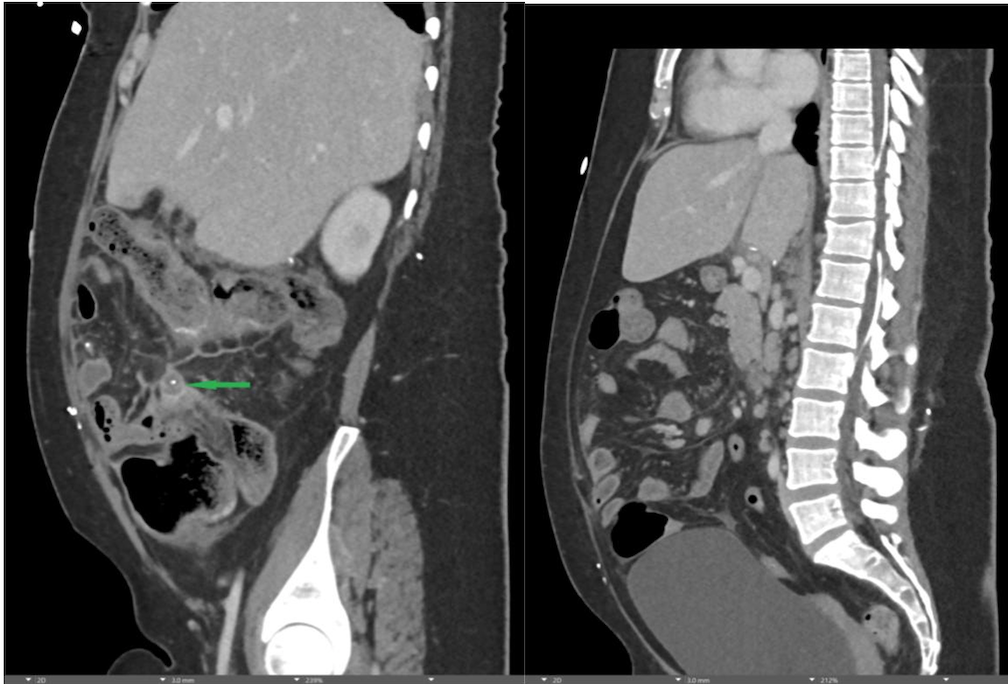

January 2024: Perforated Acute Appendicitis

History: A young adult presented to the emergency department with several days of abdominal pain. History was notable for a congenital intracranial malformation treated with a lumboperitoneal shunt. Physical exam revealed right abdominal tenderness to palpation. Lab work was notable for leukocytosis of 22,000.

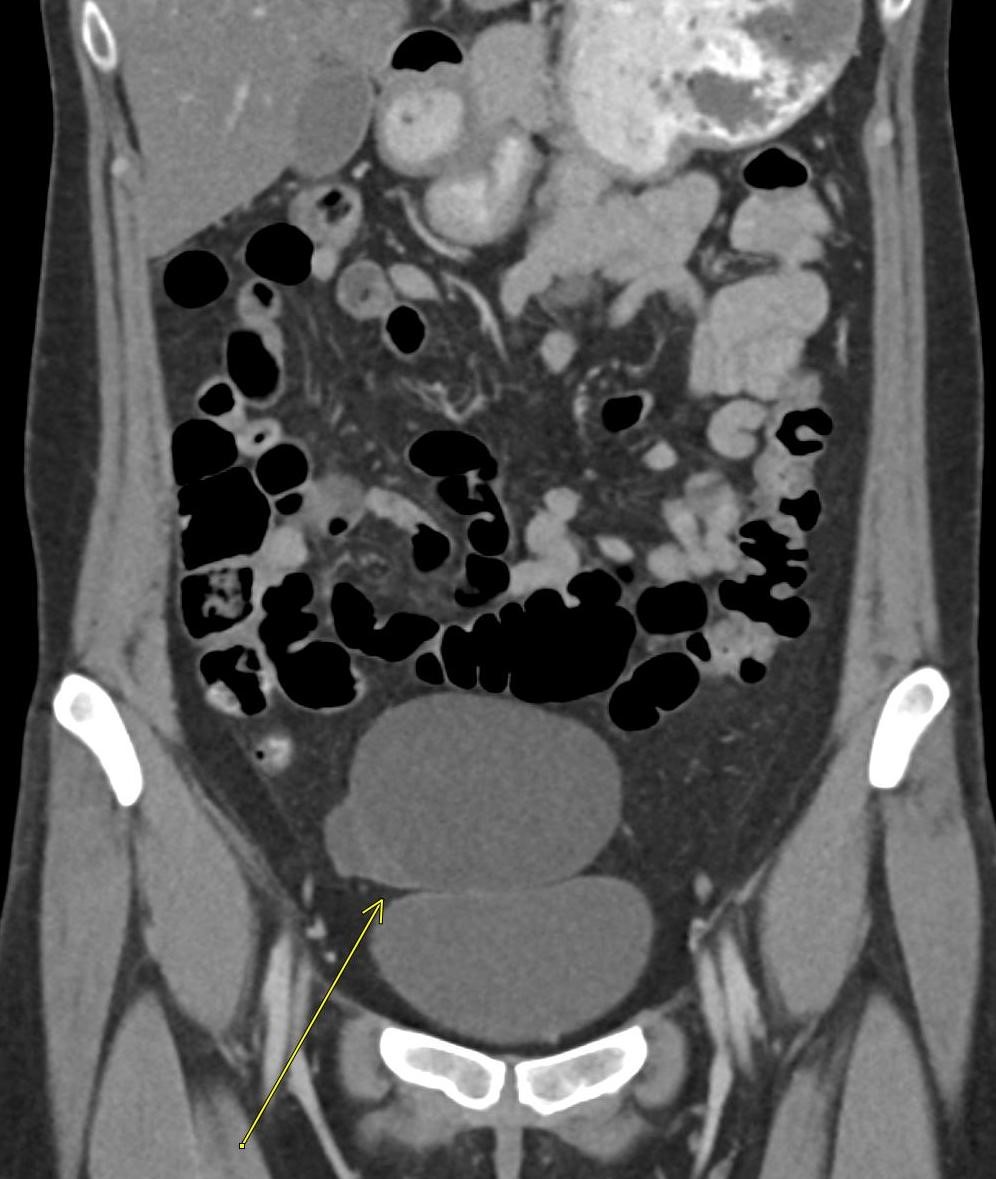

Findings:

A CT of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast was obtained, demonstrating dilatation of the distal appendix to 15 mm (blue arrow) with extensive fat stranding in the right hemiabdomen. The intraperitoneal component of the lumboperitoneal shunt is seen traversing through the inflamed abdomen with a peripherally enhancing fluid collection encasing a portion of the catheter (green arrow). No obvious abnormality is seen regarding the intraspinal portion of the catheter. Small bowel loops in the right hemiabdomen demonstrate reactive wall thickening (yellow arrow), and several prominent reactive mesenteric lymph nodes are also seen.

Diagnosis: Perforated acute appendicitis complicated by an abscess encasing the peritoneal catheter.

Hospital Course: The patient was taken urgently to the operative room for combined surgery with neurosurgery and general surgery. Purulence was noted within the abdomen during laparoscopy and the intraperitoneal portion of the lumboperitoneal shunt was explanted. The appendix appeared inflamed and thus laparoscopic appendectomy was performed. The appendix was sent for surgical pathology, which confirmed the diagnosis of perforated appendicitis. The patient had an unremarkable post-operative course and was discharged home with a short course of oral antibiotics. The lumboperitoneal shunt catheter had been turned off for several years prior to presentation and no revision or replacement was needed per the evaluation of neurosurgery.

Discussion: Acute appendicitis is inflammation of the appendix secondary to obstruction of its lumen resulting in bacterial proliferation. It most commonly occurs between the ages of 10 and 40. Perforation is a feared complication of appendicitis as it can result in abscess formation and peritonitis. Appendectomy is the gold standard for treatment in the United States. Severe cases of appendicitis may necessitate conversion to ileocecectomy or right hemicolectomy based on the intra-operative findings. Appendiceal malignancy can mimic the imaging and intra-operative appearance of acute appendicitis, requiring pathologic confirmation of the diagnosis after appendectomy.

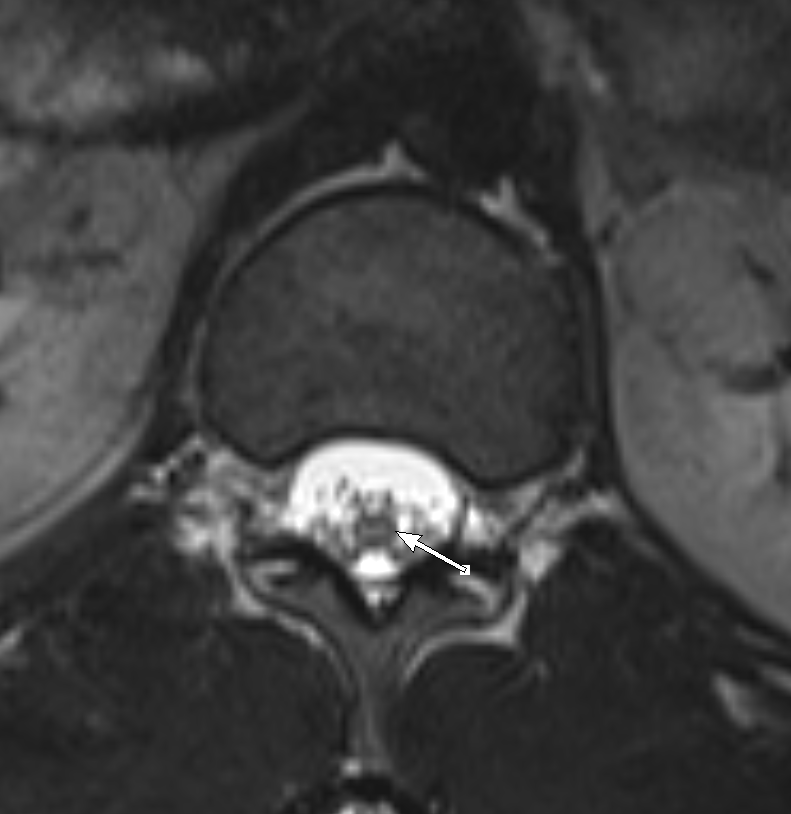

June 2023: Discitis-Osteomyelitis

History: A 50-year-old female presented to the Emergency Department with right lower quadrant pain. A contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis was performed, revealing suspicious findings in the lumbar spine, which prompted further evaluation with contrast-enhanced MRI of the lumbar spine.

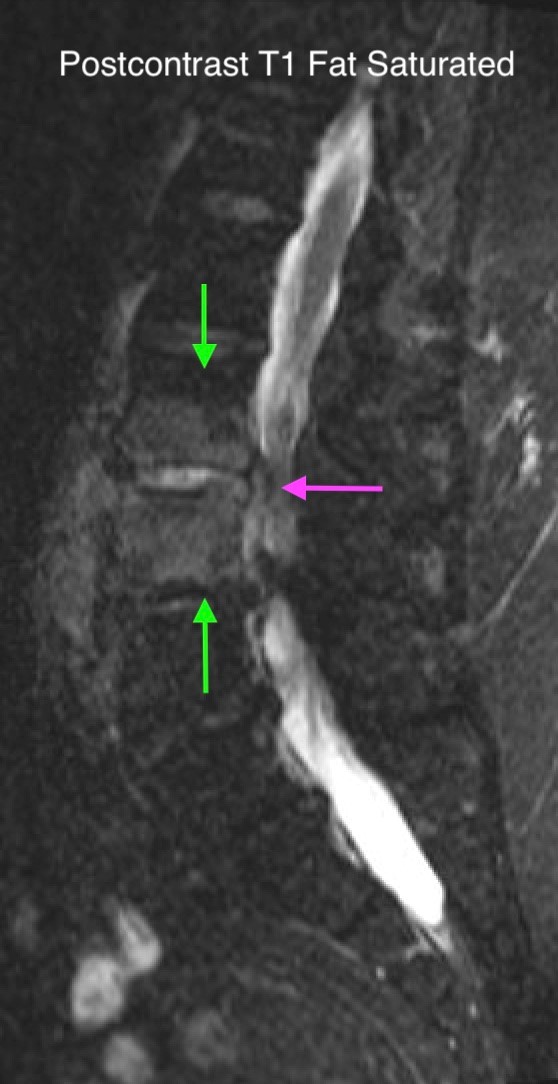

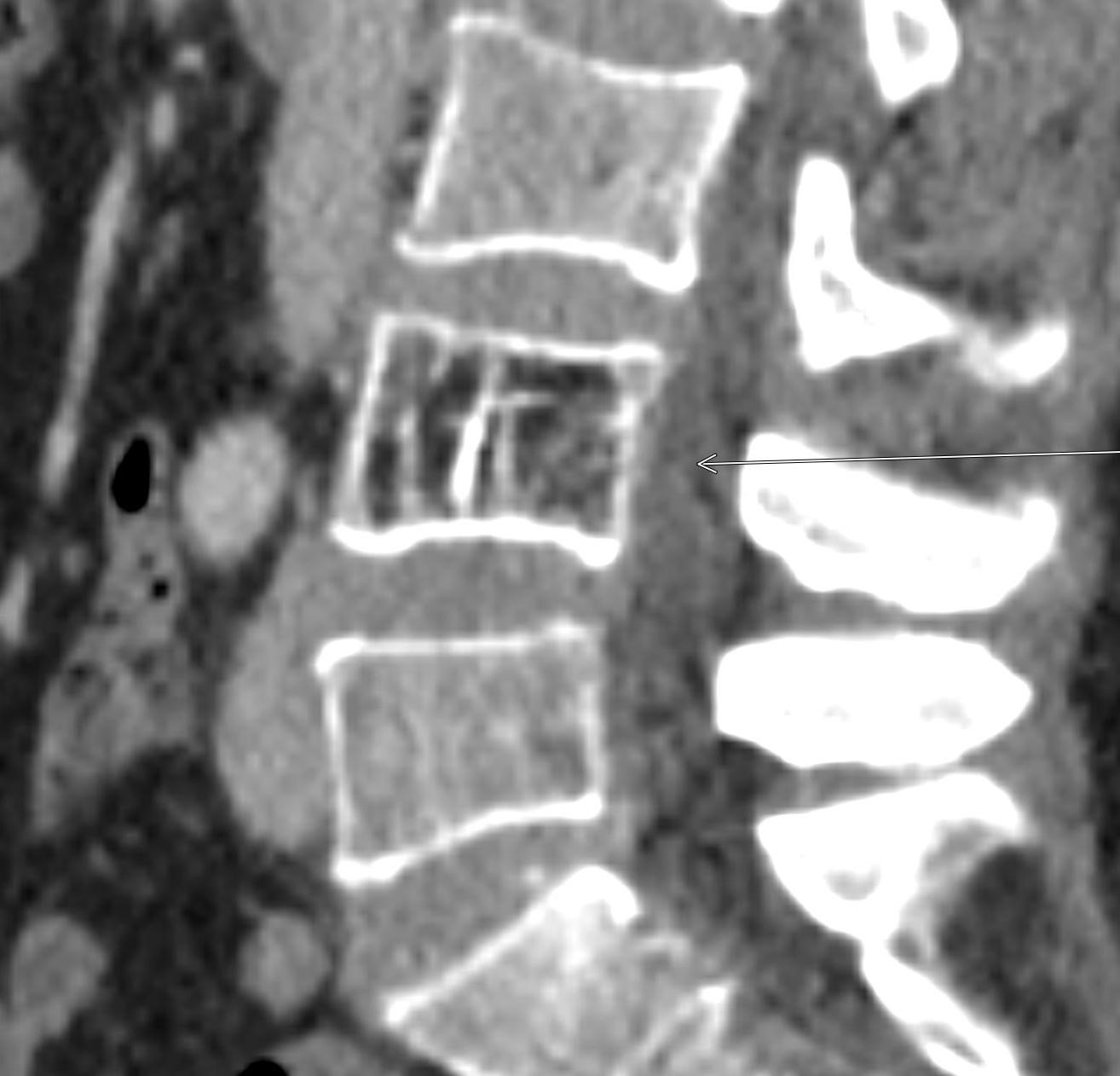

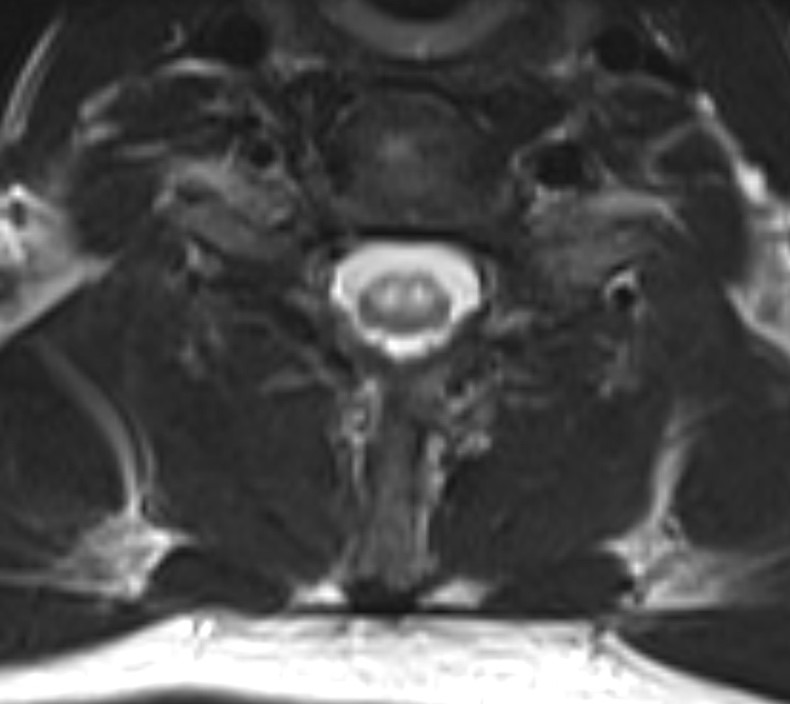

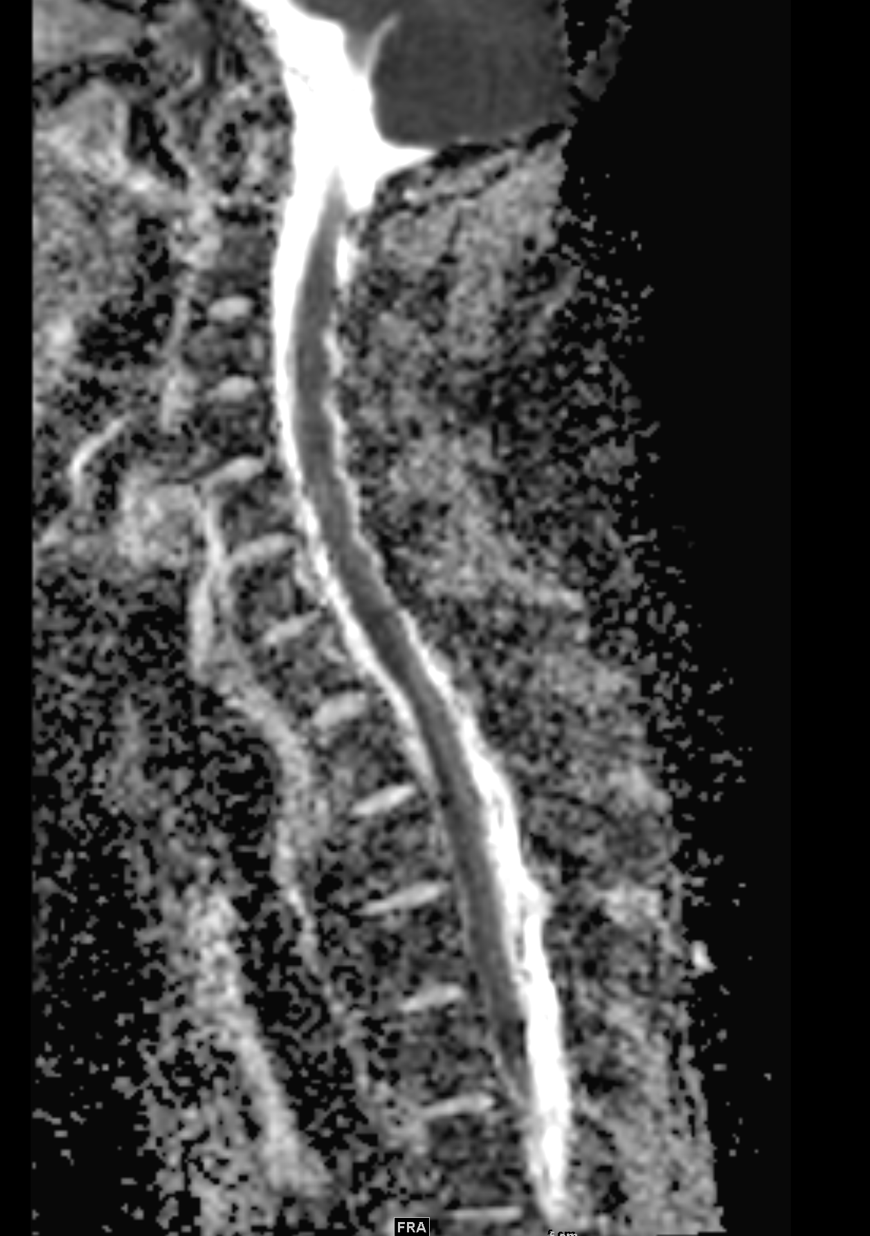

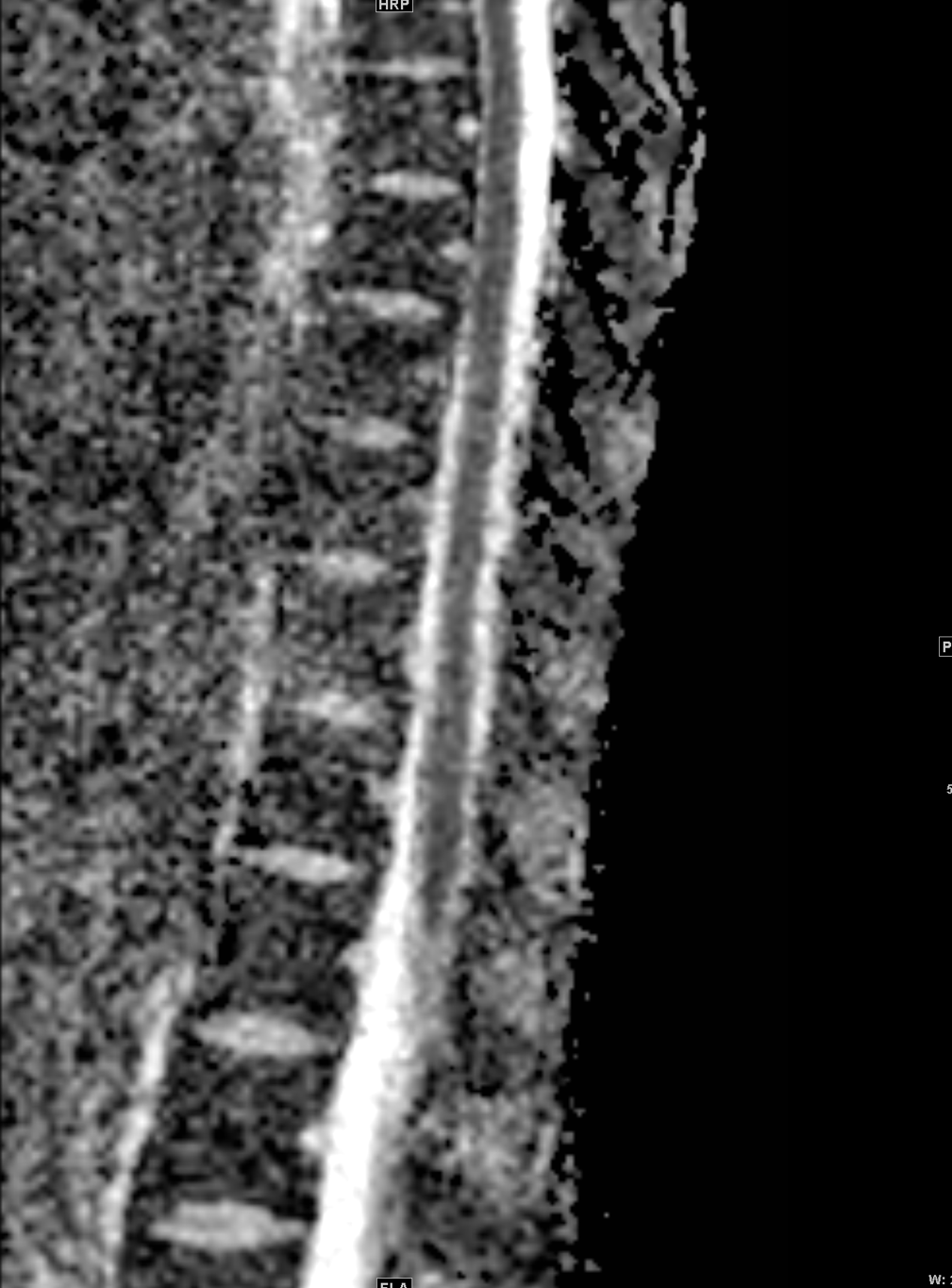

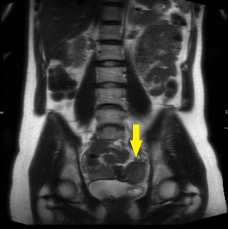

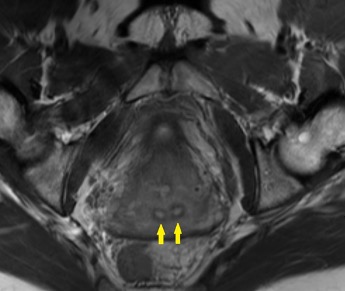

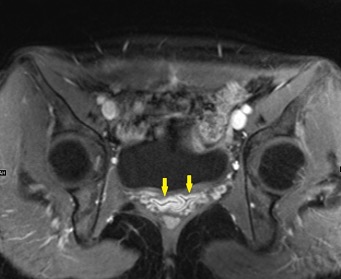

Findings:

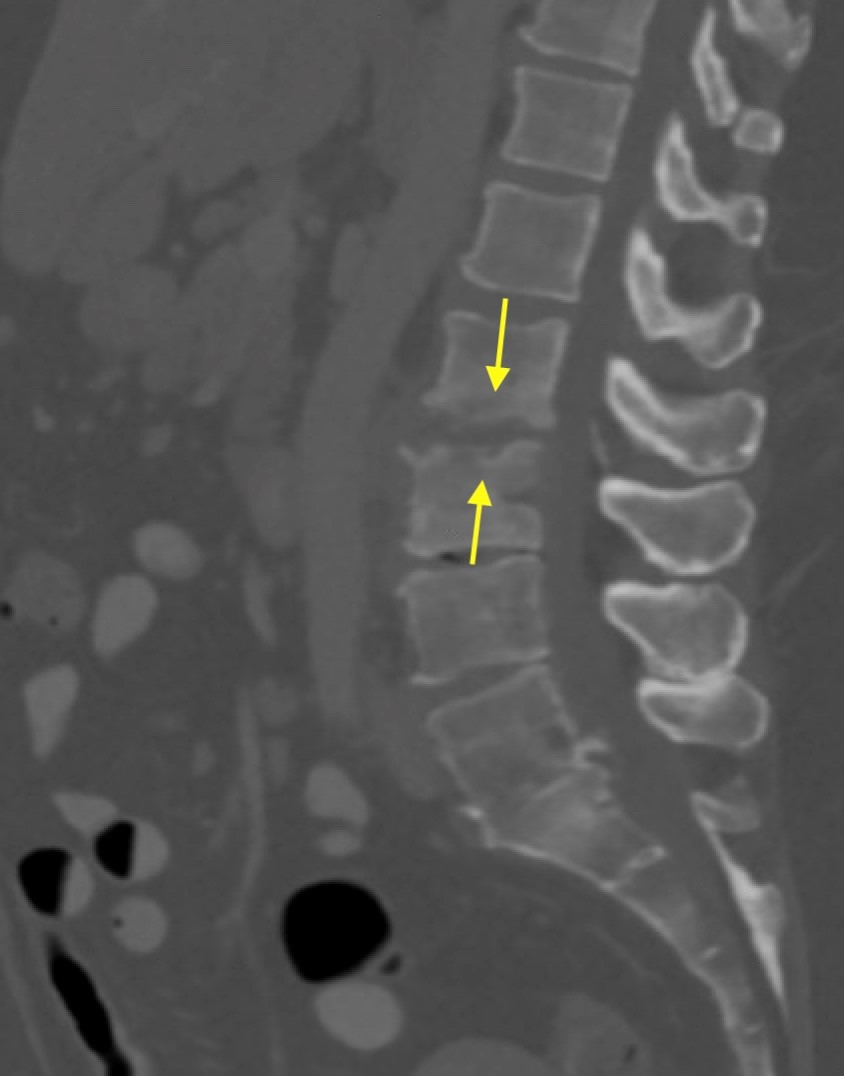

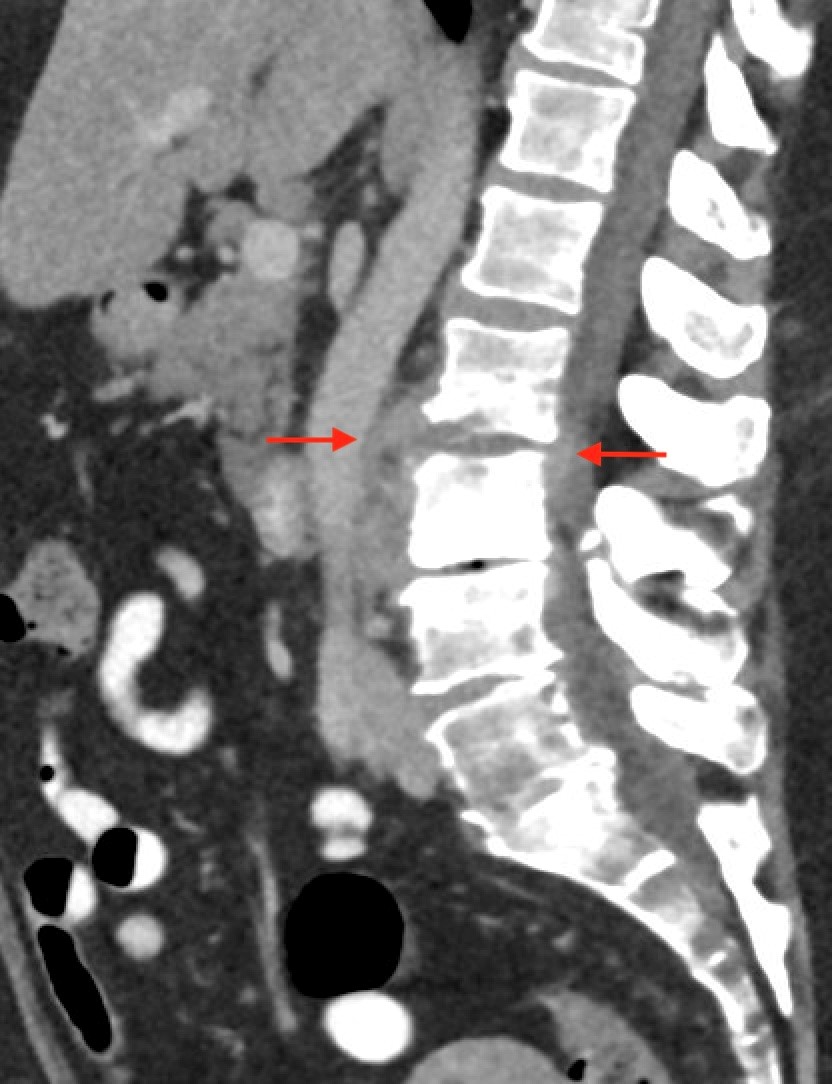

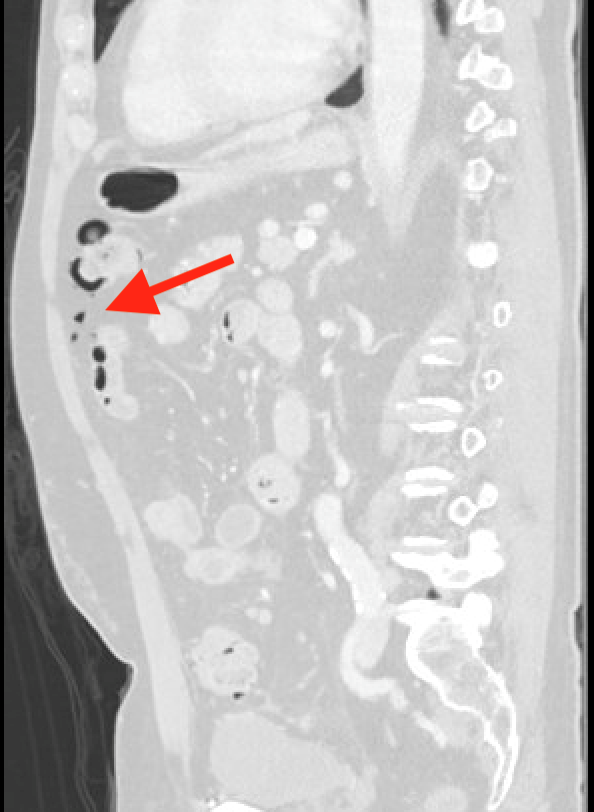

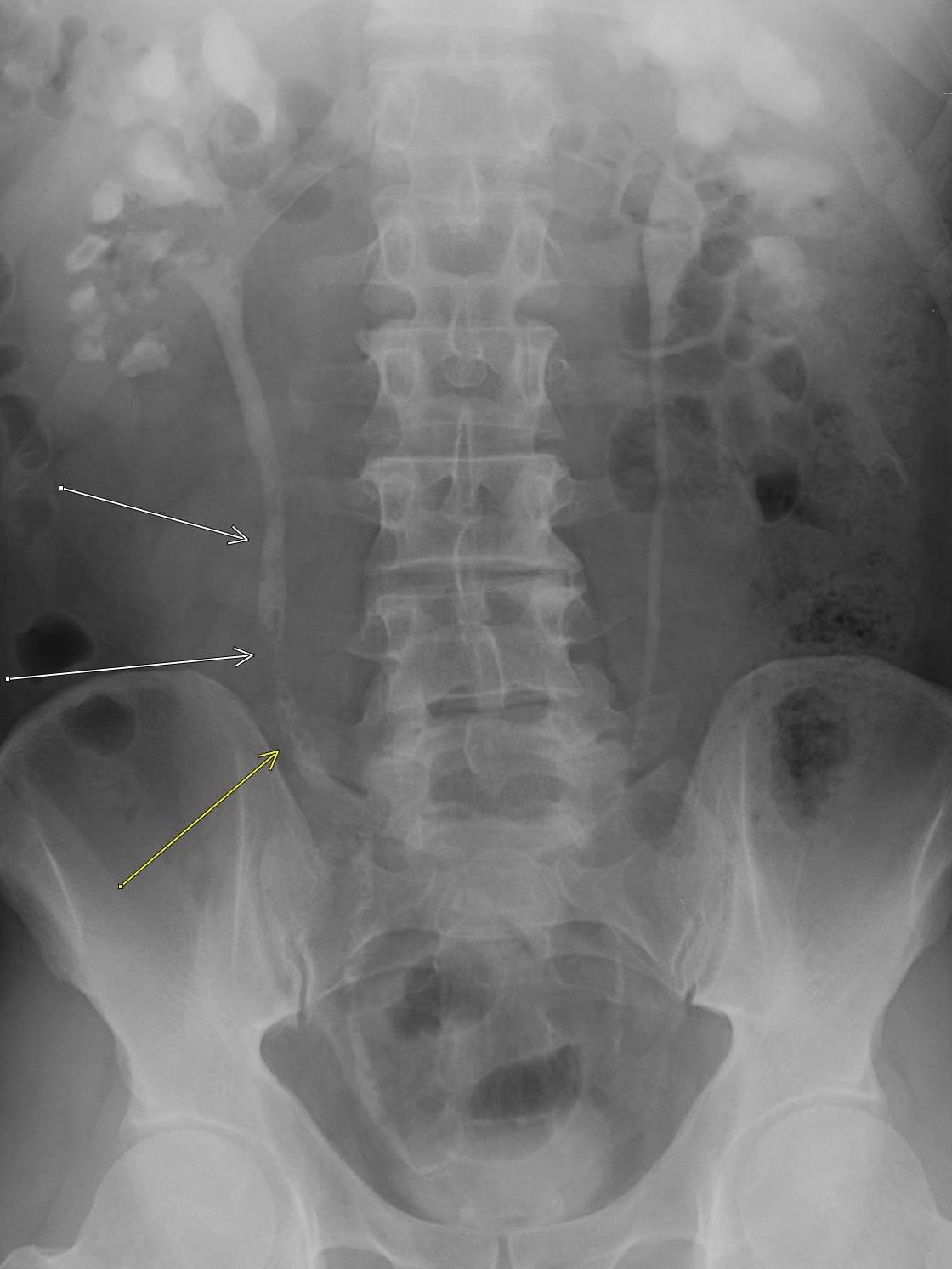

Shown above, sagittal post-contrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis in bone window demonstrates cortical erosions of the inferior endplate of the L2 vertebral body and the superior endplate of the L3 vertebral body (yellow arrows). Soft tissue window on the same study highlights associated prevertebral heterogeneous soft tissue at this level; soft tissue also extends into the ventral epidural space at the L2-3 level (red arrows).

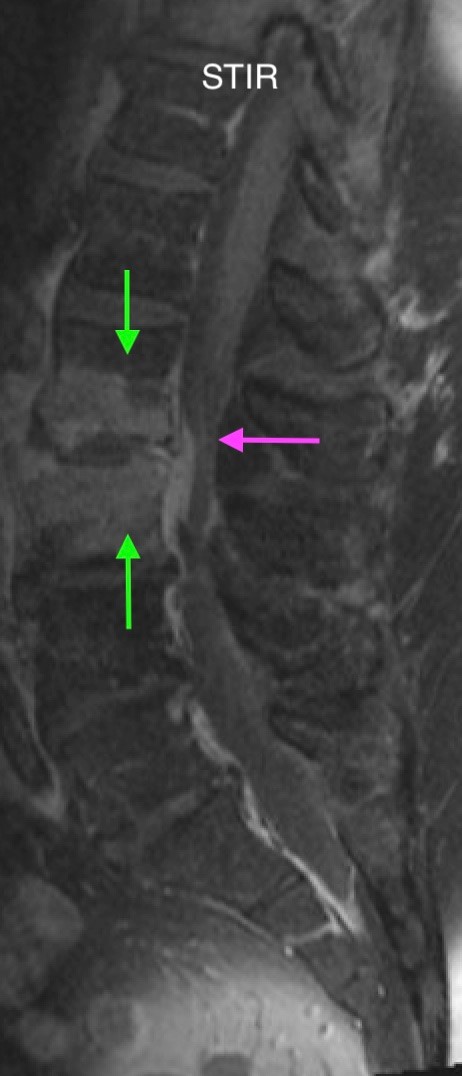

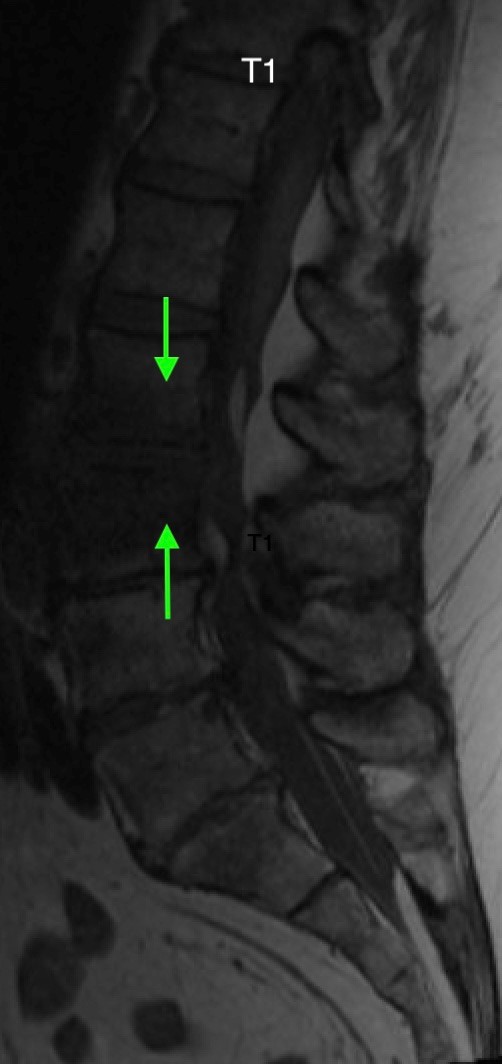

Heterogeneous STIR hyperintense signal is present in the L2-3 disc space and extends to the inferior endplate of the L2 vertebral body and the superior endplate of the L3 vertebral body (green arrows). Comparison between T1 and T1 postcontrast fat saturated images demonstrates associated heterogeneous enhancement in these regions (green arrows). STIR hyperintensity and enhancement extends along the ventral epidural space at the L2-3 level consistent with an epidural phlegmon (purple arrows).

No abnormal cord signal is identified in the distal cord or conus. The above findings are superimposed upon multilevel degenerative changes which altogether result in up to severe spinal canal stenosis at the L2-3 level.

Diagnosis: Discitis-Osteomyelitis

Teaching Points:

Discitis-osteomyelitis is the infection of vertebrae and associated intervertebral discs. Risk factors include immunocompromised state, IV drug use, and diabetes. In adults, it often occurs through hematogenous bacterial seeding of vertebral bodies, which are particularly susceptible due to their slow arterial inflow. Infection then readily spreads to adjacent avascular discs. Patients present with back or neck pain as well as fevers, although inconsistently.

Changes from discitis-osteomyelitis are often not apparent on plain radiographs up until six weeks. Contrast-enhanced MRI is the modality of choice in diagnosis, in part because it delineates extent of spinal canal involvement. T1-weighted images demonstrate low signal intensity involving the affected vertebral endplates and bodies, while T2-weighted images demonstrate corresponding high signal intensity. Fluid signal is identified in the intervertebral disc. Post-contrast imaging demonstrates homogeneous, patchy, or peripheral enhancement in the affected disc and diffuse enhancement in the affected bone marrow. Associated paravertebral and epidural phlegmon or abscess are characterized by heterogenous signal intensity on T1 and T2-weighted sequences, typically hypointense signal on T1-weighted images and hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images. Post-contrast imaging demonstrates diffuse/rim-like enhancement in the paravertebral and epidural soft tissues.

The utility of CT in the diagnosis of discitis-osteomyelitis is limited. CT may not reveal early destructive vertebral endplate changes and cannot reliably demonstrate extent of spinal canal involvement. However, it may help demonstrate associated adjacent soft tissue masses and abscesses, as in the above case.

Important differential considerations include degenerative endplate disease and neuropathic joint changes. Unlike discitis-osteomyelitis, degenerative changes do not show high signal intensity of the disc on T2-weighted images; there is also no soft tissue involvement. There may be associated vacuum phenomenon. Neuropathic joint changes may include joint debris, spondylolisthesis, lower signal intensity of disc/marrow on T2-weighted images, paraspinal masses related to inadequately healed fractures, and vacuum phenomenon.

Most patients with discitis-osteomyelitis are treated with six weeks of systemic antimicrobials, while others require surgery due to factors such as cord compression or inadequate response to antibiotics. Follow-up MRI is generally not indicated, as imaging findings can lag behind clinical improvement by 4-6 weeks.

References:

An HS, Seldomridge JA. Spinal Infections. Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research. 2006;444:27-33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.blo.0000203452.36522.97

Babic M, Simpfendorfer CS. Infections of the Spine. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 2017;31(2):279-297. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idc.2017.01.003

Hong SH, Choi JY, Lee JW, Kim NR, Choi JA, Kang HS. MR Imaging Assessment of the Spine: Infection or an Imitation? RadioGraphics. 2009;29(2):599-612. doi:https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.292085137

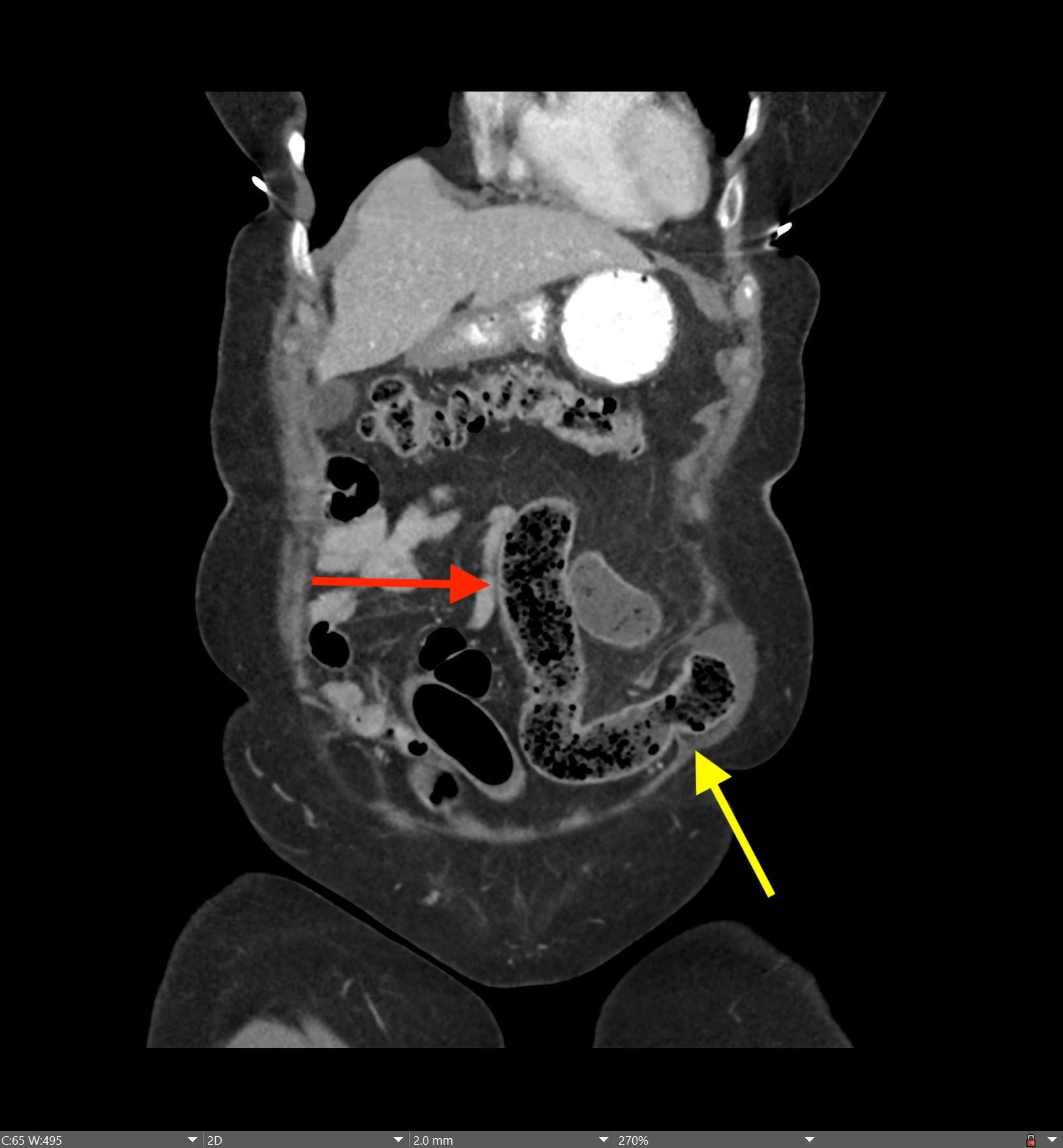

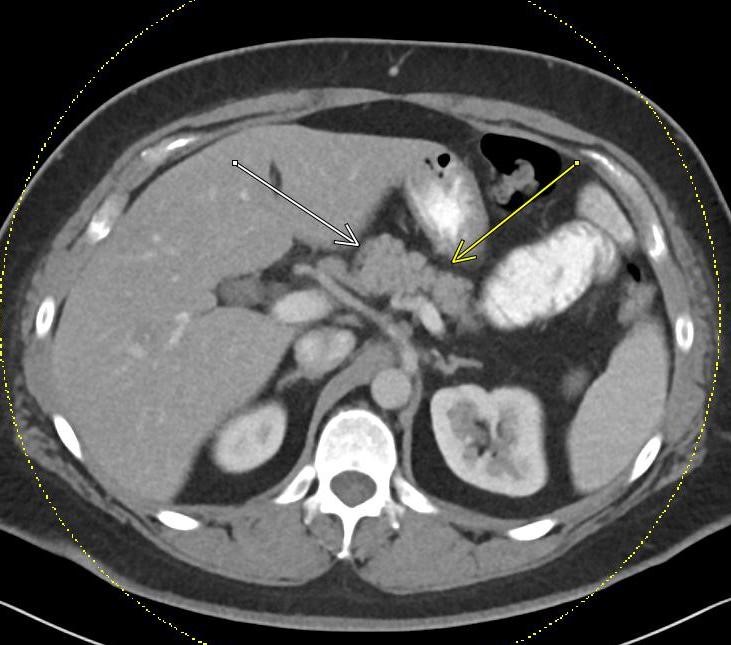

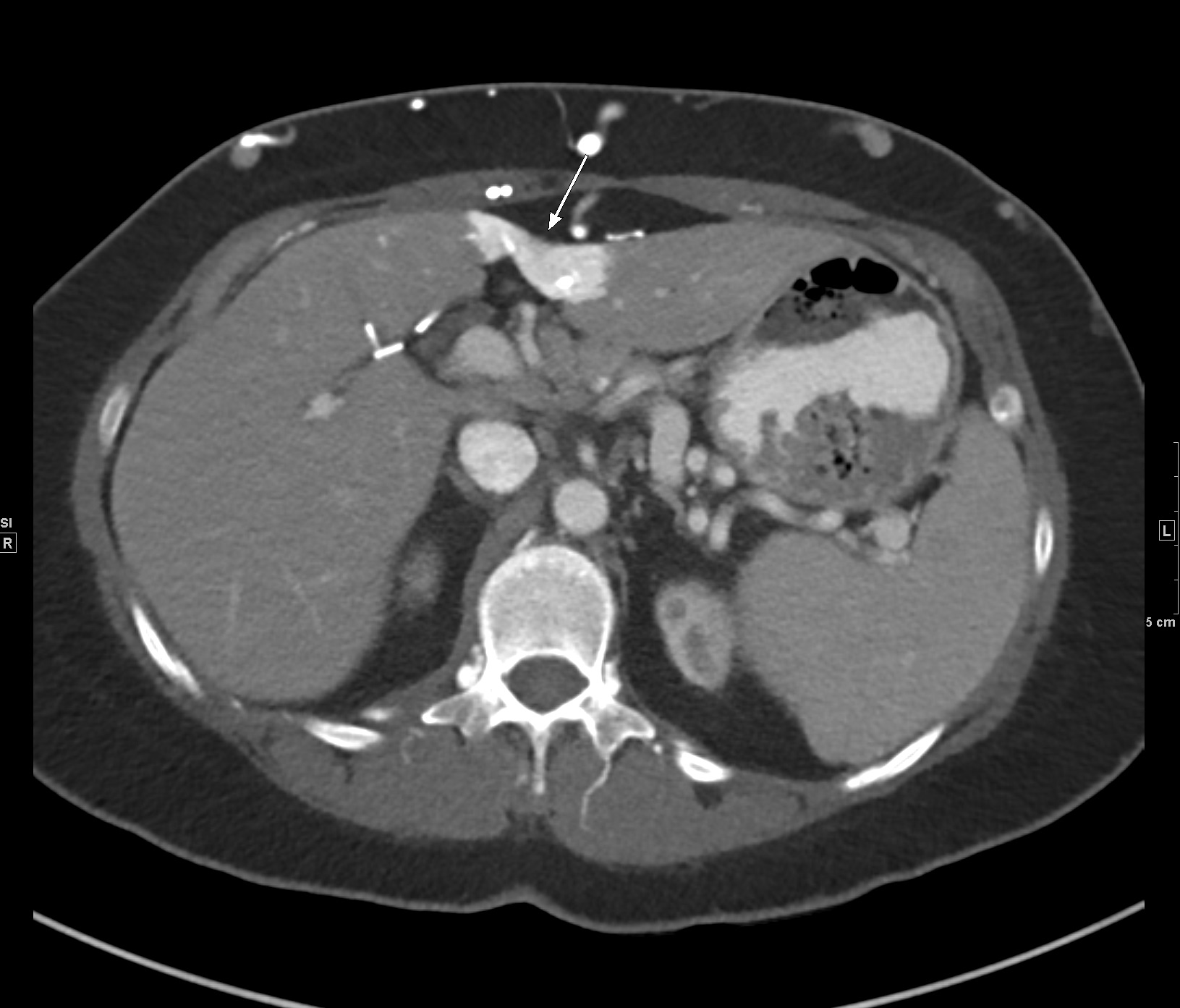

May 2023: Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis with Venous Thrombosis

History: A 30-year-old male presented to the Emergency Department with one week of left-sided abdominal pain radiating to the back and epigastrium. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast was obtained for further evaluation.

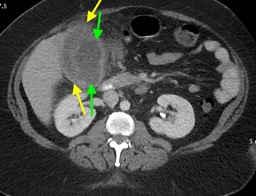

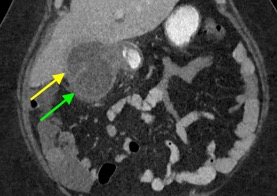

Findings:

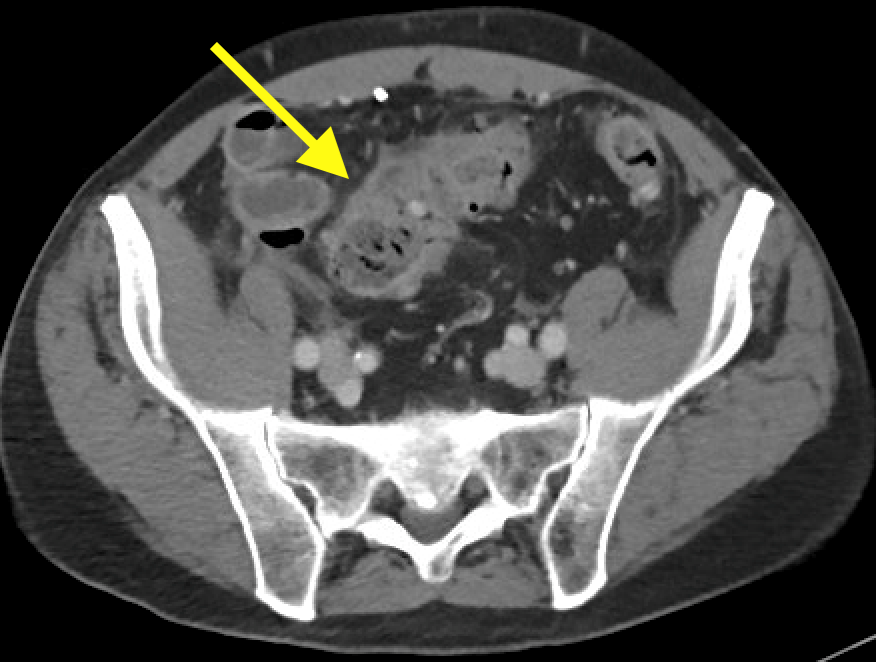

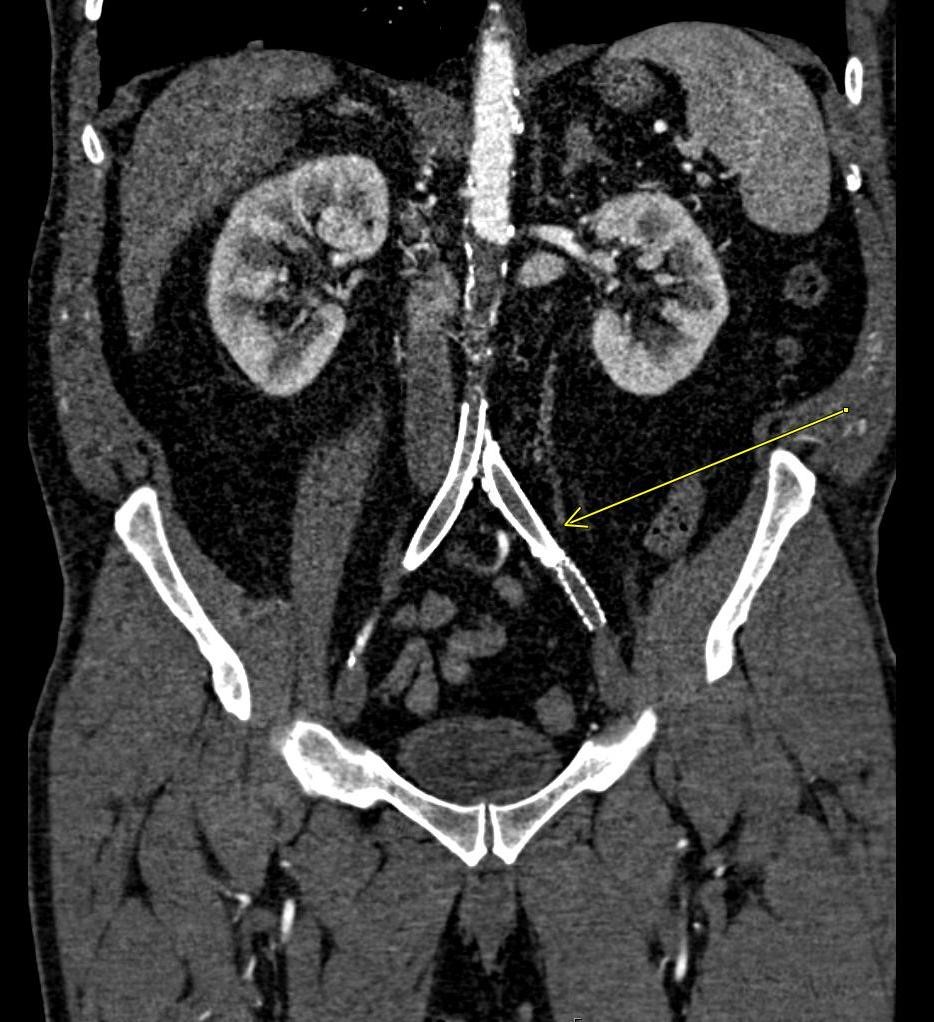

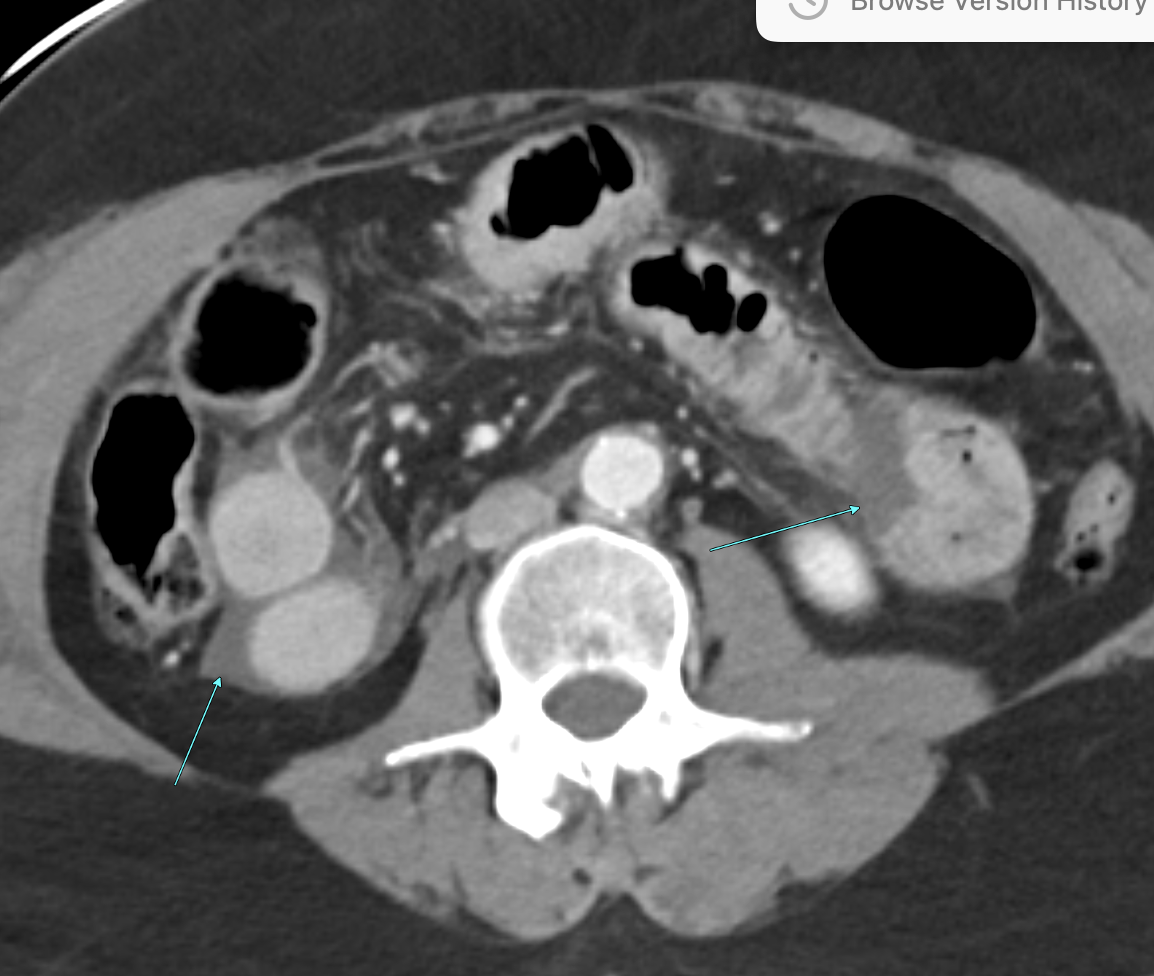

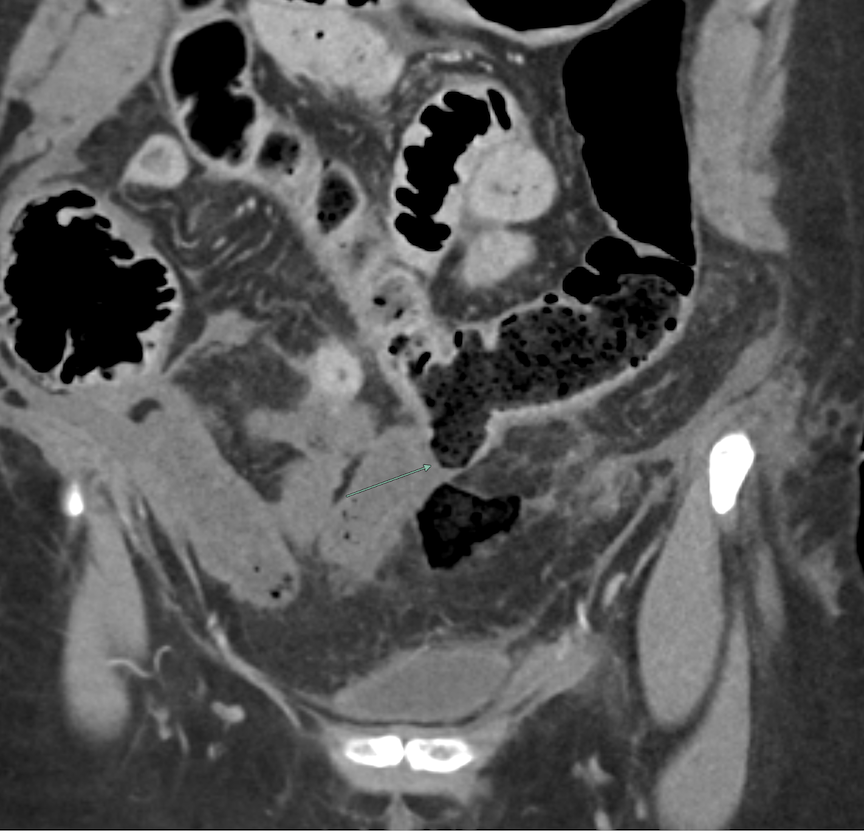

Contrast-enhanced axial and coronal images of the abdomen at the level of the pancreas demonstrate loculated fluid with associated peripancreatic stranding near the pancreatic tail (yellow arrow) and focal hypoenhancement in the uncinate process (green arrow). The splenic vein is thrombosed along its entire course, and focal hypoattenuation in the anterior main portal vein represents a small nonocclusive thrombus (red arrows).

Diagnosis: Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis with Venous Thrombosis

Teaching Points:

The two subtypes of acute pancreatitis are interstitial edematous pancreatitis and necrotizing pancreatitis. Necrotizing pancreatitis comprises a smaller proportion of cases, but is characterized by worse severity of disease. There is significant mortality associated with acute necrotizing pancreatitis, ranging from 2-39%. Pancreatitis can be diagnosed when there are at least two of three of the following manifestations: characteristic abdominal pain, a three-fold increase in serum lipase or amylase, and characteristic radiological findings.

CT is considered the most useful imaging modality in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Typical features include pancreatic parenchymal enlargement, peripancreatic fat stranding, and associated fluid collections.

According to the 2012 revised Atlanta classification system, there are three subtypes of necrotizing pancreatitis depending on the location of the necrosis: parenchymal, peripancreatic, and combined. Normal pancreatic parenchyma maximally enhances approximately 40 seconds after intravenous contrast injection. Parenchymal necrosis is suggested by focal pancreatic attenuation less than 30 Hounsfield Units. The severity of inflammation depends on the extent of parenchymal involvement. Although often difficult to diagnose on CT, peripancreatic necrosis may be characterized by linear peripancreatic stranding. Initially, this can resemble acute interstitial edematous pancreatitis, but increasing heterogeneity makes the diagnosis more definitive after 1 week.

Important complications of necrotizing pancreatitis include infection, mass effect, biliary obstruction, pancreatic duct strictures and disconnection, arterial pseudoaneurysms, hemorrhage, fluid collections (acute necrotic collections and walled-off necrosis, which are beyond the limits of this discussion), and venous thrombosis. As demonstrated in the case above, venous thrombosis is characterized by nonenhancement within a venous structure. The splenic vein is most commonly affected, although the superior mesenteric vein and portal veins may also be involved.

Treatment of acute necrotizing pancreatitis is largely comprised of fluids and nutritional support. Some patients require admission to the intensive care unit. Surgical necrosectomy is sometimes performed, although there are several minimally invasive techniques that are also used today, including imaging-guided percutaneous techniques and endoscopic methods.

References:

Shyu JY, Sainani NI, Sahni VA, et al. Necrotizing Pancreatitis: Diagnosis, Imaging, and Intervention. RadioGraphics. 2014;34(5):1218-1239. doi:https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.345130012

April 2023: Parathyroid Adenoma

History: A 65-year-old female presented to her primary care office with hypercalcemia and elevated parathyroid hormone. A nuclear medicine parathyroid scan was ordered for further evaluation.

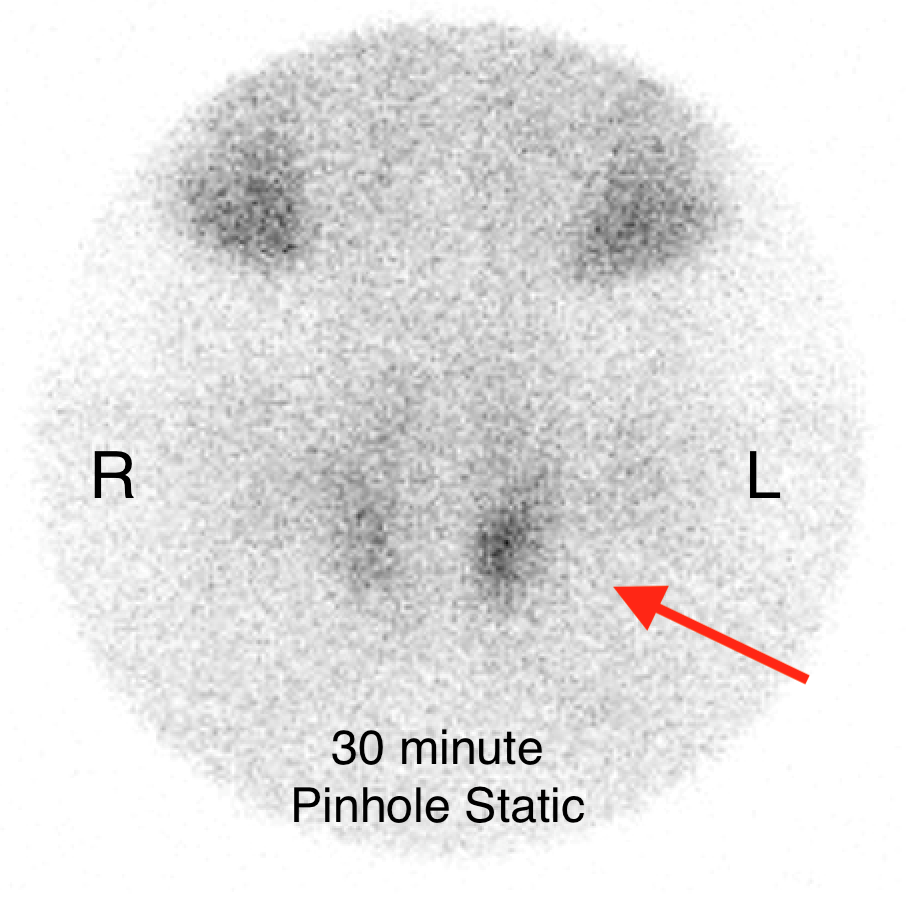

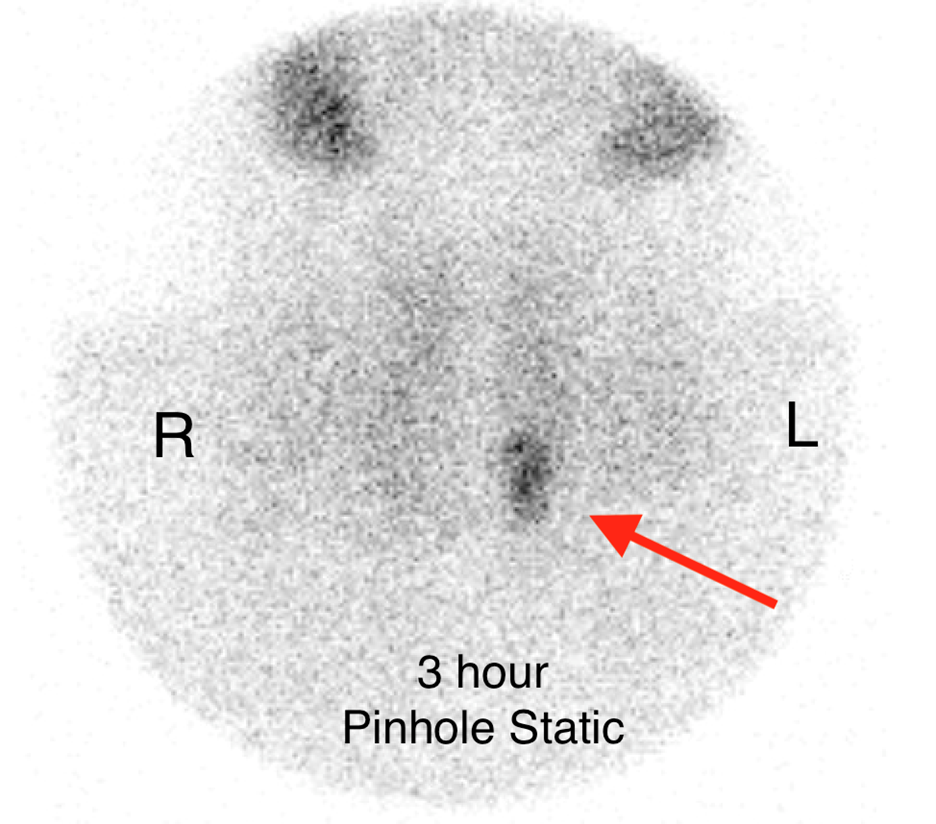

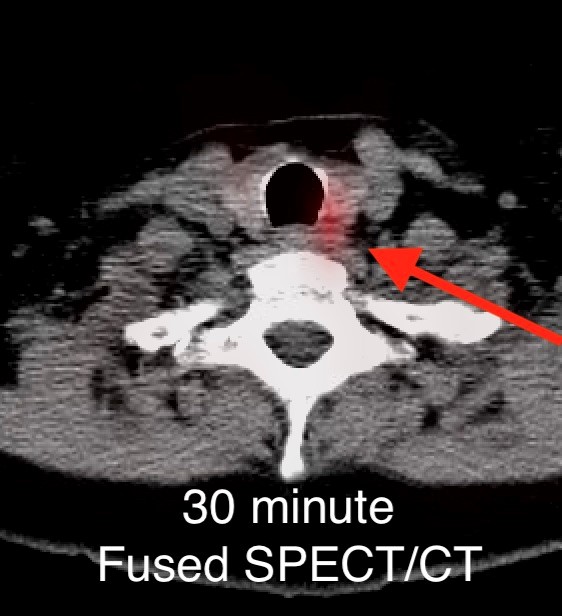

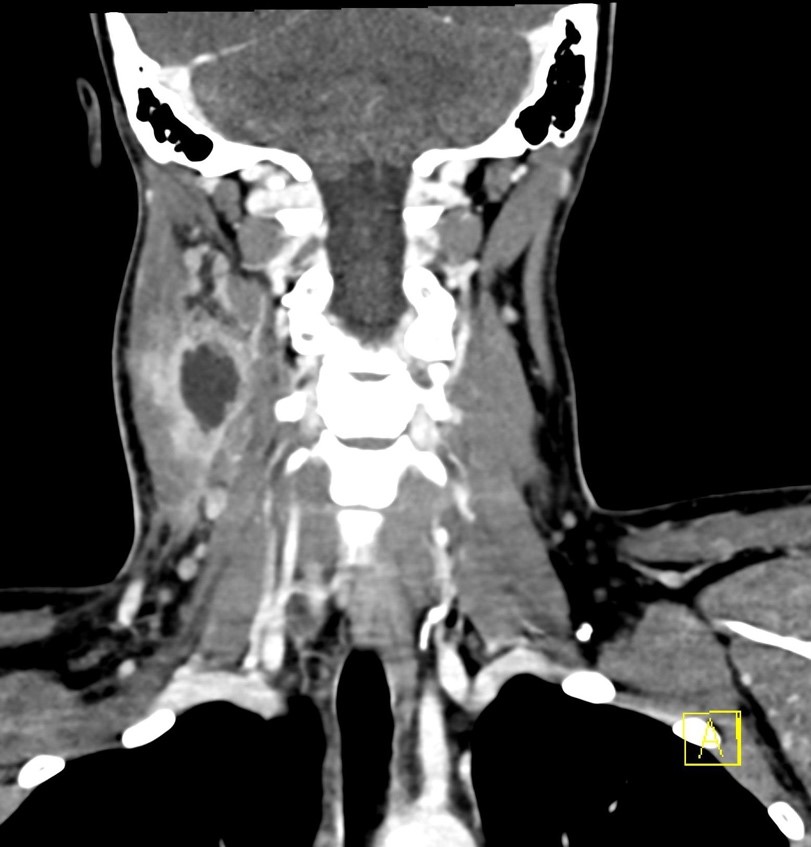

Findings:

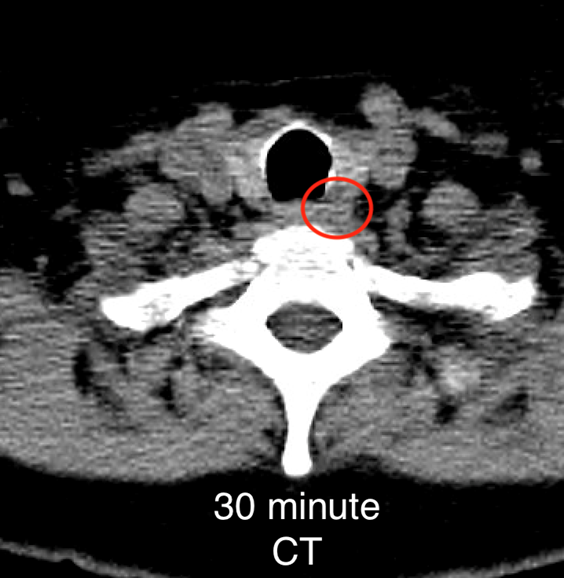

The institutional protocol for nuclear medicine parathyroid scan was followed. As seen below on the pinhole images acquired at 30 minutes, there is physiologic uptake of the radiopharmaceutical in the thyroid gland with a focal area of marked uptake in the inferior left neck (red arrow).

On the 3 hour delayed images, there is washout of the radiotracer from the thyroid gland with a persistent focal area of marked radiotracer uptake in the inferior left neck (red arrow). This corresponds to a nodule posterior to the inferior left thyroid lobe on the fused axial SPECT/CT (red arrow) and CT images (red circle) acquired at 30 minutes.

Diagnosis: Parathyroid Adenoma

Teaching Points:

Most cases of primary hyperparathyroidism are due to parathyroid adenomas, or tumors of the parathyroid gland. The initial diagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism is made upon laboratory evaluation. However, imaging is crucial in determining surgical management.

A commonly used technique for diagnosing parathyroid adenomas is Tc-99m sestamibi parathyroid scintigraphy. For this exam, the patient is injected with Tc-99m-labeled sestamibi radiotracer. Planar images of the neck/mediastinum are acquired 10-30 minutes after injection followed by another set of planar images 90-180 minutes after injection. Radiotracer is initially taken up by both the thyroid gland and parathyroid glands. However, it washes out of most parathyroid adenomas slower than normal thyroid/parathyroid tissue. As in the case above, 10-30 minute images demonstrate a focus of discrete uptake. This focuso of uptake progressively increases on 90-180 minute images. Some institutional protocols also include SPECT or SPECT/CT imaging to help localize lesions.

Another nuclear medicine technique utilizes both Tc-99m sestamibi and an additional radiotracer that accumulates only in the thyroid gland, such as iodine-123 (I-123) or Tc-99m pertechnetate. I-123/Tc-99m pertechnetate images define the thyroid gland, which can then be subtracted from the Tc-99m sestamibi images to determine areas of abnormal parathyroid activity.

Other important techniques that are used to diagnose parathyroid adenomas include ultrasound and 4D-CT, beyond the scope of this discussion.

Nuclear medicine scans prove particularly useful in identifying ectopically located parathyroid adenomas in the neck/mediastinum. They are also generally operator independent. Without concomitant CT, however, these exams are quite limited in providing anatomic data. An important consideration in interpretation is that some adenomas do not follow the typical washout characteristics described above. Furthermore, various other pathologies can result in false positives, including thyroid nodules/carcinomas, other cancers, and Graves’ disease.

Imaging helps identify the presence/absence of parathyroid adenomas. Generally, parathyroid adenomas are amenable to minimally invasive thyroidectomy, unlike multiglandular or non-localizing disease, which may call for bilateral neck exploration. Minimally invasive thyroidectomy is associated with lower morbidity and complications than bilateral neck exploration.

References:

Bunch PM, Kelly HR. Preoperative Imaging Techniques in Primary Hyperparathyroidism. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 2018;144(10):929. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2018.1671

Zarei A, Karthik S, Chowdhury FU, Patel CN, Scarsbrook AF, Vaidyanathan S. Multimodality imaging in primary hyperparathyroidism. Clinical Radiology. 2022;77(6):e401-e416. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2022.02.018

March 2023: Pyosalpinx/Tubo-ovarian abscess

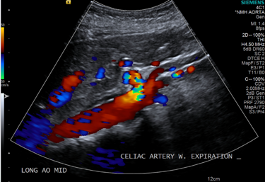

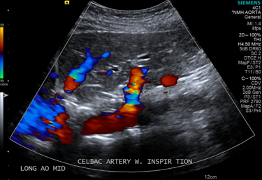

History: A 30-year-old female presented to the Emergency Department with two weeks of lower abdominal pain. A contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis was performed, followed by pelvic ultrasound.

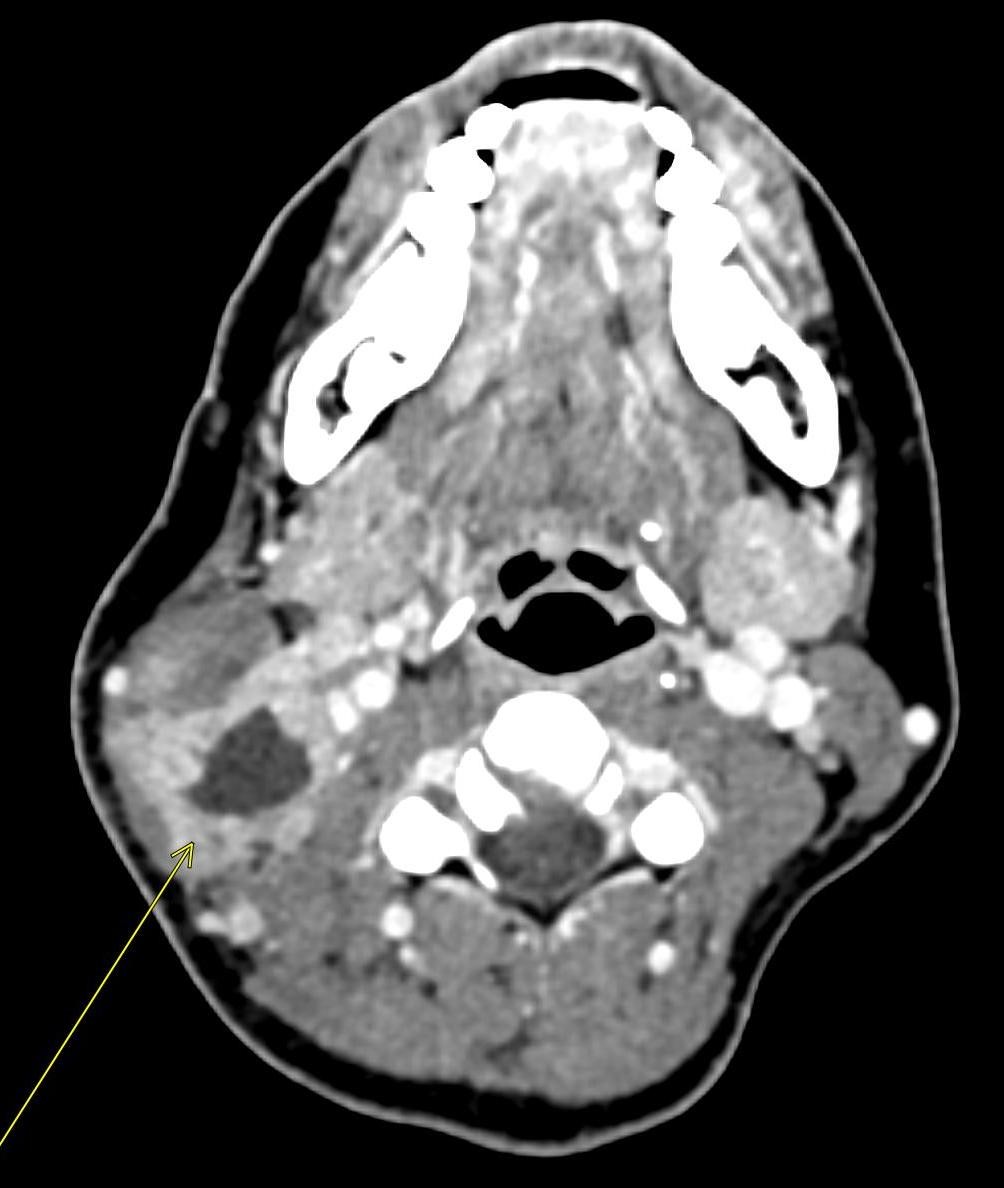

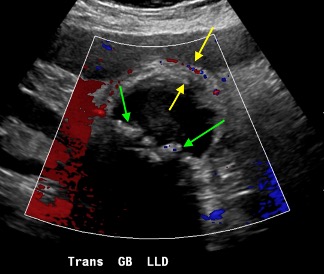

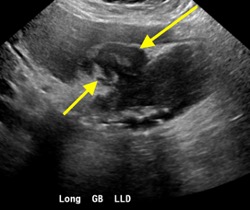

Findings:

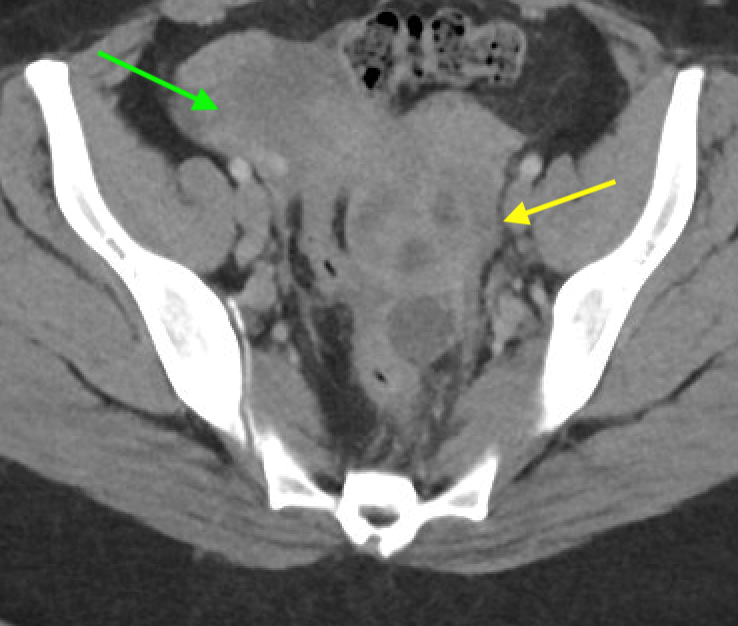

Axial and coronal contrast-enhanced images of the pelvis demonstrate a complex, multiloculated, elongated, fluid-filled tubular structure in the left adnexal region with associated wall thickening and mural enhancement (yellow arrows). The structure abuts the uterus and is associated with surrounding fat stranding. A thick-walled cystic structure is identified in the right ovary (green arrow).

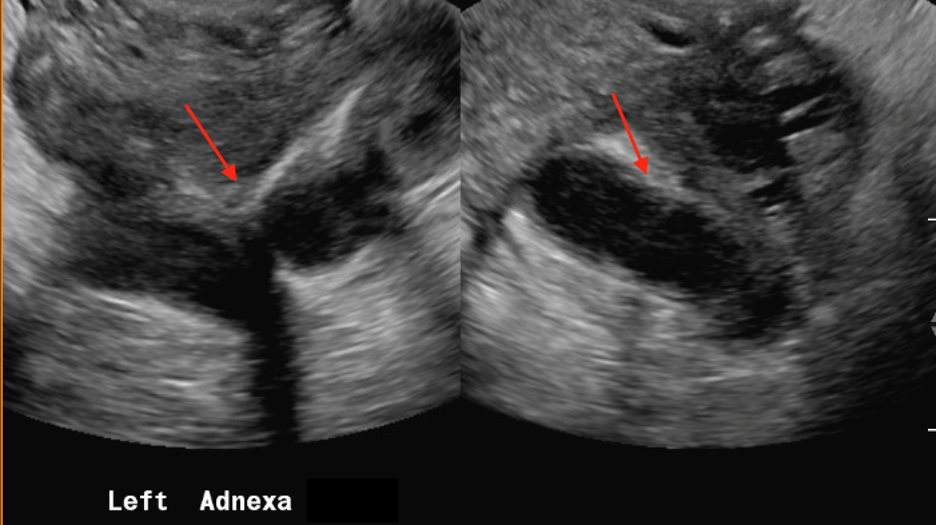

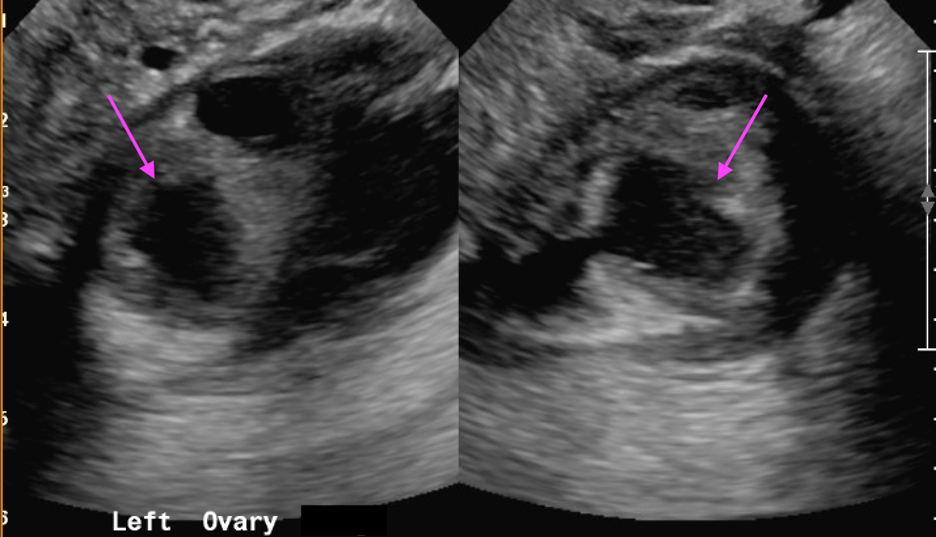

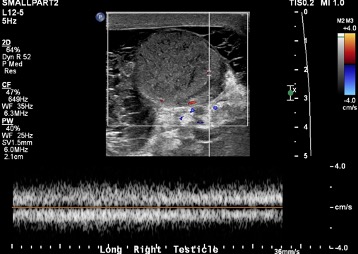

Follow-up pelvic ultrasound of the left adnexa demonstrates a complex left tubular structure (red arrows) and a left ovary containing a few complex cystic structures (see purple arrows, for example). Similar findings are noted in the right adnexa (not shown).

Diagnosis: Pyosalpinx/Tubo-ovarian abscess

Teaching Points:

Pyosalpinx and tubo-ovarian abscess are part of a spectrum of disease known as pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). PID is an ascending infection of the female genital tract often caused by sexually transmitted diseases. Risk factors including multiple sexual partners, gynecological surgery, and existing intrauterine device, amongst others. It can manifest as salpingitis, pyosalpinx, and tubo-ovarian complex/abscess (in order of progression). Some patients are asymptomatic, while others present with symptoms such as pelvic pain or vaginal discharge. Broadly, ultrasound is the best modality to evaluate female pelvic pathology, including PID.

Salpingitis is the earliest stage of PID. Sonographic findings may include thickening of the fallopian tube and mural hyperemia upon color Doppler assessment, although ultrasound can often be negative as well. CT/MRI may demonstrate fallopian tube mural thickening and mucosal enhancement. Associated free fluid may be seen.

Pyosalpinx occurs when pus accumulates in the fallopian tubes. As in the above case, ultrasound demonstrates debris-filled, dilated fallopian tubes characterized by low-amplitude echoes. Doppler assessment reveals mural hyperemia of the fallopian tubes. CT demonstrates a tubular mass-like structure adjacent to the uterus. Surrounding inflammatory change supports the diagnosis. On MRI, findings include dilated fallopian tubes with high signal intensity on T2-weighed imaging. Depending on the protein content of the fallopian tubes, T1-weighted imaging may demonstrate varying intraluminal signal.

Tubo-ovarian abscess occurs when infection involves the ovaries and peritoneal cavity, such that the ovaries and fallopian tubes become indistinguishable. Ultrasound may demonstrate a complex mixed cystic/solid adnexal mass, similar to the above case. MRI demonstrates T2-hyperintense cystic spaces and rim-enhancement of the adnexal mass.

A known complication of PID is Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome, which occurs when infection spreads into the right paracolic gutter and right upper quadrant peritoneal structures. On CT, this manifests as thickening and enhancement of the liver capsule and intrahepatic perfusional variation. Chronic PID is characterized by hydrosalpinx, when there is distension of the fallopian tubes with fluid.

The mainstay of treatment of PID is appropriate antibiotic administration. In the setting of tubo-ovarian abscess, surgical intervention and/or drainage may be necessary.

References:

Chappell CA, wiesenfeld HC. Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management of Severe Pelvic Inflammatory Disease and Tuboovarian Abscess. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012;55(4):893-903. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/grf.0b013e3182714681

Revzin MV, Moshiri M, Katz DS, Pellerito JS, Mankowski Gettle L, Menias CO. Imaging Evaluation of Fallopian Tubes and Related Disease: A Primer for Radiologists. RadioGraphics. 2020;40(5):1473-1501. doi:https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2020200051

Rezvani M, Shaaban AM. Fallopian Tube Disease in the Nonpregnant Patient. RadioGraphics. 2011;31(2):527-548. doi:https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.312105090

February 2023: Appendiceal Mucocele/Mucinous Appendiceal Neoplasm

History: A 70-year-old female presented to the urologist for hematuria. A triphasic CT was performed for further evaluation. An incidental finding was made on this examination.

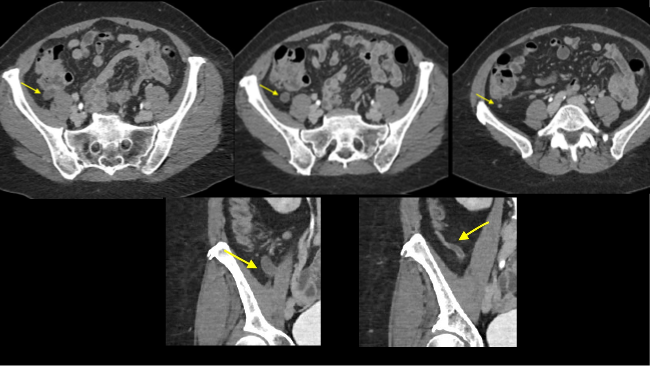

Findings:

Sequential axial images of the lower abdomen progressing from superiorly to inferiorly (left to right in the top row) and sequential coronal images of the right lower quadrant progressing anteriorly to posteriorly (left to right in the bottom row) demonstrate dilatation of the appendix to 1.2 cm at its base with gradual tapering to normal caliber at the appendiceal tip (yellow arrows). The proximal appendix is filled with fluid density material. There is no periappendiceal fat stranding or appendiceal hyperenhancement to suggest appendicitis. Findings raise suspicion for an appendiceal mucocele, with appendiceal neoplasm not excluded. The patient was referred for surgical consultation, prompting laparoscopic appendectomy with partial cecectomy. Final pathology was consistent with a low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (LAMN).

Diagnosis: Appendiceal mucocele/mucinous appendiceal neoplasm

Teaching Points:

The specific histologic diagnosis in the above case, low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (LAMN), belongs to the broad pathologic category of appendiceal mucoceles, which comprises both benign and malignant entities. “Mucocele” refers to an appendix that is filled with mucus. Non-neoplastic etiologies of mucoceles include mucosal hyperplasia and retention cysts. Neoplastic etiologies include mucinous adenoma, low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (LAMN), and mucinous adenocarcinoma. The non-neoplastic etiologies have no potential for metastasis or pseudomyxoma peritonei. Amongst the neoplastic etiologies, mucinous adenoma is typically benign. Meanwhile, LAMN and mucinous adenocarcinoma have the potential to cause pseudomyxoma peritonei as well as hematogenous/nodal metastases. Approximately half of all patients with appendiceal mucoceles are asymptomatic, while the remainder may have a variety of nonspecific presentations. The larger group of epithelial appendiceal neoplasms (including both mucinous and non-mucinous subtypes) are found in the 5th-7th decades of life.

Appendiceal mucoceles are often found on CT. CT typically demonstrates a hypoattenuating tubular structure in the expected region of the appendix, as in the above case. There is usually an enhancing wall of variable thickness. Calcifications are variably present. Surrounding inflammatory changes or abscesses are not seen, excluding appendicitis as a differential diagnosis. MRI typically demonstrates a T2 hyperintense, T1 hypointense mass near the appendix. While both CT and MRI can demonstrate pseudomyxoma peritonei, MRI has better detection by means of diffusion weighted sequences and delayed gadolinium-enhanced T1 fat-saturation. In general, the imaging features cannot predict the risk of malignancy.

Imaging can sometimes reveal an inverted configuration of a mucocele extending into the cecum. Mucoceles infrequently cause small bowel obstructions related to rupture or extrusion of mucin amongst other etiologies. Even more rarely, they can result in intussusception. A potential complication of appendiceal mucoceles is pseudomyxoma peritonei, in which mucin fills the peritoneum and coats the serosa of the organs. This has variable imaging features, including mucinous ascites, peritoneal deposits/implants, and omental caking.

The treatment of appendiceal mucoceles is surgical resection. The surgical approach depends on the tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM) staging. Importantly, this staging system is distinct from that of colorectal adenocarcinoma.

References:

Leonards LM, Pahwa A, Patel MK, Petersen J, Nguyen MJ, Jude CM. Neoplasms of the Appendix: Pictorial Review with Clinical and Pathologic Correlation. RadioGraphics. 2017;37(4):1059-1083. doi:10.1148/rg.2017160150

Van Hooser A, Williams TR, Myers DT. Mucinous appendiceal neoplasms: pathologic classification, clinical implications, imaging spectrum and mimics. Abdominal Radiology. 2018;43(11):2913-2922. doi:10.1007/s00261-018-1561-9

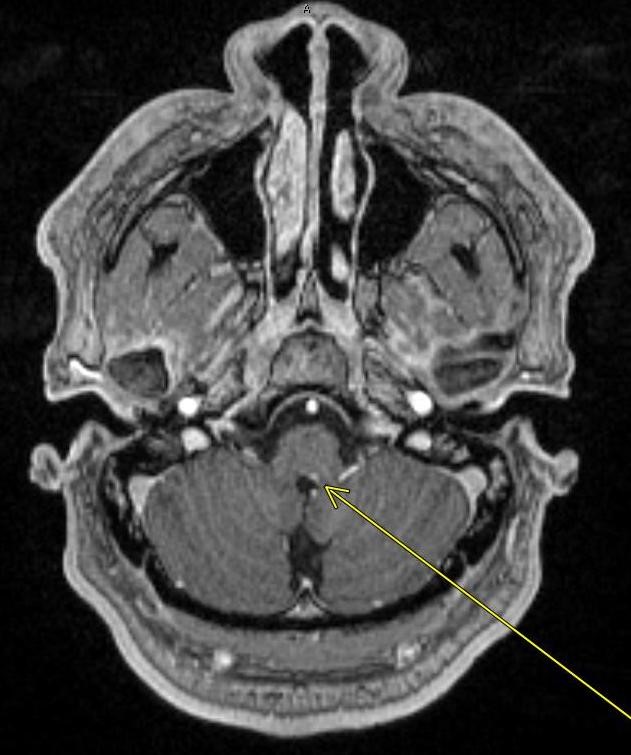

January 2023: Cavernous Malformation with Developmental Venous Anomaly

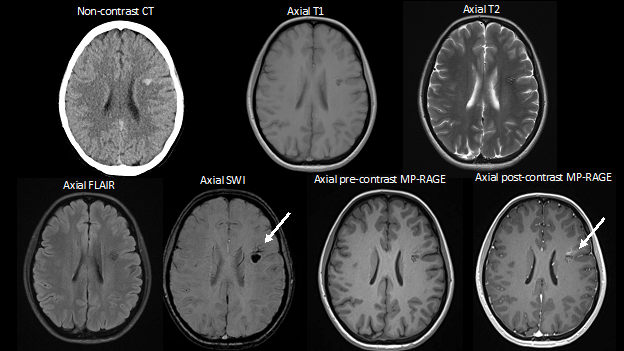

History: A 30-year-old female presented to the primary care physician for headache. Noncontrast CT of the brain was obtained to assess for acute intracranial pathology. CT findings prompted evaluation with an MRI of the brain.

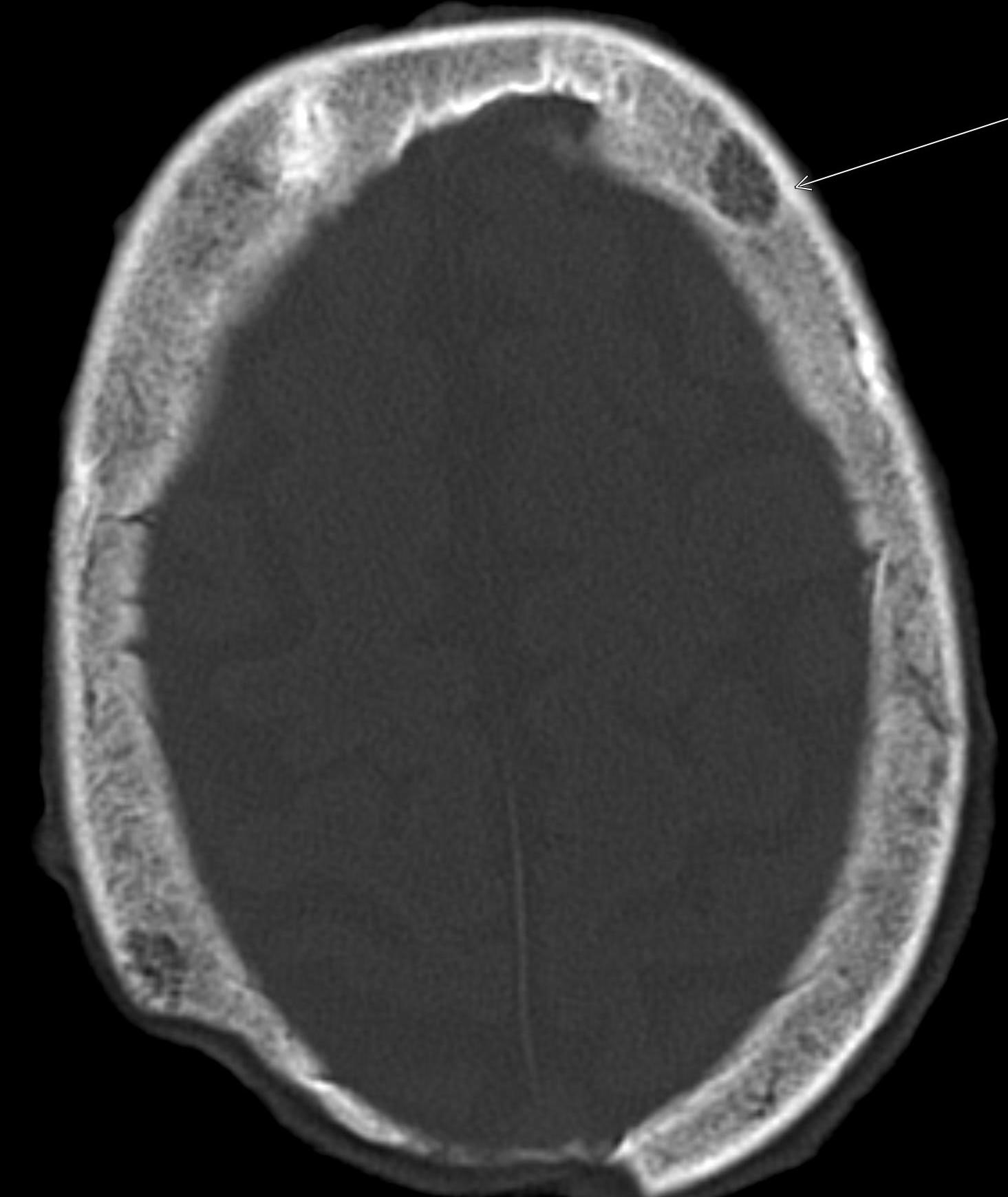

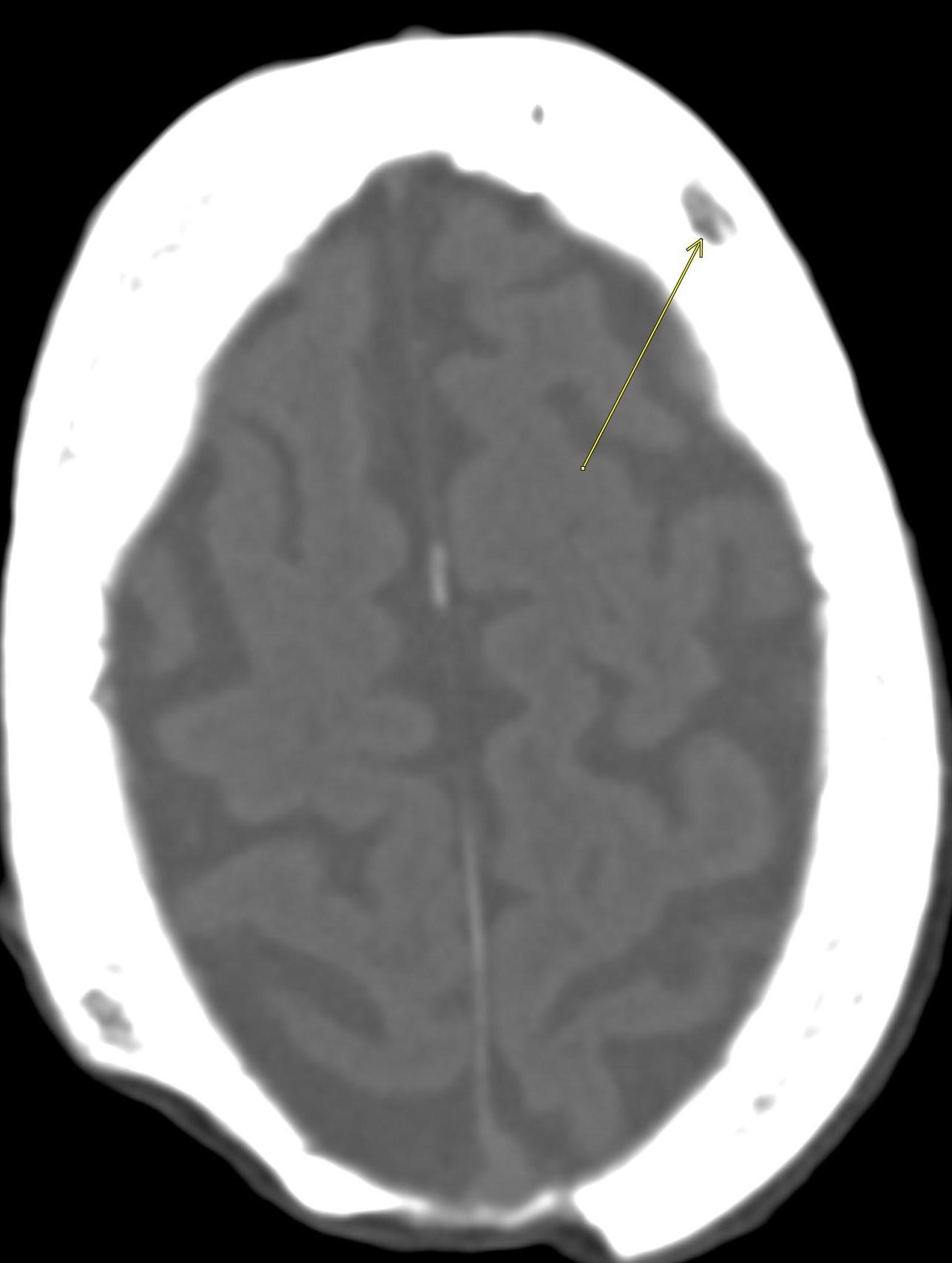

Findings:

Axial non-contrast CT demonstrates a focal area of hyperattenuation in the left corona radiata without significant associated mass effect, findings which raise concern for a small parenchymal hematoma versus cavernous malformation. MRI with and without contrast is thus obtained for further evaluation. Subsequent MRI demonstrates a popcorn-like lesion with mixed T1 and T2 intensity, T2 hypointense hemosiderin rim, and associated gradient susceptibility on SWI centered in the left frontal lobe in the corona radiata, corresponding to the hyperattenuating lesion on CT. FLAIR imaging does not demonstrate any associated edema. There is no finding to suggest recent hemorrhage. On the post-contrast MP-RAGE sequence, there are radially oriented vessels along the anterior aspect of the lesion with associated abnormality on SWI (white arrows).

Diagnosis: Cavernous malformation with developmental venous anomaly

Teaching Points: A cavernous malformation, also known as a cavernoma, is a slow-flow vascular malformation that occurs in the central nervous system. Cavernous malformations are made up of multiple endothelial-lined “caverns.” There is no normal intervening brain tissue. While some patients are asymptomatic, others present with intracranial hemorrhage, headache, seizures, or focal neurological deficits. In about one third of cases, cavernous malformations are associated with developmental venous anomalies (DVA), which are the most common type of intracranial vascular malformation. DVAs drain normal brain parenchyma and are comprised of multiple venules that coalesce into a venous trunk that often ultimately drains into a dural sinus.

Cavernomas are challenging to identify on CT. They are also angiographically occult lesions, although catheter angiography may sometimes identify associated abnormal venous flow. Overall, MRI is the best modality in diagnosing cavernomas. A combination of histopathology and MRI categorize cavernomas into four different types. Type 2 cavernomas are the most common. These lesions have a “popcorn” appearance with heterogeneous T1 and T2 signal and a T2 hypointense rim. The internal signal characteristics are related to different ages of internal thrombosis and loculated hemorrhagic products. The T2 hypointense rim is related to peripheral deposition of hemosiderin after it has been cleared from the center of the lesion. With the exception of hemorrhagic lesions, cavernomas typically do not cause significant mass effect. Surrounding vasogenic edema is usually related to hemorrhage.

T2*-weighted gradient recall echo (GRE) and susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) are important in diagnosis because they not only delineate the cavernoma but also potentially an associated DVA, as in the above case. DVA’s are characterized by a classic “medusa-head” appearance caused by a dominant transcortical venous flow void and multiple associated collecting veins. Contrast-enhanced MRI can also be useful in identifying a DVA associated with a cavernoma, as in the above case.

In most cases of cavernous malformation, there is a single, isolated cavernoma. However, a small number of patients have an inherited genetic disease known as hereditary/familial cerebral cavernous malformations, characterized by multiple cavernomas.

Solitary cavernomas are sometimes surgically resected if they cause seizures or focal neurological deficits, while management of multiple lesions in hereditary cases is more controversial.

References:

Batra S, Lin D, Recinos PF, Zhang J, Rigamonti D. Cavernous malformations: natural history, diagnosis and treatment. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2009;5(12):659-670. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2009.177

Das K, Rangari K, Singh S, Bhaisora K, Jaiswal A, Behari S. Coexistent cerebral cavernous malformation and developmental venous anomaly: Does an aggressive natural history always call for surgical intervention? Asian Journal of Neurosurgery. 2019;14(1):318. doi:10.4103/ajns.ajns_196_18

Flemming KD, Kumar S, Brown RD, Lanzino G. Predictors of Initial Presentation with Hemorrhage in Patients with Cavernous Malformations. World Neurosurgery. 2020;133:e767-e773. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2019.09.161

Kearns KN, Chen CJ, Yagmurlu K, et al. Hemorrhage Risk of Untreated Isolated Cerebral Cavernous Malformations. World Neurosurgery. 2019;131:e557-e561. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2019.07.222

Vilanova JC, Barceló J, Smirniotopoulos JG, et al. Hemangioma from Head to Toe: MR Imaging with Pathologic Correlation. RadioGraphics. 2004;24(2):367-385. doi:10.1148/rg.242035079

Zafar A, Quadri SA, Farooqui M, et al. Familial Cerebral Cavernous Malformations. Stroke. 2019;50(5):1294-1301. doi:10.1161/strokeaha.118.022314

December 2022: Metastatic Pulmonary Calcification

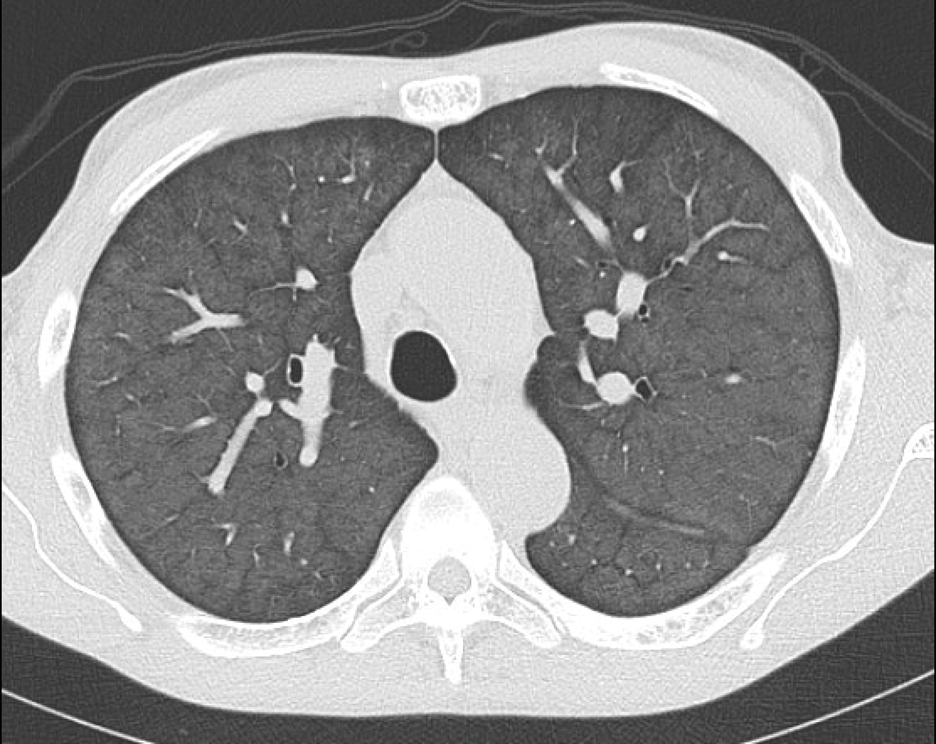

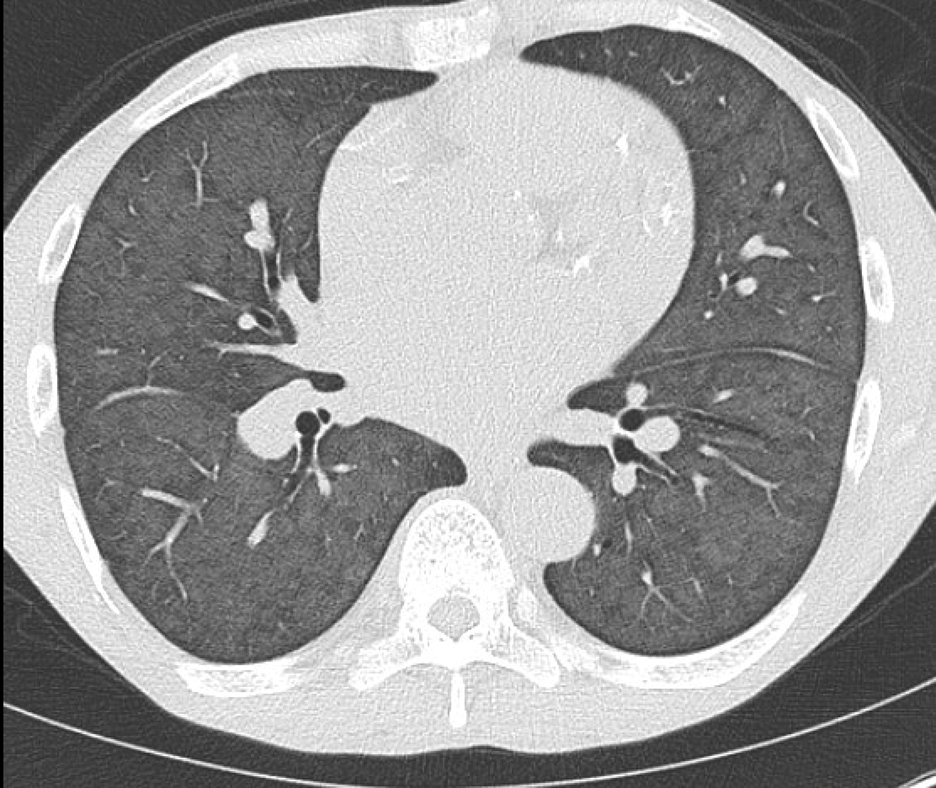

History: A 55-year-old male with end stage renal disease presented for kidney transplant evaluation. Noncontrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained and included portions of the lower chest.

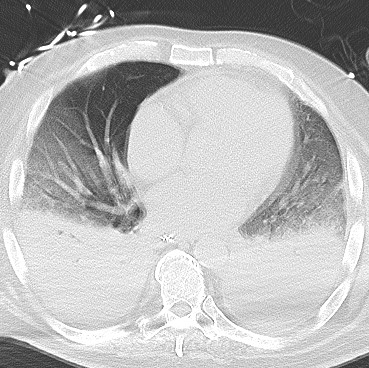

Findings: Axial noncontrast CT of the chest demonstrates diffuse centrilobular groundglass opacities in both lungs with sparing of the pleural surfaces and interlobular septal regions. Note is also made of mild cardiomegaly, aortic valve calcifications, and extensive calcific coronary artery atherosclerosis.

Diagnosis: Metastatic pulmonary calcification

Teaching Points: Metastatic pulmonary calcification (MPC) is a complication of end stage renal disease. It occurs when calcium deposits inside alveolar septa and the walls of small pulmonary vessels and bronchioles. This can be seen in patients with chronic renal failure, primary hyperparathyroidism, and milk-alkali syndrome, amongst other etiologies. Some patients are asymptomatic, while others may develop respiratory failure. MPC usually develops gradually.

Chest radiographs can be normal or depict airspace disease consistent with pneumonia or pulmonary edema. While chest radiographs have very limited sensitivity in demonstrating the calcification associated with MPC, CT proves very useful. One of the most common CT manifestations of MPC is centrilobular ground glass nodular opacities, which frequently contain calcifications. Other manifestations include dense consolidation or solid nodules that may be calcified. An upper lung predominance has been reported. An important associated finding of MPC includes vessel calcification in the chest wall.

Differential diagnostic considerations may include alveolar microlithiasis, infections such as tuberculosis, silicosis, coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, and talcosis.

Although MPC usually does not require intervention, phosphate and calcium normalization are usually targeted. In MPC related to chronic renal failure, parathyroidectomy, renal transplant, or dialysis may prove beneficial.

References:

Belém LC, Souza CA, Souza Jr. AS, et al. Metastatic pulmonary calcification: high-resolution computed tomography findings in 23 cases. Radiologia Brasileira. 2017;50(4):231-236. doi:10.1590/0100-3984.2016-0123

Belém LC, Zanetti G, Souza AS, et al. Metastatic pulmonary calcification: State-of-the-art review focused on imaging findings. Respiratory Medicine. 2014;108(5):668-676. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2014.01.012

Chung MJ, Lee KS, Franquet T, Müller NL, Han J, Kwon OJ. Metabolic lung disease: imaging and histopathologic findings. European Journal of Radiology. 2005;54(2):233-245. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2004.07.003

Hartman TE, Müller NL, Primack SL, et al. Metastatic pulmonary calcification in patients with hypercalcemia: findings on chest radiographs and CT scans. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1994;162(4):799-802. doi:10.2214/ajr.162.4.8140993

November 2022: Osteoid Osteoma

History: A 12-year-old male presented to his primary care office with right leg pain for a few weeks. Further workup was performed, including radiographs of the right femur followed by an MRI of the pelvis.

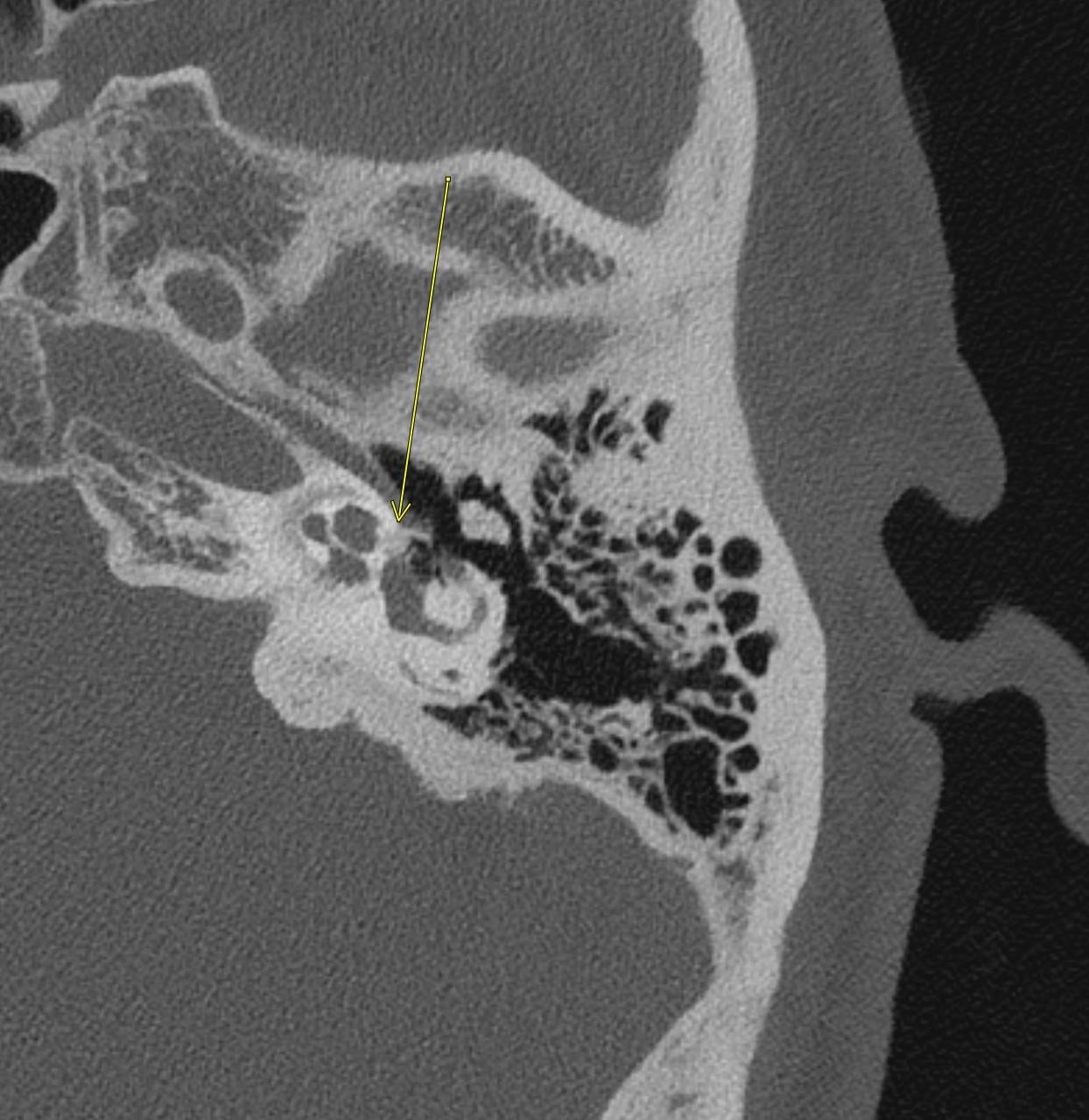

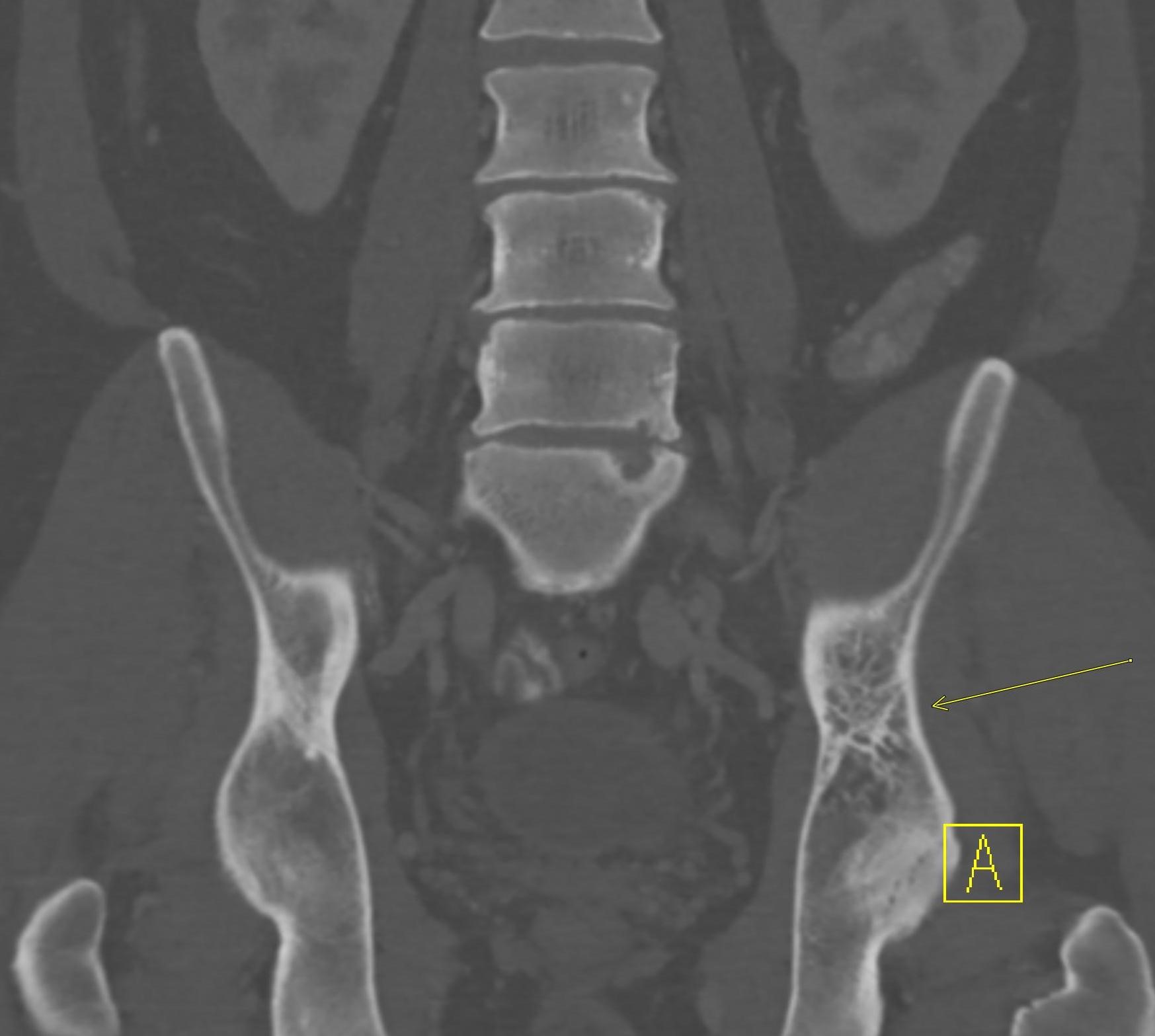

Findings:

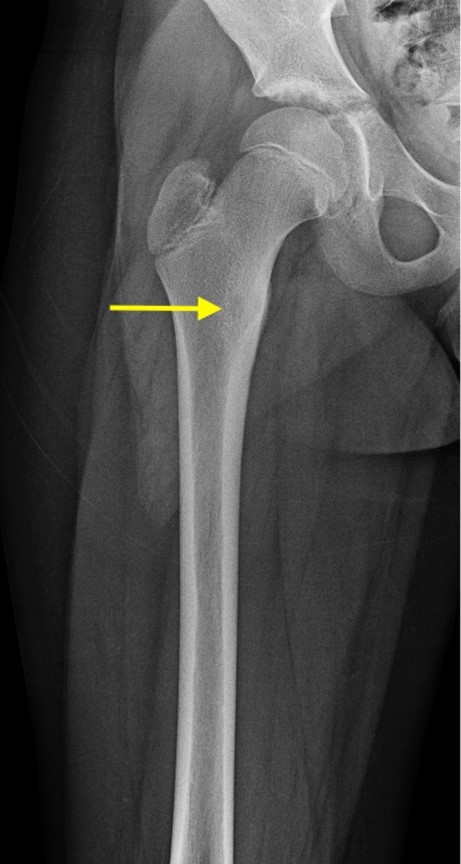

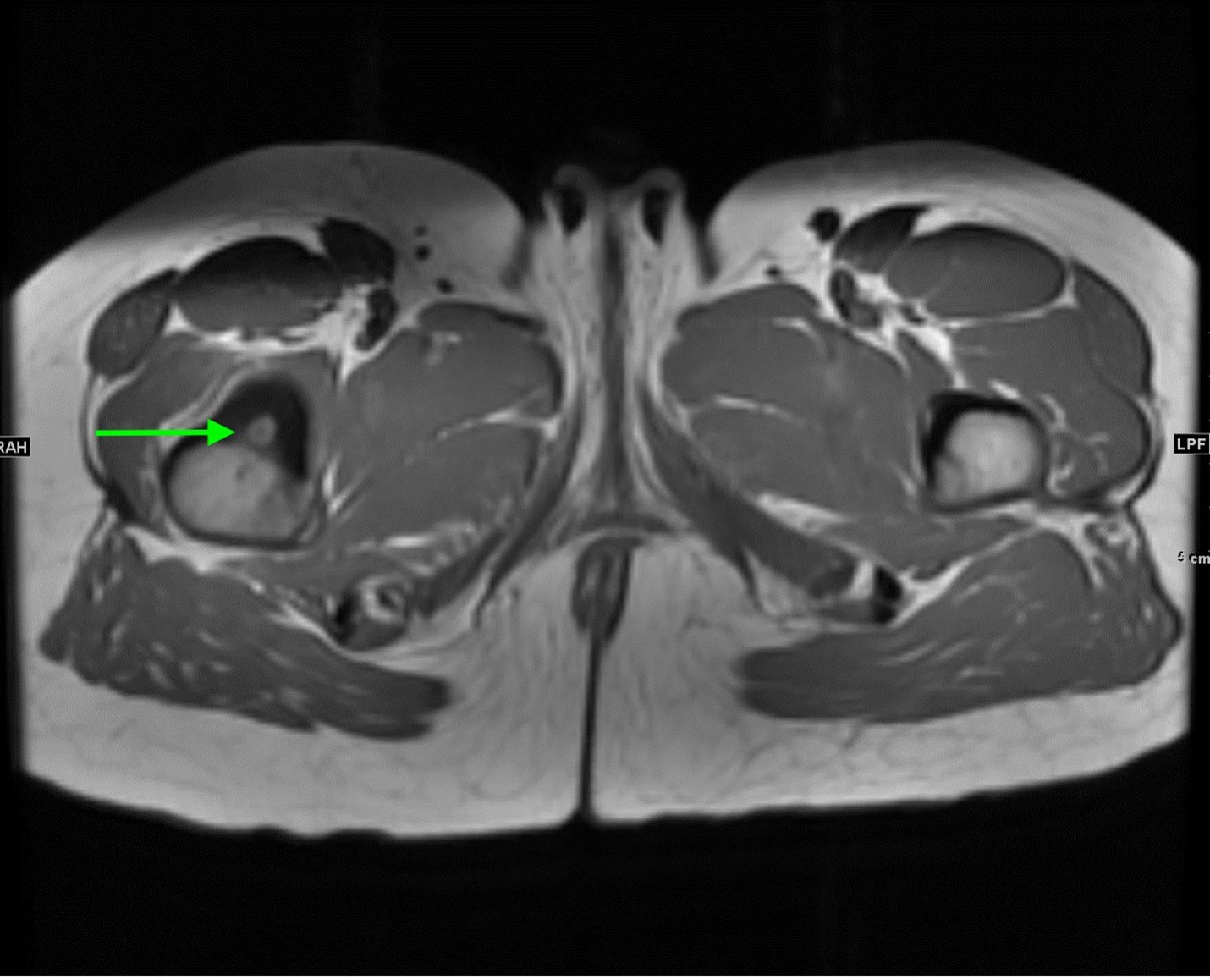

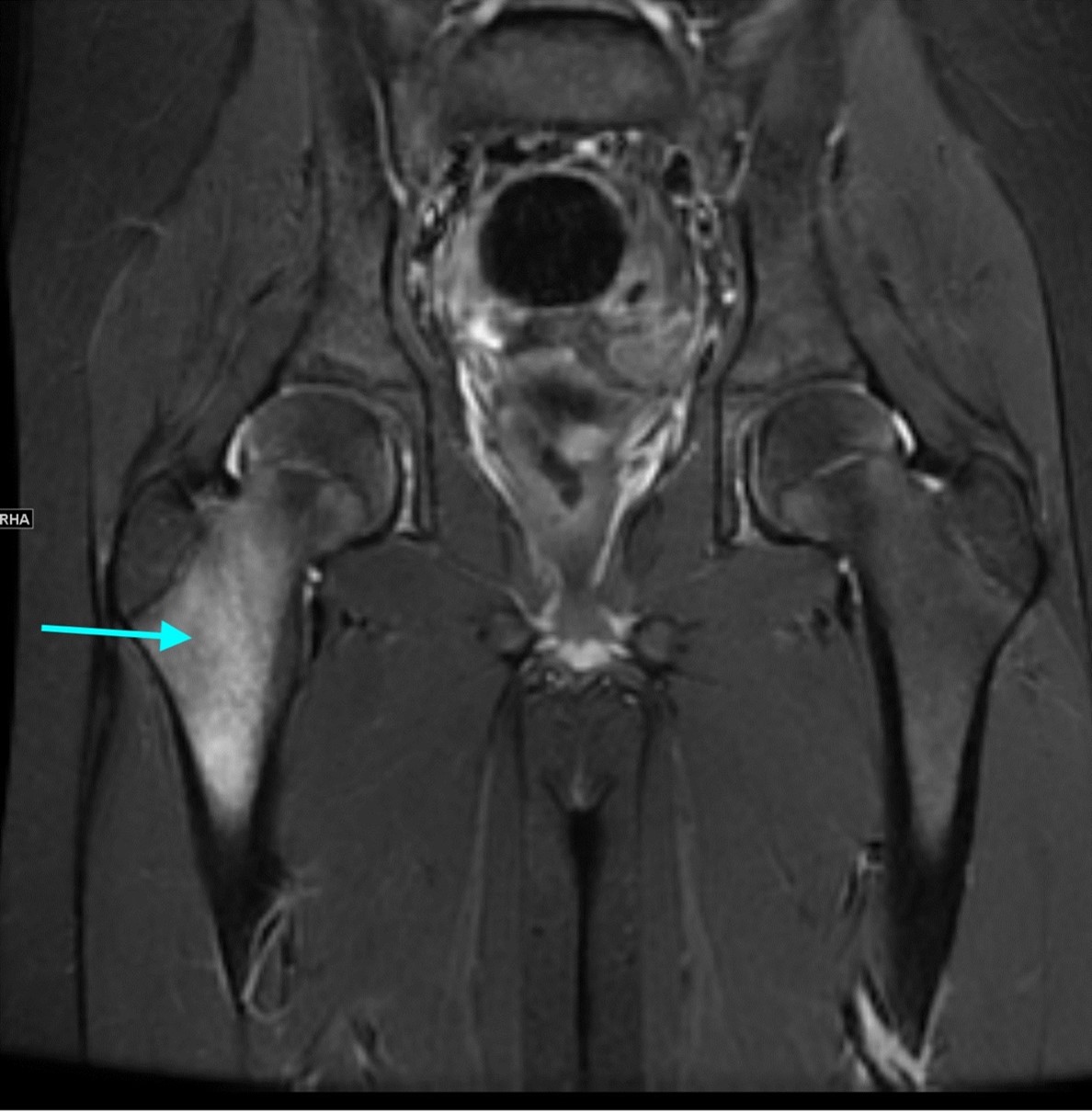

AP radiograph of the right femur shows mild sclerosis of the medial proximal femur with a subtle central lucent nidus (yellow arrow). No acute fracture is identified.

Axial and coronal T1 weighted images of the pelvis demonstrate a targetoid nidus with central T1 hypointensity compatible with calcification centered in the medial proximal right femur (green arrows). There is moderate cortical thickening surrounding the lesion. There is no evidence for fracture.

Coronal STIR images of the pelvis show extensive edema within the bone marrow surrounding the nidus extending from the proximal metaphysis to the proximal diaphysis of the right femur (teal arrow).

Diagnosis: Osteoid osteoma

Teaching Points: Osteoid osteomas are benign skeletal lesions characterized by a nidus of osteoid tissue associated with cortical thickening, marrow edema, and sclerosis. They have a predilection for males ranging from 7 to 25 years of age. Classically, patients complain of nighttime pain that is relieved by NSAIDS/aspirin. Symptoms often occur over weeks to years before patients present to a clinician.

One of the classification schemes for osteoid osteomas divides lesions into the following categories: subperiosteal, intracortical, endosteal, and intramedullary. Osteoid osteomas can occur in almost any bone, although they are most commonly found in the long bones (particularly femur and tibia).

On radiographs, osteoid osteomas are characterized by a round/oval nidus measuring less than 2 cm that demonstrates varying degrees of calcification. There may be associated cortical thickening and sclerosis. The sensitivity of radiographs largely depends on the location of the lesion. For example, cortical lesions will often have a radiolucent nidus with surrounding sclerosis, whereas intramedullary lesions demonstrate almost no sclerosis.

CT is excellent for identifying the nidus when radiographs are not revealing. It also appears to be superior to MRI in identifying the nidus. On CT, there is a low attenuation round/oval nidus that sometimes has high attenuation internally related to mineralization. Varying degrees of sclerosis are associated with the nidus.

On MRI, there is low/intermediate signal intensity on T1 weighted images and low to high signal intensity on T2 weighted images corresponding to different degrees of mineralization in the nidus. Sometimes, this may result in a target-like appearance. There is associated marrow edema. Effusions may be seen in the joints and soft tissues.

Important differential considerations for osteoid osteoma include stress fractures, intracortical abscess, osteoblastoma, and compensatory hypertrophy of the contralateral pedicle with unilateral spondylolysis, amongst others.

Some patients and clinicians may prefer conservative, noninterventional management for osteoid osteomas. Interventional management options include en bloc surgical resection of the osteoid osteoma nidus and image guided approaches including cryoablation, radiofrequency ablation, trephine excision, or laser thermocoagulation.

References:

Chai JW, Hong SH, Choi JY, et al. Radiologic Diagnosis of Osteoid Osteoma: From Simple to Challenging Findings. RadioGraphics. 2010;30(3):737-749. doi:10.1148/rg.303095120

Greenspan A. Benign bone-forming lesions: osteoma, osteoid osteoma, and osteoblastoma. Skeletal Radiology. 1993;22(7). doi:10.1007/bf00209095

Noordin S, Allana S, Hilal K, et al. Osteoid osteoma: Contemporary management. Orthopedic Reviews. 2018;10(3). doi:10.4081/or.2018.7496

Radcliffe SN, Walsh HJ, Carty H. Osteoid osteoma: the difficult diagnosis. European Journal of Radiology. 1998;28(1):67-79. doi:10.1016/s0720-048x(97)00071-5

October 2022: Acute Perforated Diverticulitis

History: An 80-year-old male presented to the Emergency Department with abdominal pain. A contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained for further evaluation.

Findings:

Axial and coronal CT images of the abdomen/pelvis in soft tissue window demonstrate colonic diverticulosis with marked bowel wall thickening and perifascial thickening and surrounding fat stranding (yellow arrows). No definite intramural abscess is seen. There is no drainable fluid collection.

Sagittal CT image of the abdomen/pelvis in lung window demonstrates foci of free air in portions of the abdomen (red arrow).

Diagnosis: Acute perforated diverticulitis

Teaching Points: Diverticulitis refers to the acute inflammation of colon diverticula. Colonic diverticula likely form due to degeneration of the colonic mucosa and local increases in pressure, most commonly in the sigmoid colon. Eighty percent of patients develop diverticulosis by the age of 80; diverticulitis affects 10-25% of patients with diverticulosis. It is believed that diverticulosis progresses to diverticulitis in the context of fecal stasis when a fecalith becomes lodged within a diverticular neck. Diverticulitis can be complicated by perforation, peritonitis, abscess formation, and fistulae amongst other issues. Patients with diverticulitis typically present with left-sided abdominal pain, low grade fevers, and alterations of bowel movements.

Given the nonspecific nature of presenting symptoms, imaging plays an important role in confirming the diagnosis of diverticulitis. CT is highly sensitive and specific in diagnosis. It also demonstrates the extent of disease, ultimately guiding management. Previously, barium enema was used for diagnostic purposes but has been overwhelmingly replaced by CT. Ultrasound, while highly sensitive and specific, depends largely on sonographer expertise and is typically pursued when there is a contraindication to CT. MRI, while also highly sensitive and specific, has not been thoroughly studied and is not widely used.

Findings consistent with diverticulitis on CT include colonic wall thickening along with pericolic fat stranding and hyperemia. Eventually, there is associated thickening of retroperitoneal/peritoneal folds. Phlegmons can be identified as small enhancing masses near the site of inflammation. Abscesses are usually characterized by thick, hyperdense walls with internal hypodensity.

Perforation can be diagnosed when there are foci of extraluminal gas, best demonstrated on lung or bone windows, or in the presence of extraluminal contrast. During supine CT exams, free air is typically identified in nondependent portions of the abdomen. Sometimes, focal bowel wall discontinuity can be identified to suggest perforation.

The major differential consideration for colonic diverticulitis is perforated colon cancer. Colon cancer may be differentiated from diverticulitis by the presence of eccentric wall thickening and associated lymphadenopathy. However, colonoscopy should be performed in cases of uncomplicated diverticulitis when there are concerning CT features or in accordance with national screening guidelines. Colonoscopy should be performed in all cases of complicated diverticulitis.

Uncomplicated diverticulitis can typically be managed on an outpatient basis. For complicated cases, many patients can be managed nonoperatively with bowel rest and IV antibiotics with some abscesses benefiting from percutaneous drainage. For those patients who do not respond to nonoperative management, the typical course includes a Hartmann procedure or primary anastomosis with or without diversion.

References: You H, Sweeny A, Cooper ML, Von Papen M, Innes J. The management of diverticulitis: a review of the guidelines. Medical Journal of Australia. 2019;211(9):421-427. doi:10.5694/mja2.5027610.

Sessa B, Galluzzo M, Ianniello S, Pinto A, Trinci M, Miele V. Acute Perforated Diverticulitis: Assessment With Multidetector Computed Tomography. Seminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI. 2016;37(1):37-48. doi:10.1053/j.sult.2015.10.003

Shin D, Rahimi H, Haroon S, et al. Imaging of Gastrointestinal Tract Perforation. Radiologic Clinics of North America. 2020;58(1):19-44. doi:10.1016/j.rcl.2019.08.004

September 2022: Dural Venous Sinus Thrombosis

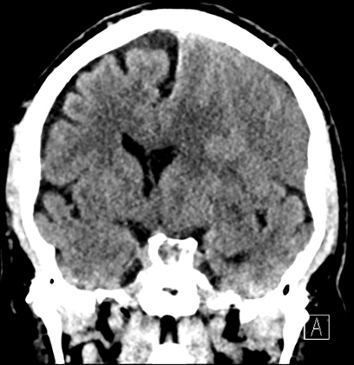

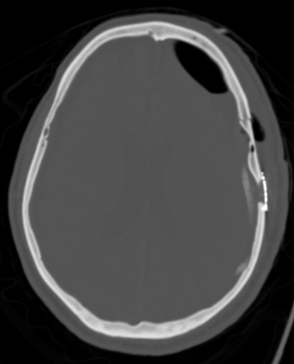

History: A 60-year-old female presented to the Emergency Department with an ongoing headache for a few days. A non-contrast CT of the head was obtained for further evaluation.

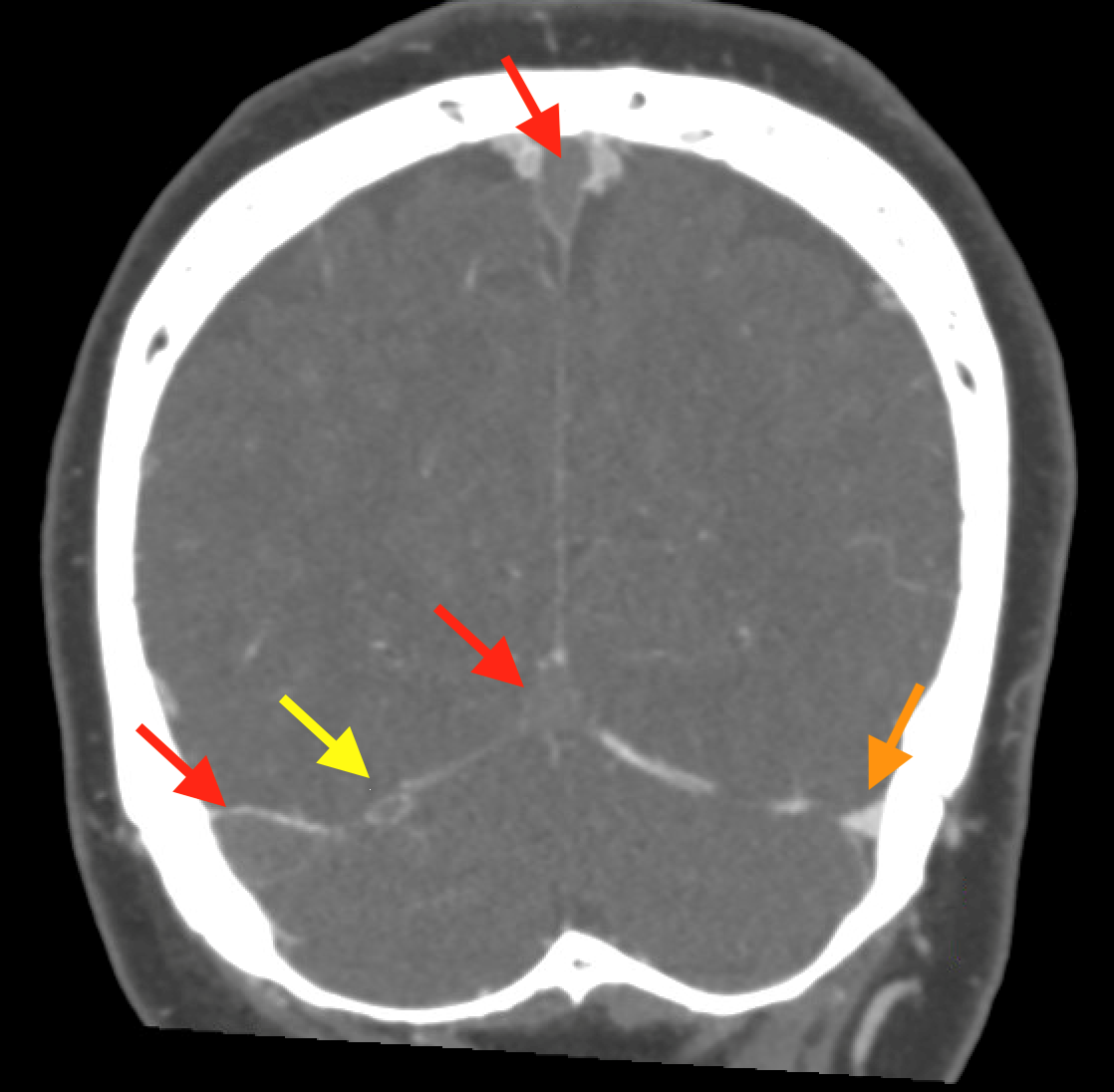

Findings:

Coronal non-contrast CT of the head (shown above) demonstrates hyperdensity and expansion of the right transverse sinus with additional hyperdensity in the posterior half of the straight sinus and posterior third of the superior sagittal sinus (blue arrows). The left transverse sinus is comparatively lower in density (purple arrow). Additional areas of hyperdensity and expansion are noted in the torcula, right sigmoid sinus, and right jugular bulb (not shown). These findings are consistent with dural venous sinus thrombosis in the areas of hyperattenuation. A focal curvilinear hyperdensity along the right tentorial leaflet is suspicious for subdural hemorrhage or a thrombosed vein (green arrow). CT venogram was obtained to further investigate these findings.

Coronal and sagittal images from the CT venogram (shown below) demonstrate complete lack of opacification of the right transverse sinus, posterior half of the straight sinus, and posterior third of the superior sagittal sinus with partial filling defect in the mid third of the superior sagittal sinus. The left transverse sinus opacifies with contrast (orange arrow). Additional areas of complete non-opacification are noted in the torcula, right sigmoid sinus, right jugular bulb with partial filling defect in the right upper jugular vein (not shown).

The filling defects on the CT venogram correspond to areas of hyperdensity on the non-contrast exam, consistent with occlusive thrombosis of the right transverse sinus, sigmoid sinus, jugular bulb, torcula, posterior half of the straight sinus, and posterior third of the superior sagittal sinus with subocclusive thrombus in the mid third of the superior sagittal sinus and right upper jugular vein. Associated thrombosis is noted in a superficial vein along the right tentorial leaflet, corresponding to the curvilinear hyperdensity in this location on the non-contrast exam (yellow arrow).

Diagnosis: Dural venous sinus thrombosis

Teaching Points: Dural venous sinus thrombosis refers to the thrombotic occlusion of the intracranial dural sinuses. The dural venous sinuses are vascular structures located between the periosteal and meningeal layers of the dura and receive blood from throughout the brain. Risk factors for dural venous sinus thrombosis include pregnancy, oral contraceptives, mastoiditis or similar conditions, inherited prothrombotic states, malignancy, and myeloproliferative disorders amongst others. Patient presentation is typically delayed from onset of symptoms. Most commonly, patients present with acute headache.

Initial evaluation at the time of presentation usually includes non-contrast enhanced CT of the brain. On non-contrast enhanced CT, acute thrombosis is signaled by increased attenuation within the sinuses. As clot retracts, the concentration of red blood cells and hemoglobin increases, resulting in higher attenuation of the thrombus, usually around 60-90 Hounsfield Units. Elevated hemoglobin levels and polycythemia vera have been found to cause false positive results on non-contrast enhanced CT due to the intrinsic high attenuation of blood in these cases.

CT venography can be used to further evaluate for dural venous sinus thrombosis. During this procedure, contrast is injected and images are acquired after a fixed delay at which contrast is expected to opacify the relevant vessels. Any filling defects are suggestive of thrombosis.

Conventional MRI can be used to evaluate dural venous sinus thrombosis and demonstrates different appearances on T1-weighted imaging and T2-weighted/FLAIR imaging based on the characteristics of hemoglobin degradation. Gradient echo and susceptibility weighted sequences demonstrate blooming artifact during certain stages of thrombus evolution. MR venography is also useful in evaluating dural venous sinus thrombosis and can be performed with or without contrast.

Possible long-term complication of dural venous sinus thrombosis include dural arteriovenous fistulas and idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Treatment of this entity revolves around the initiation of anticoagulation.

References:

Buyck PJ ., De Keyzer F, Vanneste D, Wilms G, Thijs V, Demaerel P. CT Density Measurement and H:H Ratio Are Useful in Diagnosing Acute Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2013;34(8):1568-1572. doi:10.3174/ajnr.a3469

Ghoneim A, Straiton J, Pollard C, Macdonald K, Jampana R. Imaging of cerebral venous thrombosis. Clinical Radiology. 2020;75(4):254-264. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2019.12.009

August 2022: Small Bowel Obstruction Due to Spigelian Hernia

History: A 70-year-old female presented to the Emergency Department with left lower quadrant abdominal pain and several episodes of emesis. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis was ordered for further evaluation.

Findings:

Axial and coronal images of the abdomen/pelvis demonstrate numerous loops of mildly dilated small bowel with fecalization of the small bowel contents (red arrows). There is a spigelian hernia in the left lower abdominal wall (yellow arrows). A transition point is identified in the distal ileum within the spigelian hernia (yellow arrows). The bowel loop entering the spigelian hernia is mildly dilated, the loop within the hernia is normal in caliber, while the exiting loop is collapsed. There is nonspecific thickening of the terminal ileum distal to the obstruction. A small amount of fluid is noted in the spigelian hernia sac, and there is a moderate amount of edema adjacent to the dilated loops of bowel.

Diagnosis: Small Bowel Obstruction Due to Spigelian Hernia

Teaching points: A spigelian hernia is a type of anterior abdominal wall hernia that occurs through the spigelian fascia, which is an aponeurosis between the rectus abdominis muscle and the semilunar line. Spigelian hernias often occur at or below the arcuate line, as there is no posterior rectus sheath at that level. They are also known as lateral ventral hernias.

Overall, spigelian hernias are rare, comprising 1-2% of all abdominal wall hernias. Most often, spigelian hernias are acquired, although children may present with congenital spigelian hernias. Risk factors for acquired spigelian hernias include but are not limited to morbid obesity, multiple pregnancies, COPD, and rapid weight loss. Spigelian hernias are usually small and high risk for strangulation.

Diagnosis of spigelian hernias can be quite challenging. Patients may present with nonspecific pain when they have a reducible hernia. Others present with a complication of the hernia, such as small bowel obstruction. Physical exam is usually not reliable in the diagnosis. The diagnosis is typically made on CT, which also allows physicians to determine the contents, location, and possible complications of the hernia.

On CT, a spigelian hernia is diagnosed when there is a fascial defect in the appropriate location, as described above. The hernia may contain fat, omentum, small bowel, and/or large bowel. Small bowel obstruction, when present, is diagnosed based on the presence of dilated proximal bowel and collapsed distal bowel with an intervening transition point.

Because of the high risk for strangulation, spigelian hernias are treated surgically. Open and laparoscopic techniques are used, with laparoscopic techniques demonstrating improved morbidity compared to open techniques.

References:

Harrison LA, Keesling CA, Martin NL, Lee KR, Wetzel LH. Abdominal wall hernias: review of herniography and correlation with cross-sectional imaging. RadioGraphics. 1995;15(2):315-332. doi:10.1148/radiographics.15.2.7761638

Martin M, Paquette B, Badet N, Sheppard F, Aubry S, Delabrousse E. Spigelian hernia: CT findings and clinical relevance. Abdominal Imaging. 2012;38(2):260-264. doi:10.1007/s00261-012-9889-z

Mustaffa N, Leong R, Katelaris P. Gastrointestinal: Spigelian hernia; an uncommon cause of longstanding intermittent abdominal pain. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2012;28(1):202-202. doi:10.1111/jgh.12027

Salameh JR. Primary and Unusual Abdominal Wall Hernias. Surgical Clinics of North America. 2008;88(1):45-60. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2007.10.004

July 2022: Emphysematous Cystitis

History: A 55-year-old female presented to the Emergency Department with hematuria. The patient was status post renal transplant two months prior to presentation. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis was ordered to evaluate for stones in the urinary tract.

Findings:

Axial and coronal images of the abdomen/pelvis demonstrate extensive submucosal and intraluminal air within the bladder (red arrows). Some of the air extends into the right lower quadrant renal allograft collecting system (yellow arrows). An Incidental note is made of hepatic steatosis. The native kidneys are atrophic.

Diagnosis: Emphysematous cystitis

Teaching points: Emphysematous cystitis is an infection of the bladder due to gas-forming bacteria, most commonly Escherichia coli and Enterobacter aerogenes. Important risk factors include diabetes, immunocompromised state, and neurogenic bladder. In diabetics, poor glycolysis within tissues results in excessive interstitial glucose, which is then fermented by certain bacteria, producing gas. Women are affected more than men. Patients may present with dysuria, increased urinary frequency, and/or hematuria. While some patients are asymptomatic, others can present with sepsis/septic shock. Emphysematous cystitis may be present alongside emphysematous pyelitis and emphysematous pyelonephritis.

CT is very sensitive for the detection of emphysematous cystitis and demonstrates intraluminal and intramural gas within the bladder. Radiographs may demonstrate curvilinear/mottled lucent areas in profile with the bladder. On radiographs, the appearance of emphysematous cystitis can mimic other entities such as emphysematous vaginitis or gas gangrene of the uterus. Ultrasound frequently shows mural thickening and increased echogenicity of the bladder, sometimes with foci of dirty shadowing. Noninfectious etiologies of intra-vesicular gas must be considered, including trauma, instrumentation, or fistulas with adjacent organs (specifically vesicovaginal or vesicocolic fistulas). CT cystography may be useful for identifying vesicocolic fistulas.

Treatment of emphysematous cystitis includes antibiotics, hyperglycemic control, and appropriate urinary drainage. If there is concomitant bladder outlet obstruction, this should be corrected.

References:

Grayson DE, Abbott RM, Levy AD, Sherman PM. Emphysematous Infections of the Abdomen and Pelvis: A Pictorial Review. RadioGraphics. 2002;22(3):543-561. doi:10.1148/radiographics.22.3.g02ma06543

Joseph RC, Amendola MA, Artze ME, et al. Genitourinary tract gas: imaging evaluation. RadioGraphics. 1996;16(2):295-308. doi:10.1148/radiographics.16.2.8966288

Ranjan SK, Navriya SC, Kumar S, Mittal A, Bhirud DP. Emphysematous cystitis: A case report and literature review of 113 cases. Urology Annals. 2021;13(3):312-315. doi:10.4103/UA.UA_61_20

Yu M, Robinson K, Siegel C, Menias C. Complicated Genitourinary Tract Infections and Mimics. Current Problems in Diagnostic Radiology. 2017;46(1):74-83. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2016.02.004

May 23, 2022: Fallopian Tube Torsion

History: A 35-year-old female presented to the Emergency Department with right lower quadrant pain for 1 day. CT of the abdomen and pelvis was ordered due to concern for appendicitis.

Findings:

The coronal CT image of the abdomen and pelvis shows a large 9.0 cm simple-appearing right adnexal cyst.

Axial and coronal CT images of the abdomen and pelvis show a dilated, tubular, fluid-filled structure along the periphery of the right ovary with a beaked appearance, most consistent with a dilated fallopian tube. There is associated thickening and enhancement of the fallopian tube wall. The right ovary itself is slightly enlarged.

Diagnosis: Fallopian Tube Torsion

Teaching Points:

Fallopian tube torsion is a type of adnexal torsion and usually occurs in the setting of coexisting ovarian torsion, although isolated tubal torsion can occur. Twisting of the ovary and/or fallopian tube around its vascular pedicle (in the suspensory ligament) results in vascular compromise and potentially ovarian infarction. Initially, the ovarian vein and lymphatics are affected and result in engorgement and enlargement of the ovary. Eventually, if not treated quickly, the ovarian artery becomes compressed and results in ischemia/infarction. Complications of isolated fallopian tube torsion include fallopian tube necrosis or gangrenous transformation. Risk factors for tubal torsion include ovarian or paraovarian masses (especially if greater than 5 cm), adhesions, tubal ligation, pelvic inflammatory disease, and hydro/hematosalpinx. Interestingly, tubal torsion usually occurs on the right. Most patients present with severe acute abdominal pain and vomiting.

On CT, the typical findings suggestive of tubal torsion include an adnexal mass (such as the large adnexal cyst in our case shown above), and a dilated fallopian tube measuring greater than 15 mm in diameter, and associated thickening and enhancement of the fallopian tube wall. Often, the dilated fallopian tube takes on a “beaked” appearance where it tapers toward either end, similar to that seen in closed-loop bowel obstruction. Occasionally, there may also be intraluminal hyperdense material compatible with hemorrhage, not seen in our case. Secondary signs include free pelvic fluid, adjacent fat stranding, and thickening of the broad ligament. On ultrasound, there will be similar findings including a dilated fallopian tube with a thick, echogenic wall and internal debris. Twisting of the vascular pedicle is a specific finding though is not always seen.

If associated with ovarian torsion, as is usually the case, the ovary will be significantly enlarged. Due to the increase in size, the ovary does not have enough space in its usual location within the pelvis and migrates superiorly and anteriorly toward the midline, often positioned in front of the uterus. The uterus has then deviated toward the side of the affected ovary. It is important to remember that normal arterial waveforms within the ovary do not exclude the possibility of torsion, since arterial perfusion is maintained until late in the course of torsion.

Differential considerations based on the imaging appearance of a dilated fluid-filled structure include hydrosalpinx, hematosalpinx, and pyosalpinx. Early tubo-ovarian abscesses could also have a similar appearance.

Treatment is surgical detorsion. In addition, cystectomy is performed for benign lesions and salpingo-oopherectomy is often performed if there is concern for malignancy.

References:

- Dawood MT, et al. Adnexal Torsion: Review of Radiologic Appearances. Radiographics. 2021; 41(2).

- Gross M, et al. Isolated Fallopian Tube Torsion: A Rare Twist on a Common Theme. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2005; 185(6).

- Lourenco A, et al. Ovarian and tubal torsion: imaging findings on the US, CT, and MRI. Emergency Radiology. 2014; 21(2).

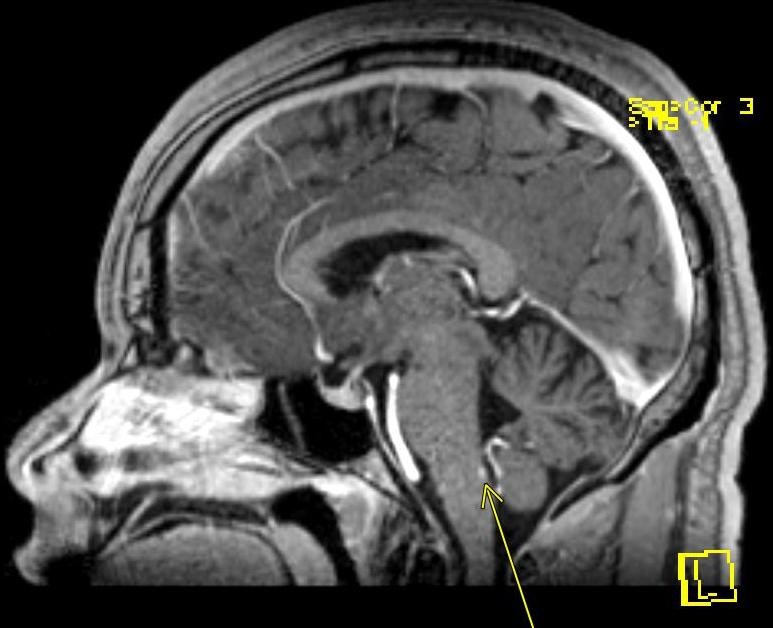

May 16, 2022: Transient Global Amnesia

History: A 50-year-old woman presented to the Emergency Department complaining of memory loss and “mental fog” since waking up that morning. Brain MRI was performed for further evaluation.

Findings:

Axial diffusion-weighted MR image of the brain demonstrates a punctate focus of diffusion restriction in the right hippocampus. There was a corresponding low-intensity signal on ADC images (not shown).

The remainder of the brain was unremarkable. No significant FLAIR signal hyperintensity was seen to suggest a background of microvascular ischemic disease.

Diagnosis: Transient Global Amnesia

Teaching Points:

Transient global amnesia is a rare clinical syndrome in which a patient experiences anterograde and partial retrograde short-term memory loss over a time period of less than 24 hours. Symptoms are transient and usually completely resolve within a few hours, and there are no other associated neurological symptoms. Long-term memory is usually preserved. The exact cause is unknown, but precipitating factors can include emotional/physical stress or pain.